Old Sun Classroom

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

Read moreThe First Floor/Basement of Old Sun Community College (OSCC). Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions. Labels on the Point Cloud indicate past room functions during Old Sun’s time as a residential school. Significant rooms include the boys’ and girls’ playrooms, dining room, kitchen

The first floor of Old Sun served multiple purposes during the building’s operation as a residential school. When not attending classes or performing chores, boys and girls were separated along gender lines. Throughout much of Old Sun’s history, the boys’ playroom was located on the south side of the building, while the girls’ rooms were on the north side. Each playroom had an adjacent washroom which featured a central row of sinks and open showers. Some younger children found the presence of older students in these spaces somewhat intimidating – especially when bathing/washing.

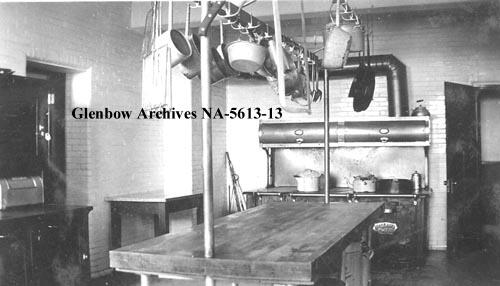

The dining area was centrally located between the playrooms and now serves as the cafeteria for Old Sun Community College. As with the playrooms, boys and girls sat on the east and west sides of the room, respectively, while staff ate in a separate dining area. Students at the school were required to help with cooking, cleaning, and other chores. Survivors’ recounted that serving staff members was a desirable job because students could sneak scraps of the better quality food enjoyed by school employees. In contrast, residential school children would be served foods such as lumpy porridge, oftentimes with soured powdered milk, and be made to take spoonful’s of cod liver oil as well as pills of unknown substances.

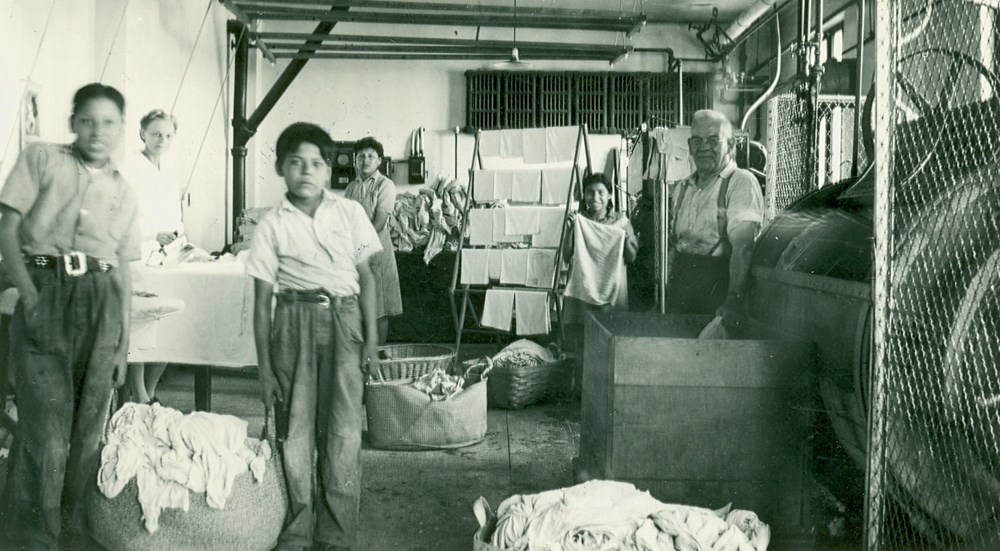

The first floor also contained the various utility rooms for the school. The hallway behind the dining room led to the kitchen, laundry rooms, and the boiler room where students worked cleaning dishes, doing laundry, and shoveling coal.

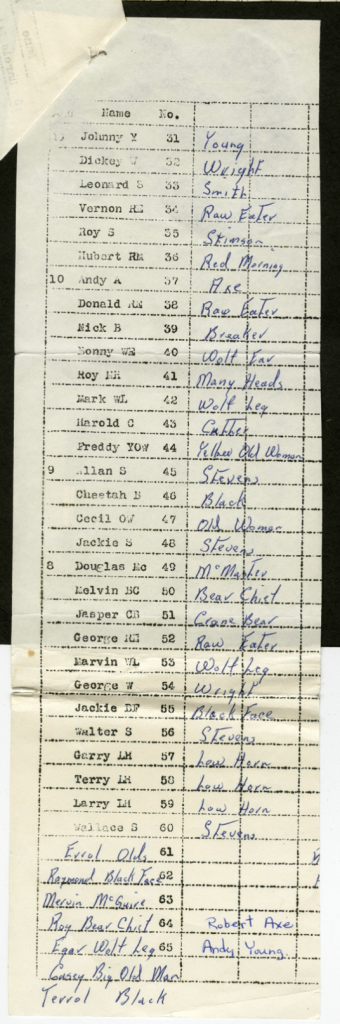

The girls playroom was originally painted a pinkish color with concrete floors. Former student Angeline Ayoungman remembers that when a bathroom pipe was fixed the concrete used to repair the affected area was a different color than the rest of the plain concrete floor. Since the children had no toys, they used this discolored patch to stage games upon. Children would also occasionally steal items like scraps of paper and hair pins to use as makeshift toys.

Survivors have recounted that they never truly “played” the way children normally do. This was because the Blackfoot language spoken by newly arriving students was forbidden in the school. As a result, many children found it difficult to connect and play with each other as they feared punishment for accidentally speaking their language. School intercoms provided an effective means of surveillance. As survivor Allan Stevens described, “there was an intercom, it was connected to the principle’s office.. so he knew when [they] spoke Blackfoot and would call that person to go upstairs and [they] would be strapped.” It is therefore understandable that enjoying recreational time would have been difficult.

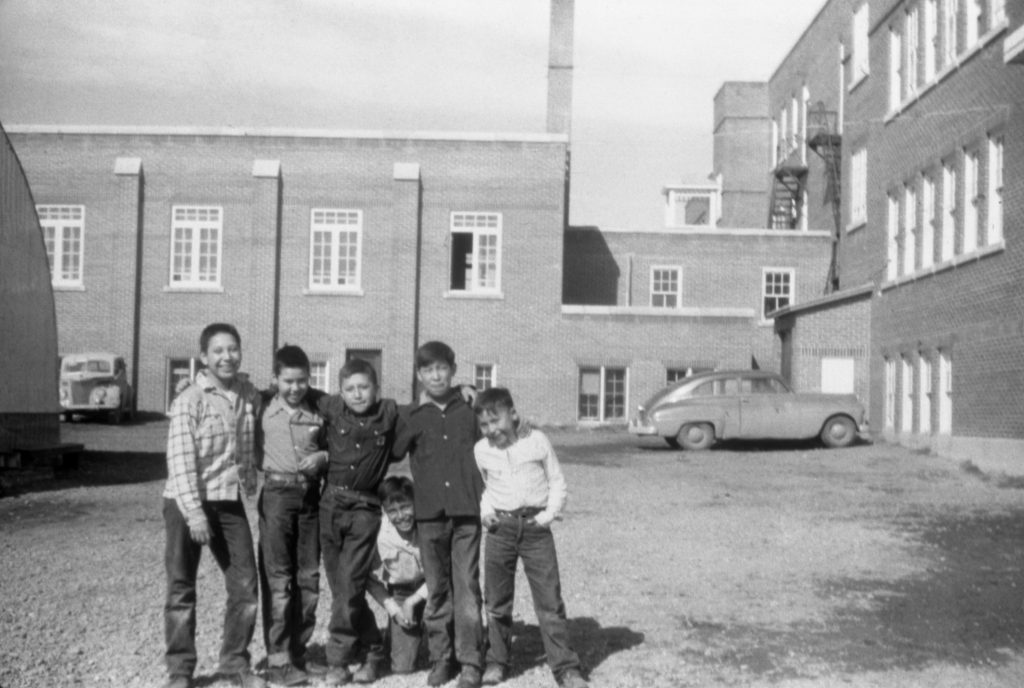

The boys’ playroom was a plain, open space with a communal washroom and shower on the west side – making it a mirror image of the girl’s playroom. The bathroom was a large undivided room featuring a row of sinks. A communal shower located directly across from the toilers containing six shower heads. Aside from a single toilet and sink off the dormitories, these were the only facilities available to the large number of students attending the school. Play was limited as students were not given toys or games. Bullying was also prevalent among students at the school. Growing up in the abusive environment of the residential school, some students learned these types of behaviours. This not only contributed to the intergenerational trauma Indigenous communities still suffer today, but also to high rates of mistreatment, bullying, and abuse between students themselves. The rigorous separation of gender and age within the schools contributed to the divides between students.

Adjacent to the playroom was the washroom. The bathrooms featured communal sinks and showers. When students would come to IRS as small children it was common practice for them to be washed by a staff member, often using harsh soaps and chemicals, and have their hair cut. Survivors remember having coal oil and powder put in their hair which would sting and hurt. To this day, many former students are unaware of the products that were used. As most students were unfamiliar with showers and had been bathed by family members at home, this was a traumatic and jarring experience. Sometimes students would be made to wash themselves in the sinks instead of showers. The floors were also slippery, and this would lead to falls occasionally resulting in serious injuries.

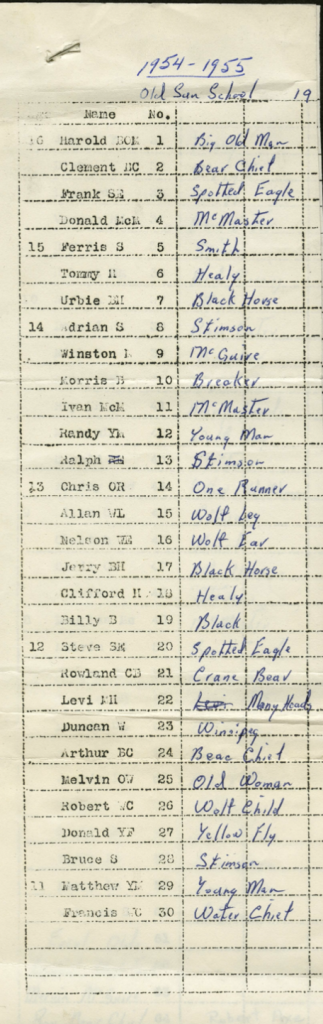

When students arrived they were also assigned numbers. Students were referred to by their number, rather than their name. Corresponding hooks in the bathroom marked where students kept their toothbrushes, and in the cupboards in the dormitories the clothes students wore from home were kept in numbered bags.

Unsanitary conditions existed at the original Old Sun school building in 1907 and continued to plague the new school that served as its replacement in the late 1920’s. In fact, sanitary conditions were so bad at the old building that calls were made by noted residential school whistle blower Dr. Peter H Bryce to tear the building down in 1907. He noted that privies (outhouses) were located between 50 and 150 ft from the main building and that the surrounding grounds were prone to flooding which resulted in the contamination of six wells. It is therefore not surprising that many students were constantly sick.

Problems continued after the construction of the replacement brick building. During the schools first year, Indian Agents reported leaky toilets and bathtubs, sinks falling off walls, and water tanks not properly releasing water. Throughout the 1940’s, basins and toilets were continually clogged, leading to strong odours cited as being “beyond description” (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6351, Reel C-8707). Pools of water caused by pipe blockages due to roof drainage issues were also observed in the boy’s playroom and washroom, resulting in unsanitary conditions. An engineer brought in to assess the situation later that year declared that the entire sewage system would need to be overhauled to address the issue.

The Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) inaction in addressing various building issues directly impacted the experiences of school children attending residential schools. Infrastructure was often left unfinished or incomplete for long periods of time. Seven years after the Edmonton Indian Residential School opened, seating had yet to be installed, forcing students to sit on washbasin stands to rest. At Old Sun, plaster fell from the walls and ceilings of the boy’s playroom as repeated requests for bricking or cementing were ignored. Requests for basic items such as toothbrushes and bedding were also regularly denied by the DIA. Schools that were in the public eye, however, were often granted requests for items like new mattresses as government officials believed it was important that the DIA be seen in a positive light.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel to different areas of the first floor/basement by clicking on the floating arrows.

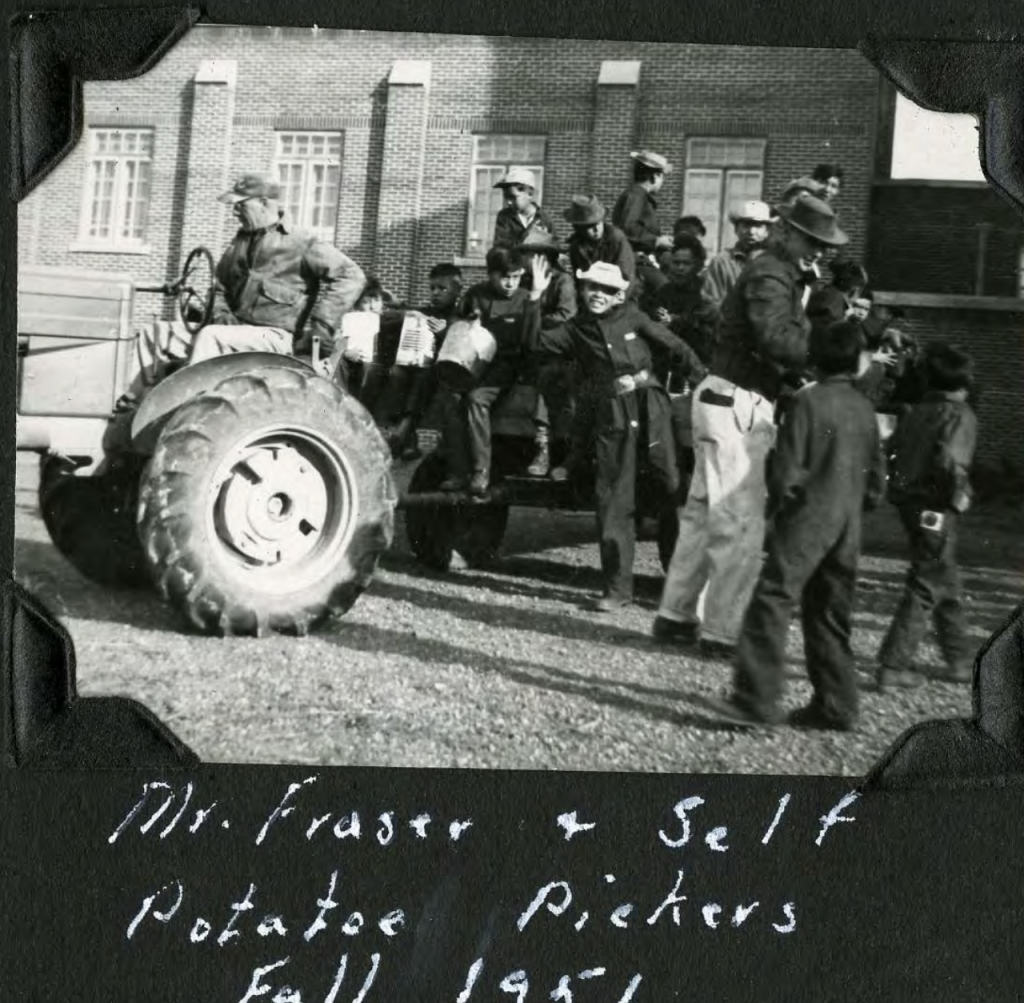

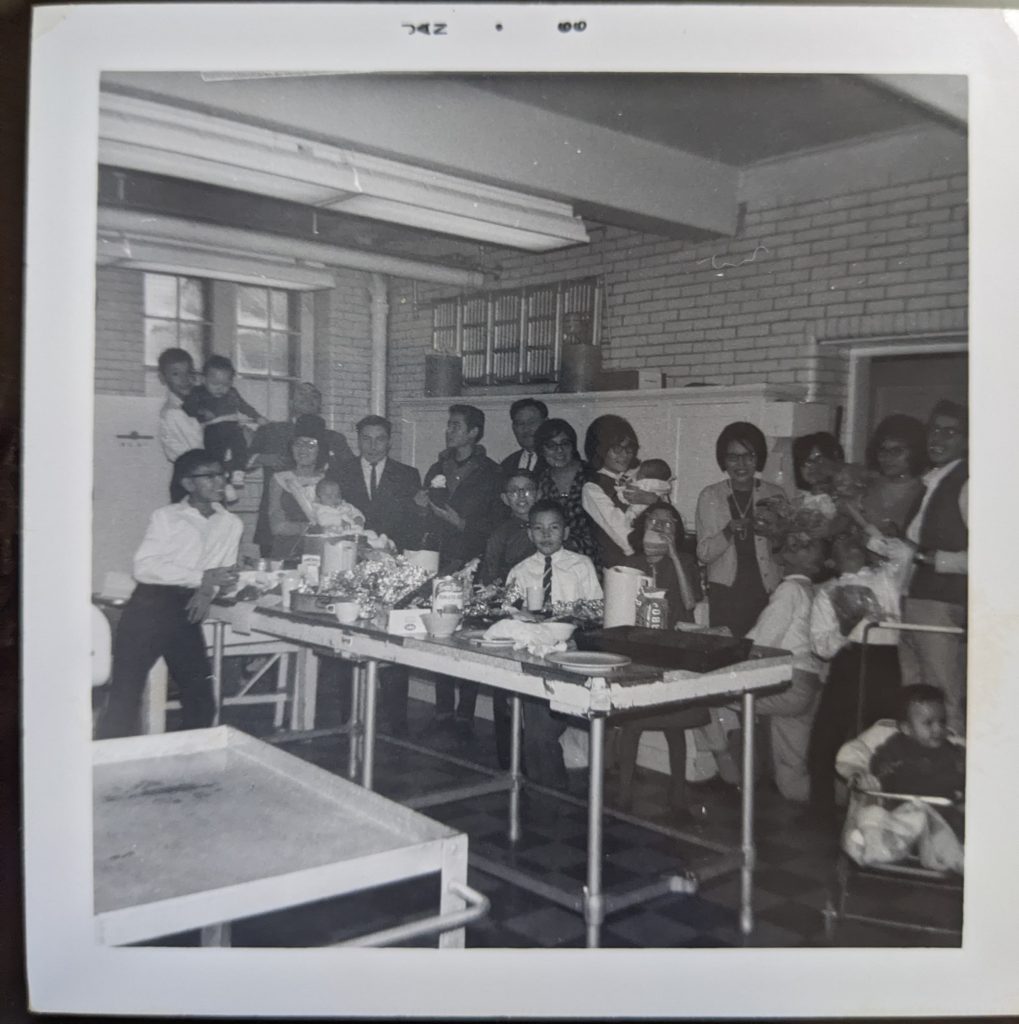

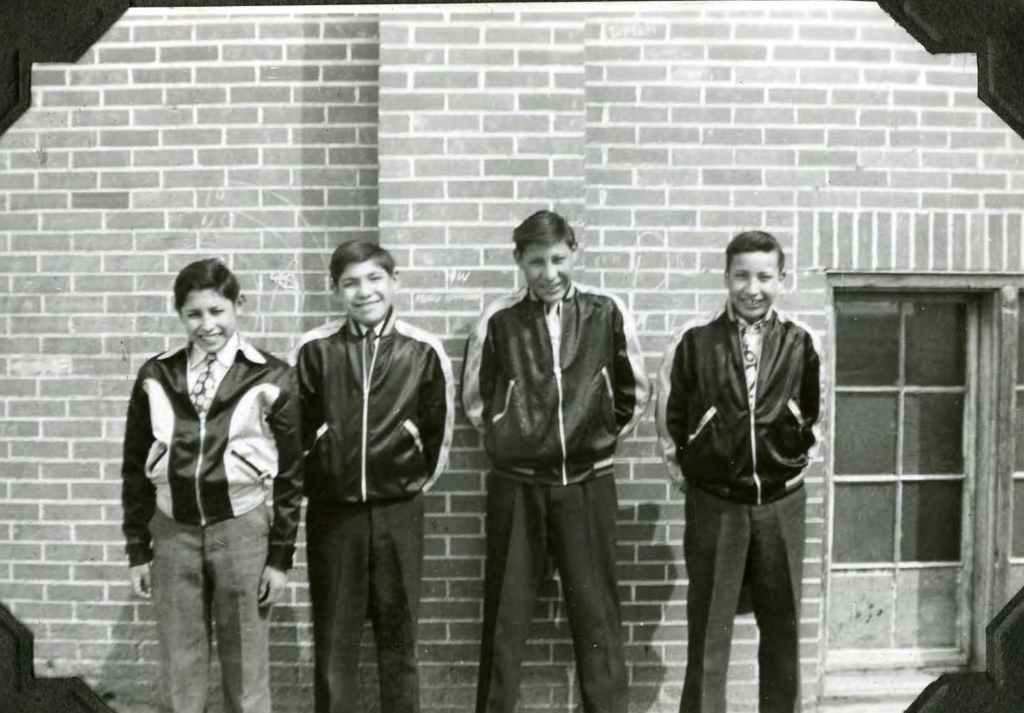

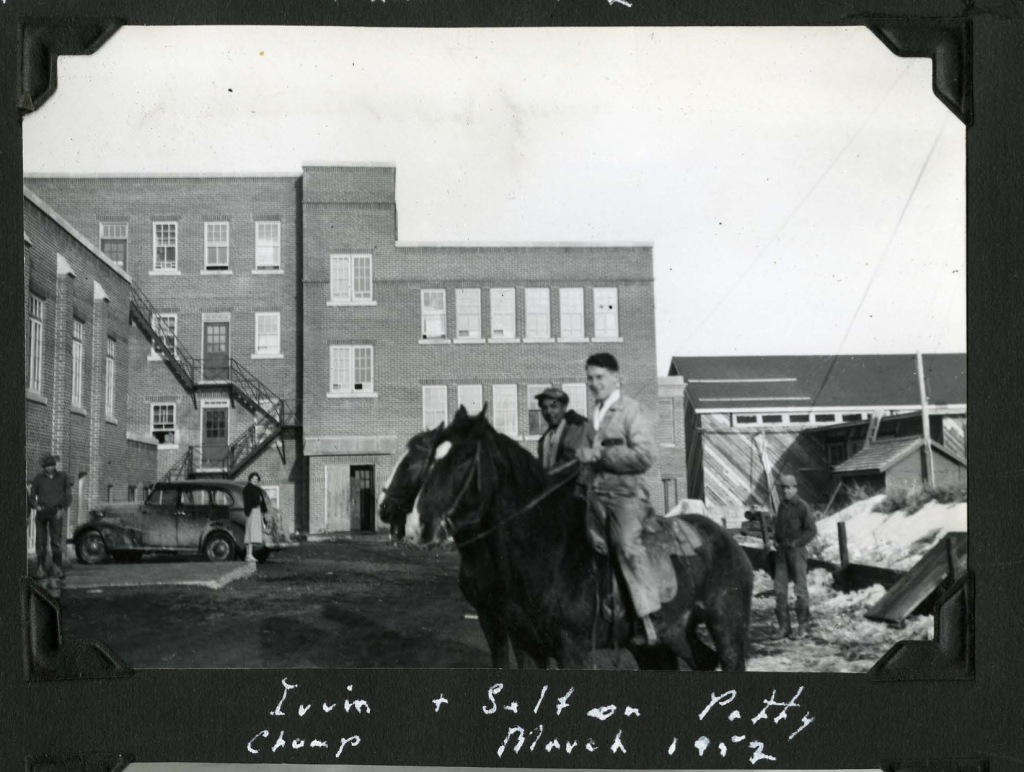

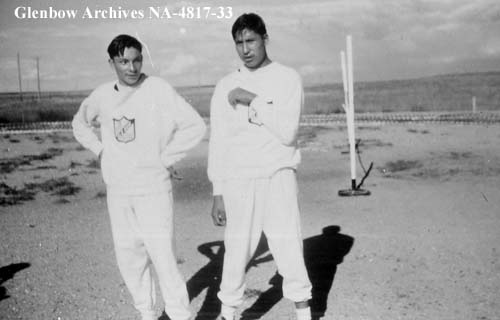

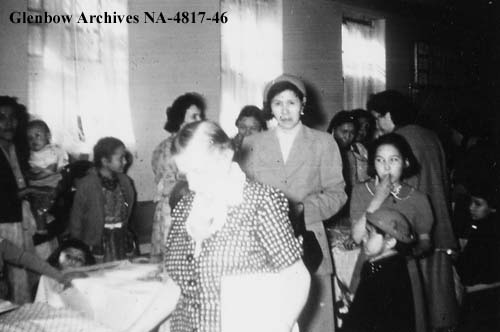

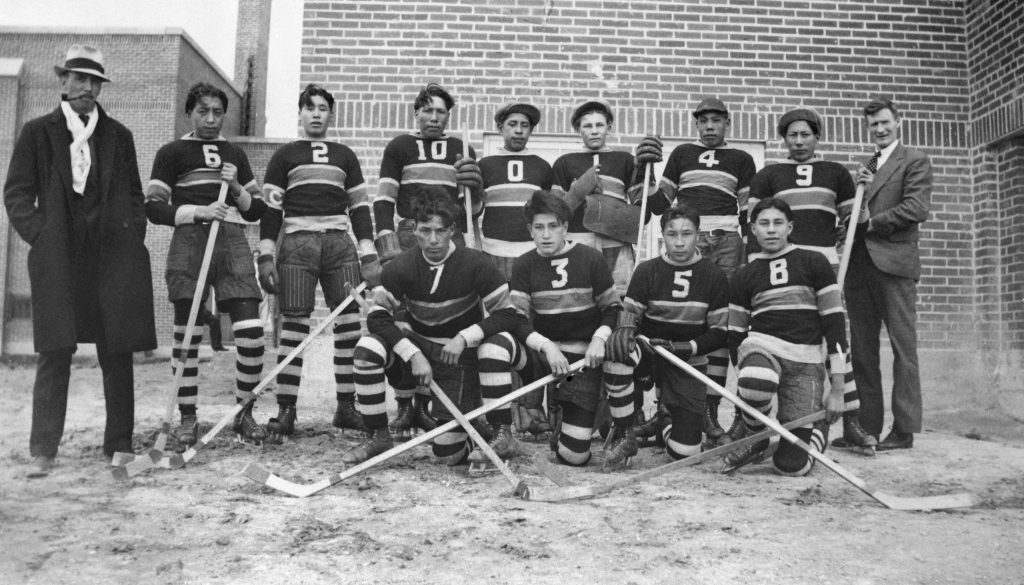

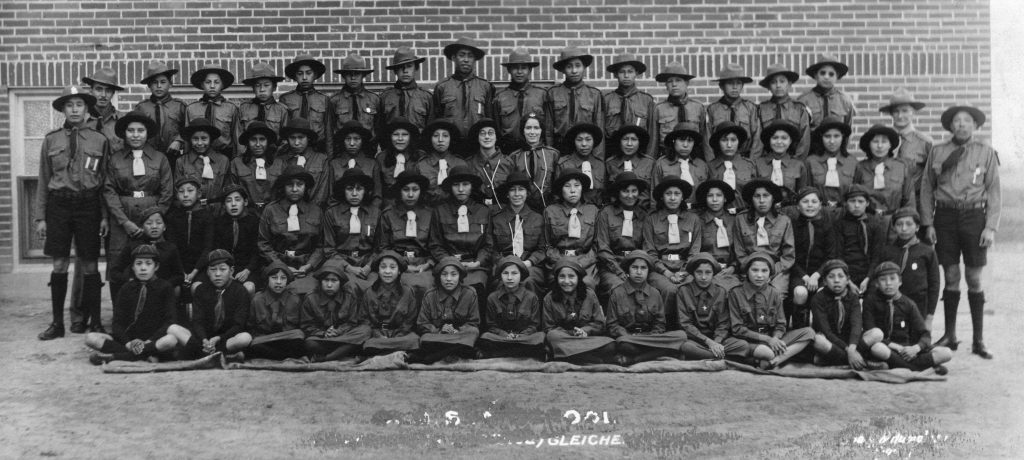

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos of Old Sun's 1st floor. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the first floor of Old Sun that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alta. - Boys at morning wash up. - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-191 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/P75-103-S7-191-585x1024.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alta. - Girls' sopball team. - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-202 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-202.jpeg)

![Old Sun Residential School, Gleichen, Alta. - Wash up time for boys. - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-203 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-203.jpeg)

![(written on back of photo P75-103-S7-203). Wash up time for boys. - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-203A from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-203A.jpeg)

![Old Sun Residential School, Gleichen, Alta. - Principal the Rev. E.S.W. Cole and Confirmation Class. Photo taken in student dining room - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-207 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-207.jpeg)

![The Wedding Breakfast. Head table at the reception for wedding of Alieen Ayoungman (former student) and Horace Gladstone taken in the student dining area- [195-?]. P7538-1001 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1001.jpeg)

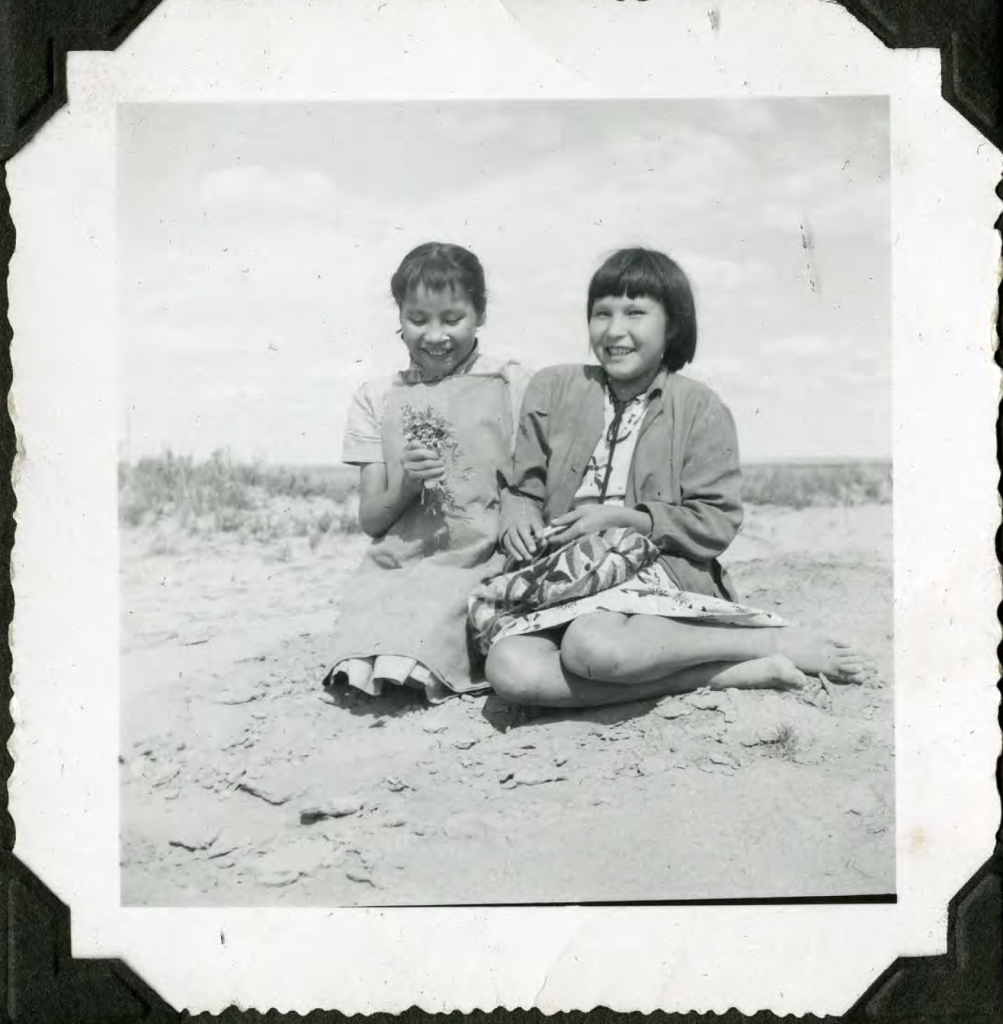

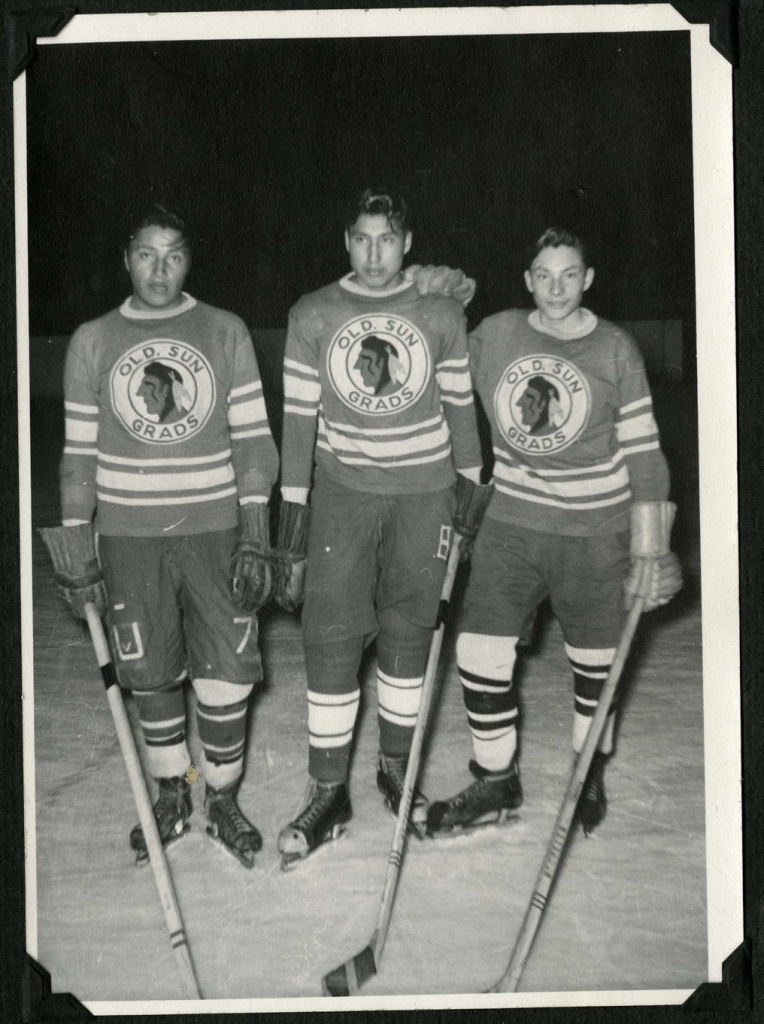

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta - Children skating. - [ca. 1945]. P7538-1008 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1008.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta - Girls' sports team and coaches, taken in student dining room - [194-?]. P7538-1012 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1012.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta - Girls' sports team and coaches, taken in student dining room - [194-?]. P7538-1013 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1013.jpeg)

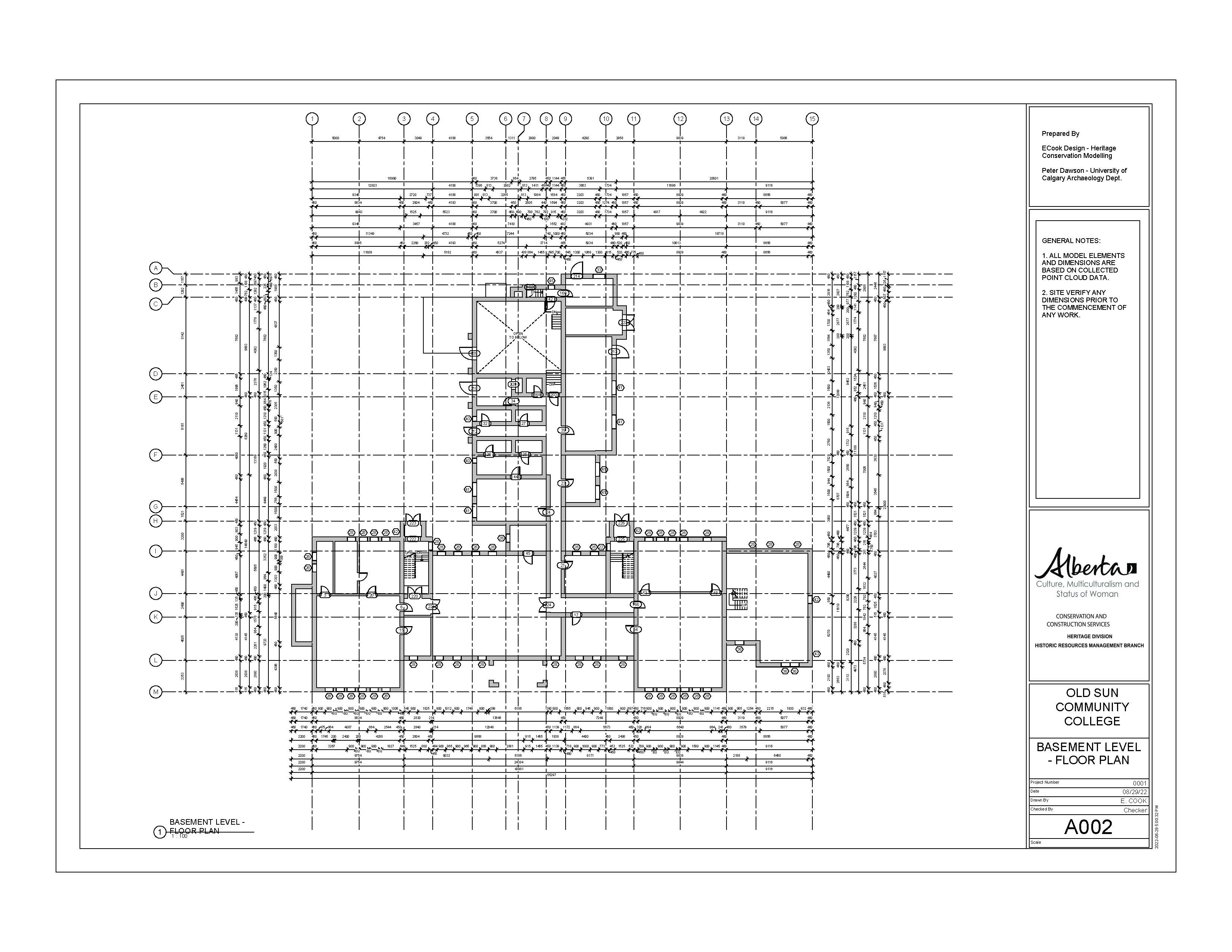

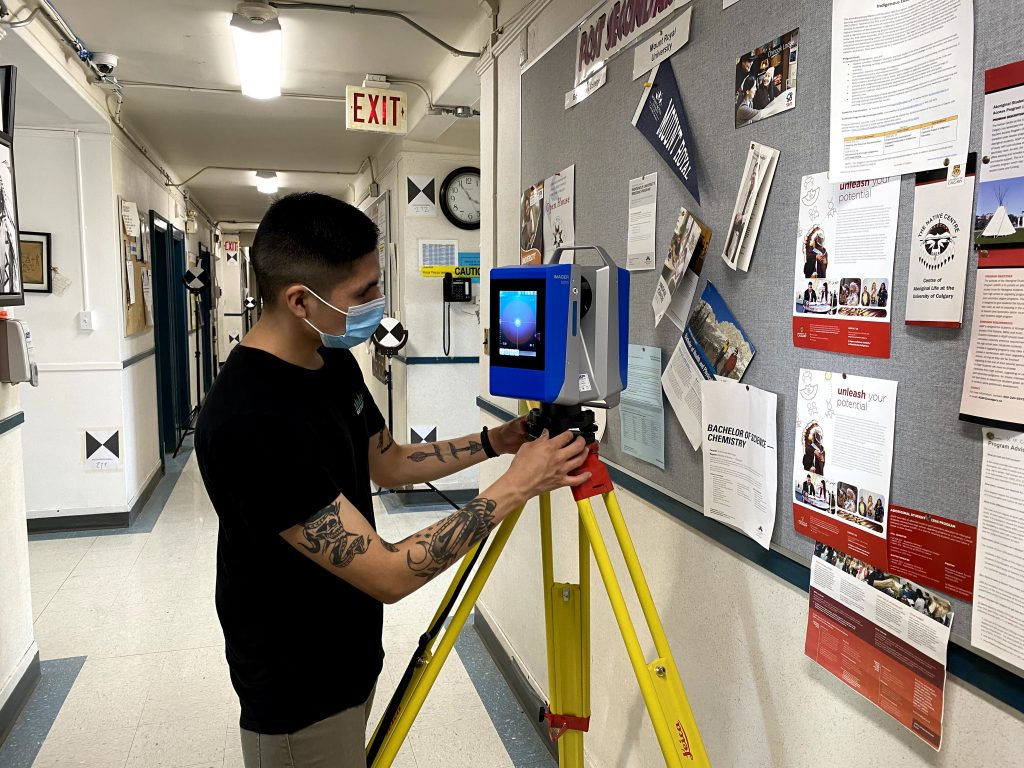

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee.

Some of the threats faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans contained in this archive, which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. There were three specific areas that placed the health and safety of students at great risk: Fire Hazards and Protection Measures; Water Quality, and Sanitation and Hygiene. As you explore the archive, you will find more information about the nature of these hazards and their impact on students.

Boilers and the Risk of Fire

Archival documents reveal that fires were common at all three of the schools preserved in this archive. Many of these fires originated in basement boiler rooms where coal was burned to heat water as part of the hydronic heating systems used by each school. Other high-risk locations included kitchens and laundry areas.

Old Sun Indian Residential School suffered its first fire within a year of its completion (1931). A fire caused by a defective heating element in one of the boilers had resulted from a small explosion. Investigators noted that the boilers in the basement of Old Sun were unmonitored at the time of the incident, suggesting that it could have been prevented. A second incident involving boilers occurred in 1947, and resulted in an extended holiday break for students as repairs had to be undertaken to restore heat and hot water to the building. Rather than address the recurring mechanical issues with the boilers, the superintendent investigating the incident instead approved a night watchman to keep an eye on the boilers.

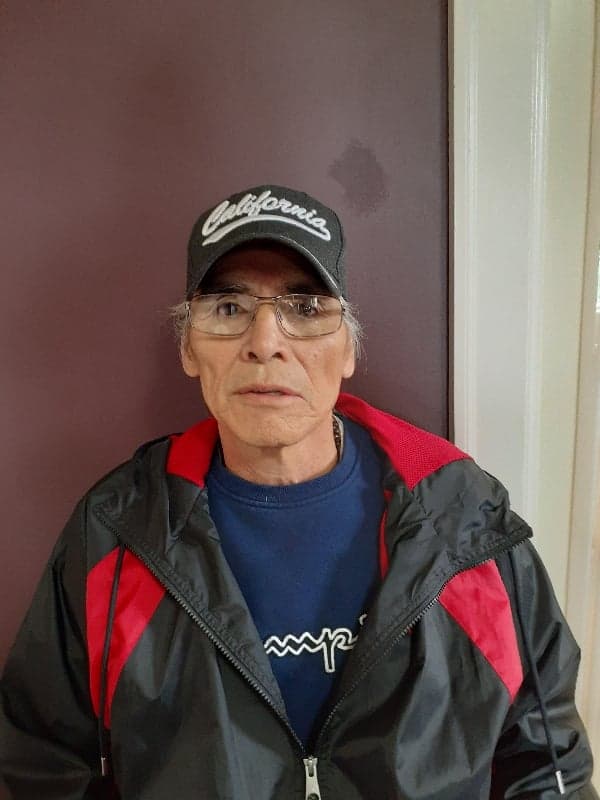

Ok my name is, my white name is Rex Back Fat but my Blackfoot name is Immitotokis. I am going to tell you about when I was living here at residential. This one incident…We are told the night before who will be going to the dentist, we have to be taken east to Crowfoot School. This friend of mine that I always go with, Ross LaFrance, he died a long time ago, but two of us mostly go the same time. When we get on a different bus to Crowfoot School, we don’t get off the bus. We hide in the bus the back of the bus, under the seats.

When we get to Shouldice [an area of the reserve], the bus driver never found out. Wayne Jones, one of the Jones was the bus driver at that time. We just wait for him to go inside, and it takes a while, and we slowly get off. That time lunches, our school lunches, there’s a box of school lunches, we take lots. Then we start walking to Shouldice, in winter, it was cold. Those times we were lucky it wasn’t that cold but still it was cold. We take a short cut to Shouldice to Many Bear Flats, the late Jasper Many Heads Sr. where he lives.

We go there and that’s where we stopped. Jasper would find out that we snuck away, and he would wait for afternoon when they get off the students, his kids, and he sent us back on the bus, back to Crowfoot School. First, we eat. When done eating, we are taken to the gym where the junior boys are. They put on boxing gloves on us to fight, it takes about a good two hours, I don’t know how many we fight, we take turns. Then maybe, when we get tired, they probably knew when we get tired, they phone Old Sun to come and get us, about 8 o’clock, we get back here.

The one named Mr. Brown, he takes us upstairs on the main floor, that kitchen is still there, right now, they feed us coffee, sandwiches, feed us and when we finish eating, they take us downstairs to the boy side that small room, our supervisor Miss Bolton has the clippers all ready, already hot, she cuts our hair and the clippers would burn our heads. Then they take us back upstairs and they strap us and go to bed.

This other incident the boys are hungry, during winter. Five of us go downstairs but on each floor is a lookout so three of us would grab food to eat, we throw anything into the gunny sack, we bring it back upstairs, we just put the gunny sack in the middle in the dorm and let boys eat. When done eating, then we eat.

Gyun

– Rex Back Fat

Oral interview with Rex Back Fat. Conducted, translated, and transcribed by Gwendora Bear Chief. Old Sun Community College, June 24, 2022.

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Old Sun C…

Read more

The Annex at Old Sun Community College. This Area…

Read more

The Fourth Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

The Third Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSCC…

Read more

The Second Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

Old Sun Indian Residential School operated between…

Read more