Old Sun Classroom

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

Read moreOld Sun Indian Residential School operated between 1929 and 1971. It has since been transformed into a culturally based post-secondary institution that offers certificates, diplomas, and degrees through partnerships with colleges and universities such as University of Calgary. The college is named in honor of Chief Naato’saapi, Old Sun.

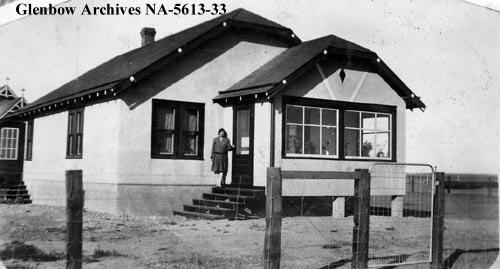

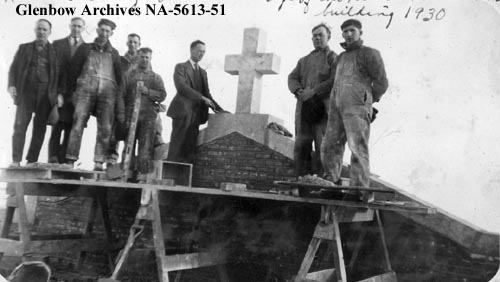

The signing of Treaty 7 occurred on September 22, 1877 and established reserves for all Indigenous peoples living in Southern Alberta, including the nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy [1,2]. Shortly after, Reverend John W. Tims of the Church of England was sent to found a mission among the Blackfoot, which was set up on the Siksika Nation reserve close to the location of Gleichen, Alberta [2,3]. Tims’ was involved in a variety of mission work for the Anglican Church, but his main focus was on the Siksika Mission [2]. Tims met with Chief Naato’saapi, Old Sun, who allowed him to build a cabin in 1886 which became the first Old Sun Boarding School [2,3]. Eight years later Tims established the White Eagle Boarding school for boys only. In 1901, these schools were amalgamated into a remodelled Old Sun Boarding school building where boys and girls attended together [2]. In 1911, the Government of Canada provided financial support for Tims’ work and a larger building was constructed the following year. This school was enlarged a decade later to allow for a larger number of students to attend. However, in 1928 the wooden frame building was burnt down due to a fire originating in the boiler room [2].

After this, the large brick building that is currently home to Old Sun College was constructed to serve as the Old Sun Indian Residential School for the following 30 years [2,3]. The school began with a capacity of 110 students, which was raised to 142 students in 1960. In 1969, the Government of Canada assumed control of the school and continued to operate kindergarten grade classes until 1971 when Old Sun Community College was established in conjunction with Mount Royal College as an adult learning facility [2,3]. Old Sun College was separated from Mount Royal College, now Mount Royal University, in 1978 when it became an independent institution run by the Blackfoot Nation. In 1988, the Old Sun College Act was passed in the Alberta Legislature transforming Old Sun Community College into a First Nations College [3].

Today Old Sun is a vibrant college led by the Siksika Nation that offers a wide range of accredited post secondary courses, including its own Siksika Knowledge courses. Academic programs at the college offer certificates, diplomas and degrees through partnerships with recognized colleges and universities.

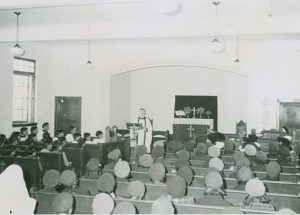

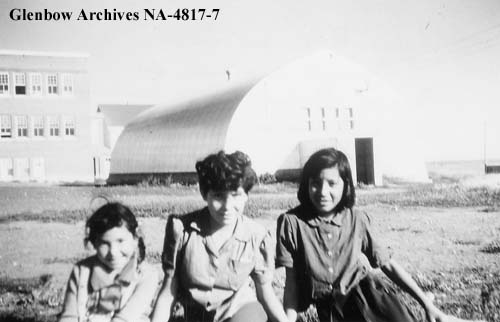

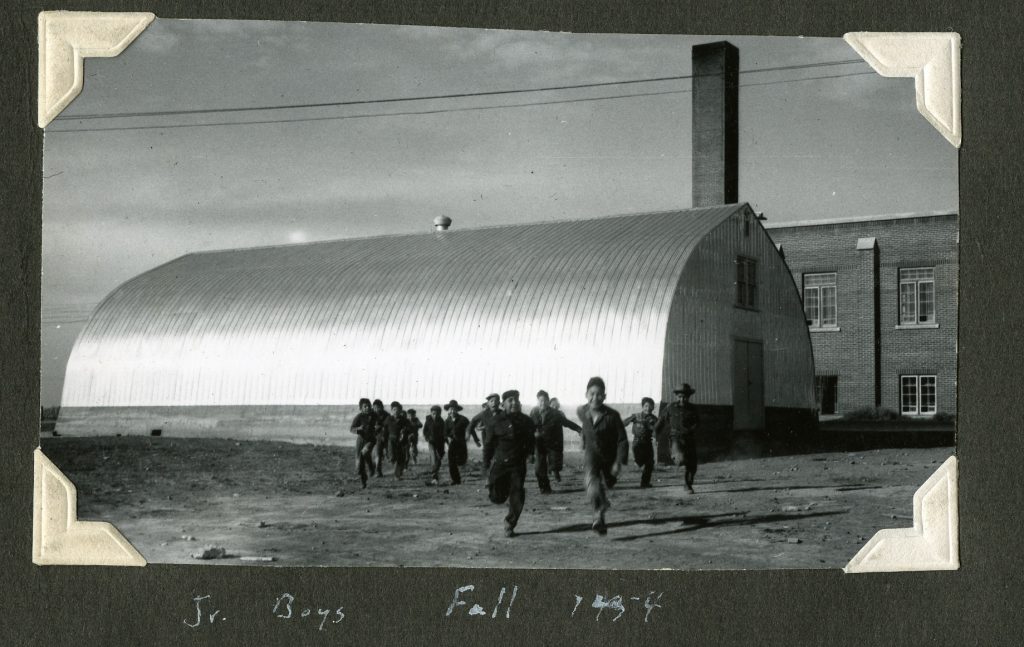

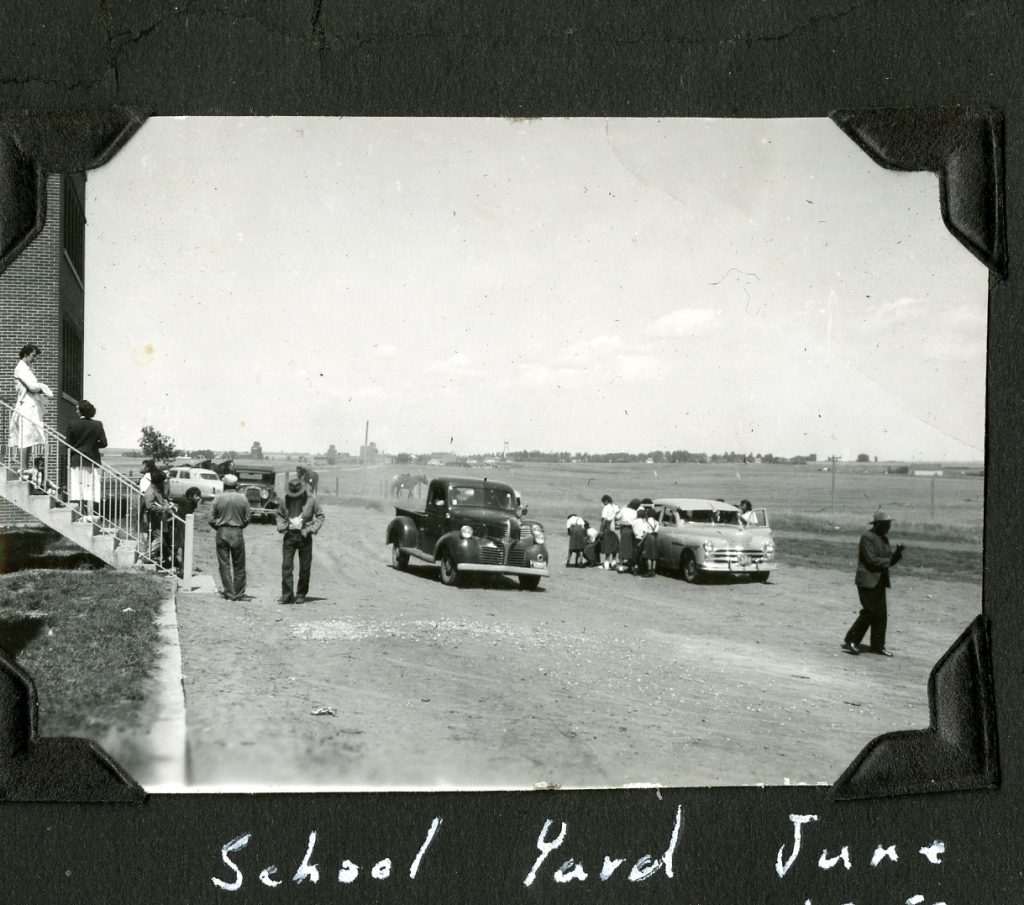

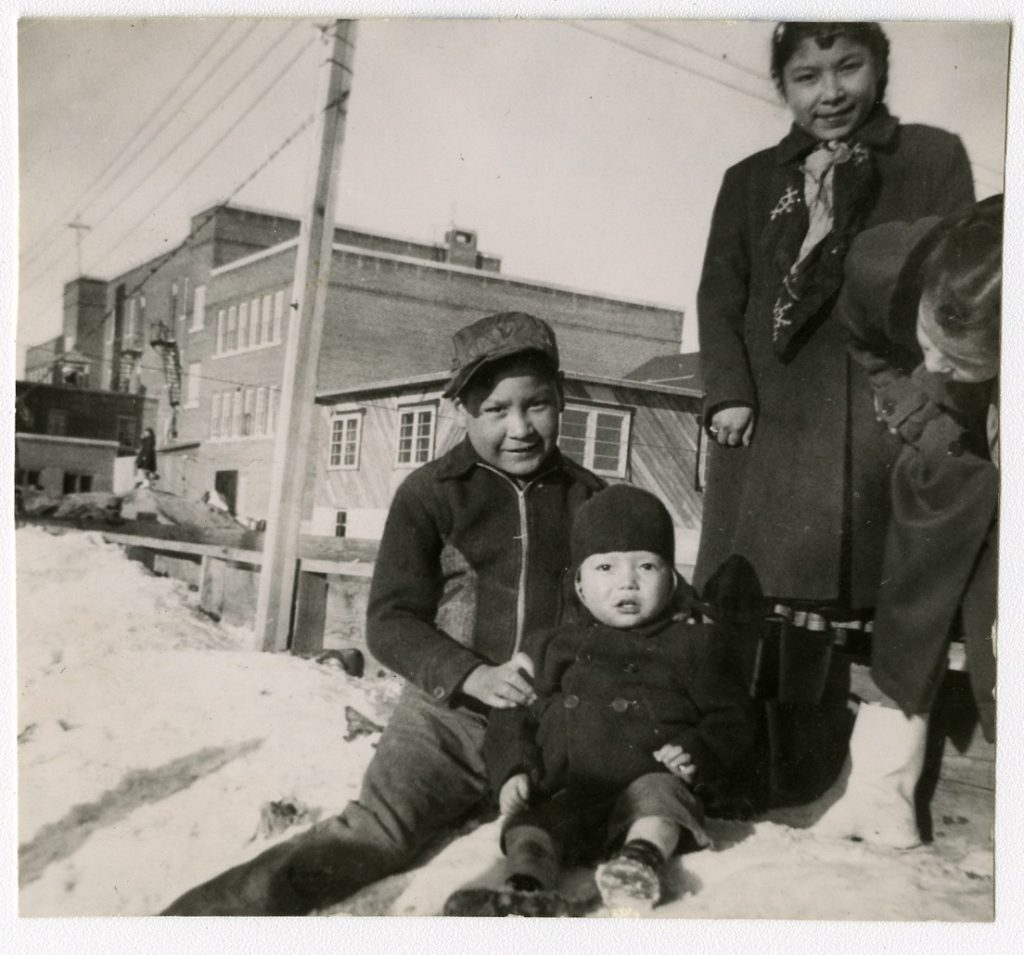

One of the most frequently recurring themes in the testimonies provided by residential school survivors to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a deep sense of loneliness and a desperate longing to be reunited with their families. Siblings attending these schools were often prevented from speaking with each other, even though they frequently attended events like mealtimes or church services together. While students could be transported great distances from their home communities to attend residential schools like Blue Quills and Edmonton Indian Residential School, those attending Old Sun were often able to see their houses and family members from dormitory windows and the school grounds. Being so close to their loved ones made separation from family members even more difficult for many schoolchildren.

Header image courtesy of Glenbow Archives.

[1] Tesar, Alex (2019). Treaty 7. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Electronic document, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-7, accessed June 29, 2021.

[2] Anglican Church of Canada (2020). Old Sun School, Gliechen, AB. General Synod Archives of the Anglican Church of Canada, Toronto, ON.

[3] Old Sun Community College (2021). About Us. Old Sun Community College. Electronic document, http://oldsuncollege.ca/index.php/about-us/, accessed June 29, 2021.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to look around. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel around the building's exterior by clicking on the floating arrows.

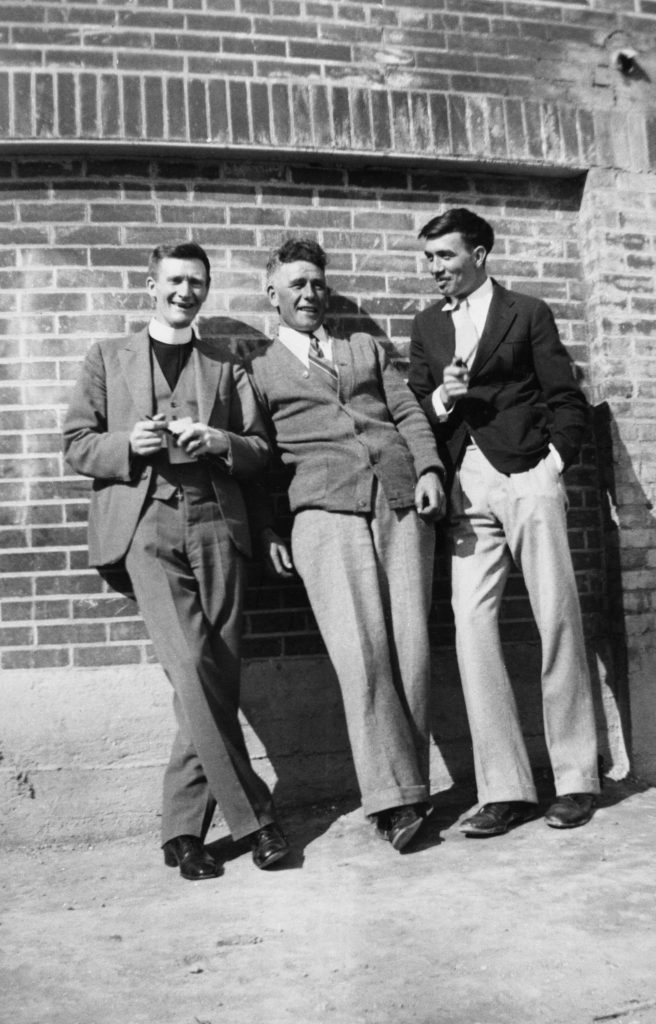

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos of Old Sun throughout its history. Click on photos to expand and read their captions.This image includes modern images of Old Sun. If you have historic photos of Old Sun and the grounds that they would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

![Blackfoot Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta - southwest view of main building. - [192-?]. P7538-672 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-672.jpeg)

![Blackfoot Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta - Southeast view of main building. - [192-?]. P7538-673 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-673.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alberta. - [193-?]. P7538-1021 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1021.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Blackfoot Reserve, Gleichen, Alberta. - [193-?]. P7538-1022 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1022.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Blackfoot Reserve, Gleichen, Alberta. - [193-?]. P7538-1023 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-1023.jpeg)

![The new Blackfoot school from the rear. - [193-?]. M55-01-P52 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/M55-01-P52.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alta. - Girls pulling carrots. - [193-?]. P75-103-S7-158 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-158.jpeg)

![Old Sun School, Gleichen, Alta. - Threshing. - [194-?]. P75-103-S7-175 from The General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-175.jpeg)

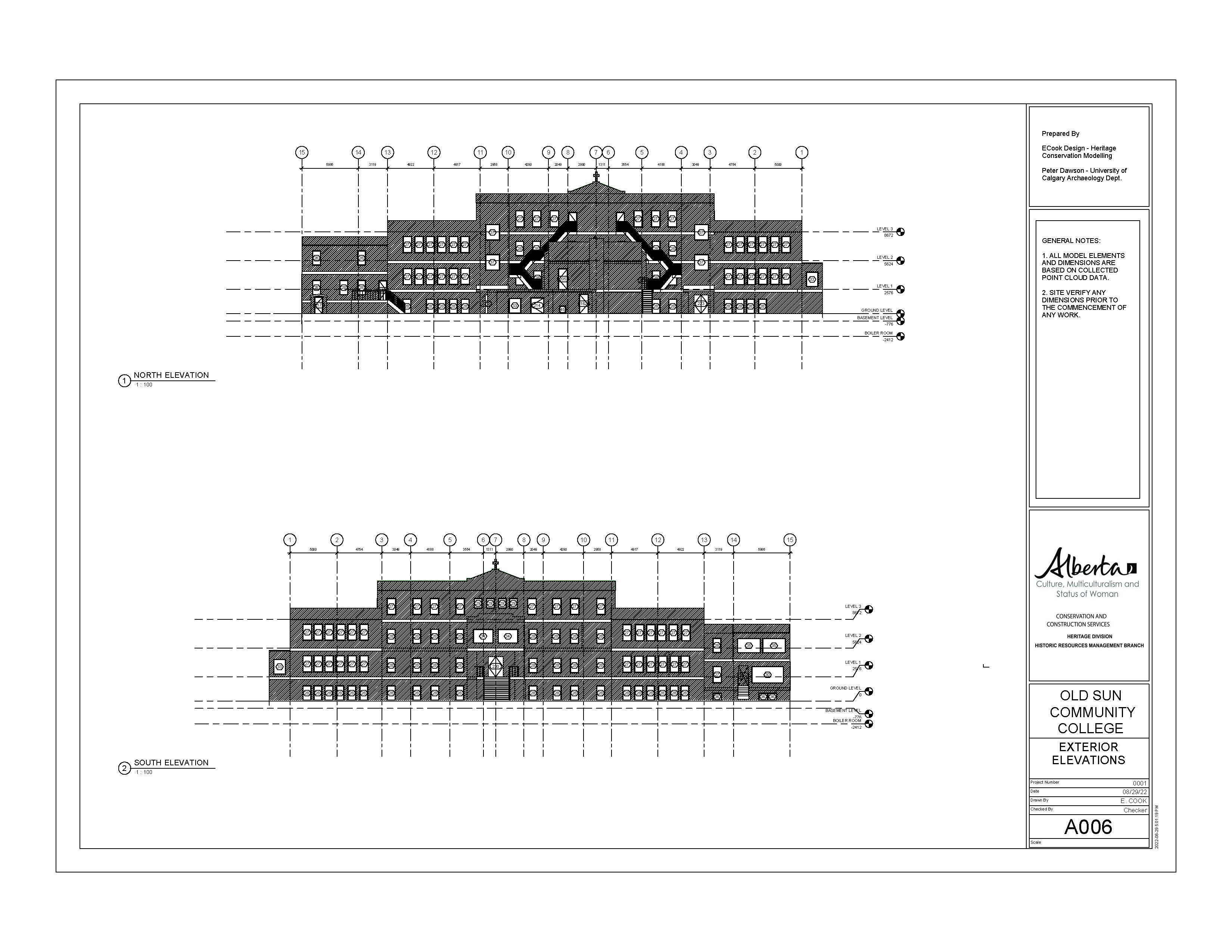

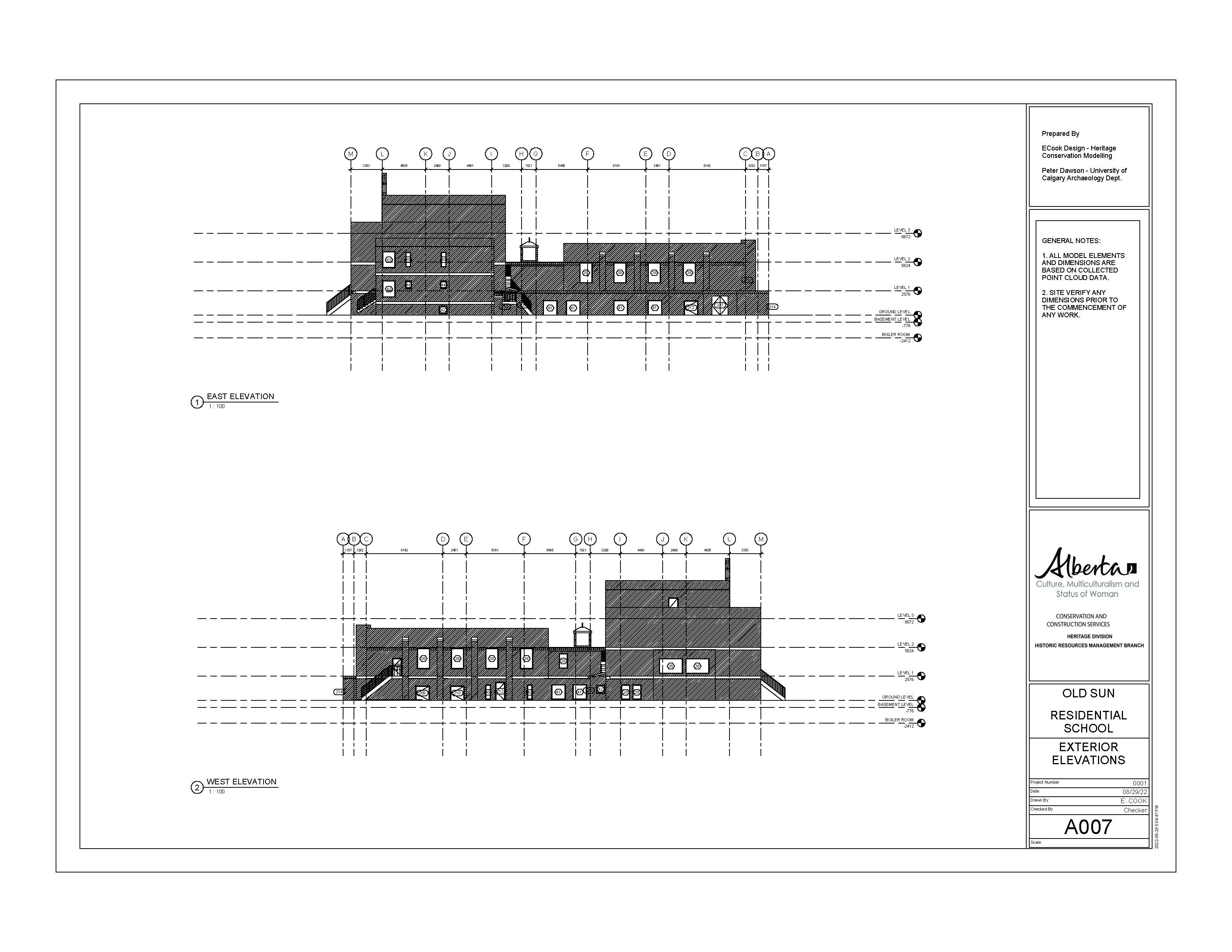

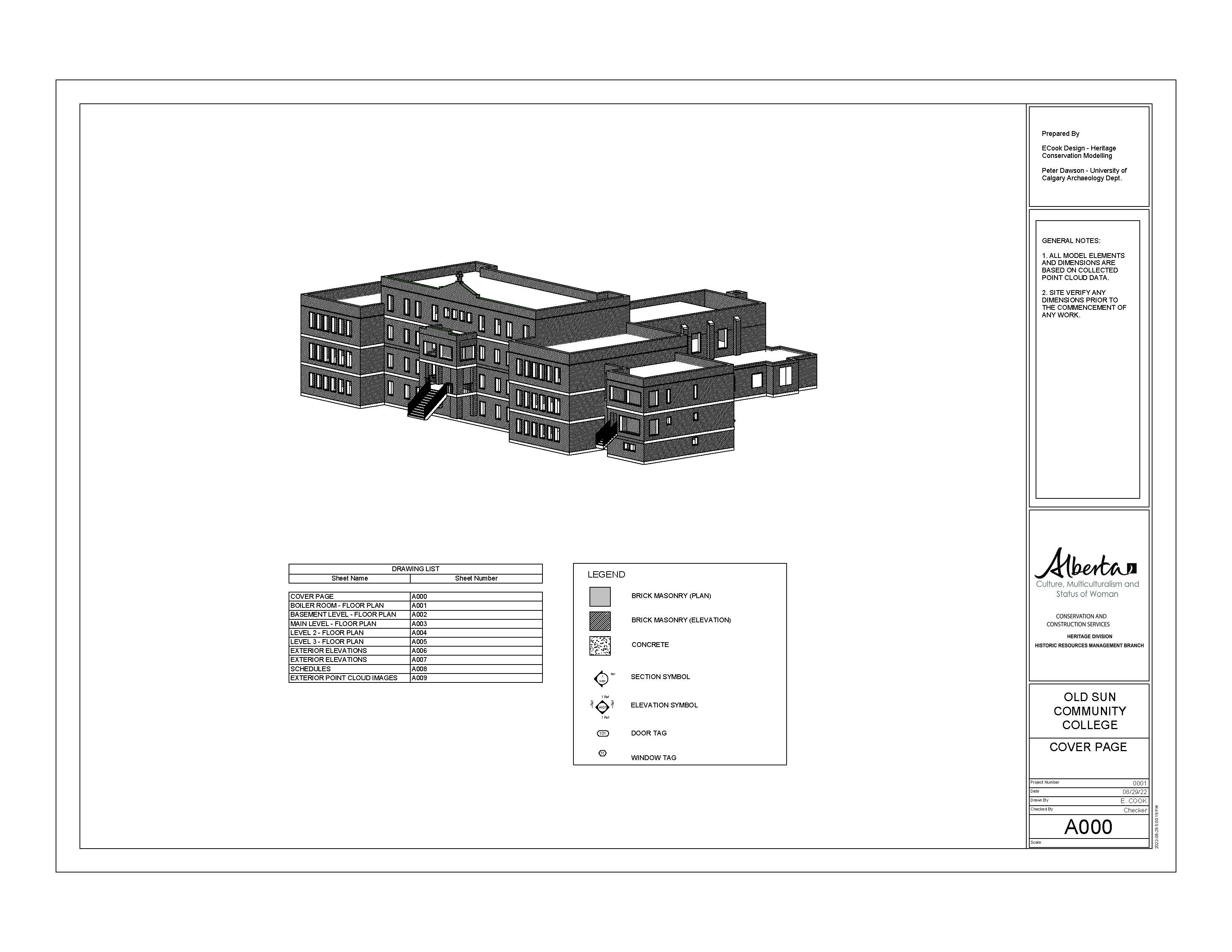

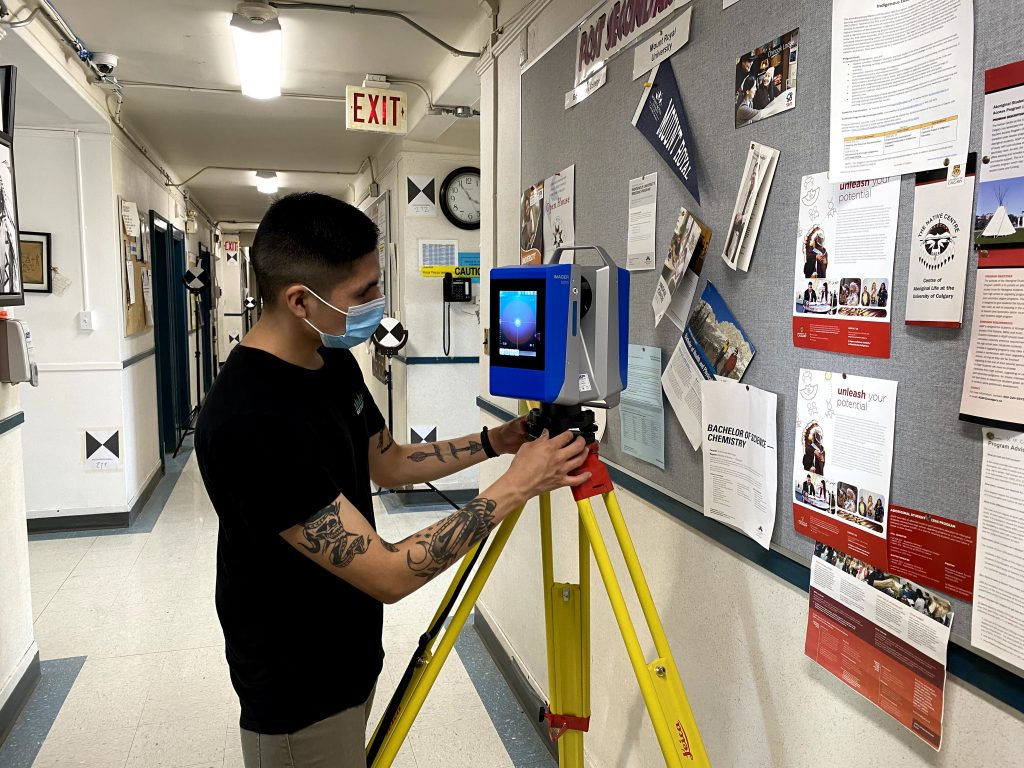

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger Building Information Model (BIM) of the school. A BIM is essentially a digital representation of the physical and functional properties of Old Sun. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee. They can be used to renovate, repair, and even replace the Old Sun Community College building should it ever be damaged or lost.

I think the most part the best part I liked about the residential school is when we got released to go out and play out in the yard. There was a bunch of garter snakes in the yard. I was the one that always chased everybody around. That’s why most of my punishments commenced. I’ve never been whipped by my parents till after I left residential school. I used to get whipped by a guy named Father Brown, he was kind of mad. He would just hit us with anything and smacks us in the head. Because, I guess, I don’t know if was my fault chasing everybody with garter snakes or what not… but everybody stayed away from me because of the snakes.

That’s when we were outside but inside was pretty… I think the worst bad experience, I think, of it all… It is Friday, they bring us home one the bus, but Sundays we had all had to start walking to the school no matter how cold it was on a Sunday morning or afternoon. I think that’s about all I could really think about residential school. I probably, what this lady said today at the workshop today, I only remember the little good parts and I think I blocked all the bad parts out. Cause I know there’s stuff out there like when we go out on the other side on the west side of the playground there was, like… we got to play with the girls and that was the only time we ever see them and what not, otherwise it was just like prison, as far as I’m concerned. I think the only good experience’s out of it is when I joined the army, I was already trained. I think that’s about my story. Like I said I was already trained cause we are always doing this we had to stand in line for breakfast and what not. We had to stick by rules.

So its always like I had a military life, all my life in residential. And then that is the sad part we grew up and my mom put us in residential school and then we kind of lost track of her. And then when they released us she got sick with cancer so she was in and out hospital, which made us miss part our mom’s life. I think that’s about it. I never really had a bad experience. Just when we were in the boy’s room and when the older boys were making the little boys fight each other. I guess that’s where the older generation became that’s how they all became boxers.

– Irwin Big Old Man

Oral interview with Irwin Big Old Man. Conducted, translated, and transcribed by Angeline Ayoungman. Old Sun Community College, May 12, 2022.

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Old Sun C…

Read more

The Annex at Old Sun Community College. This Area…

Read more

The Fourth Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

The Third Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSCC…

Read more

The Second Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Old Sun Community Coll…

Read more