Old Sun Classroom

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

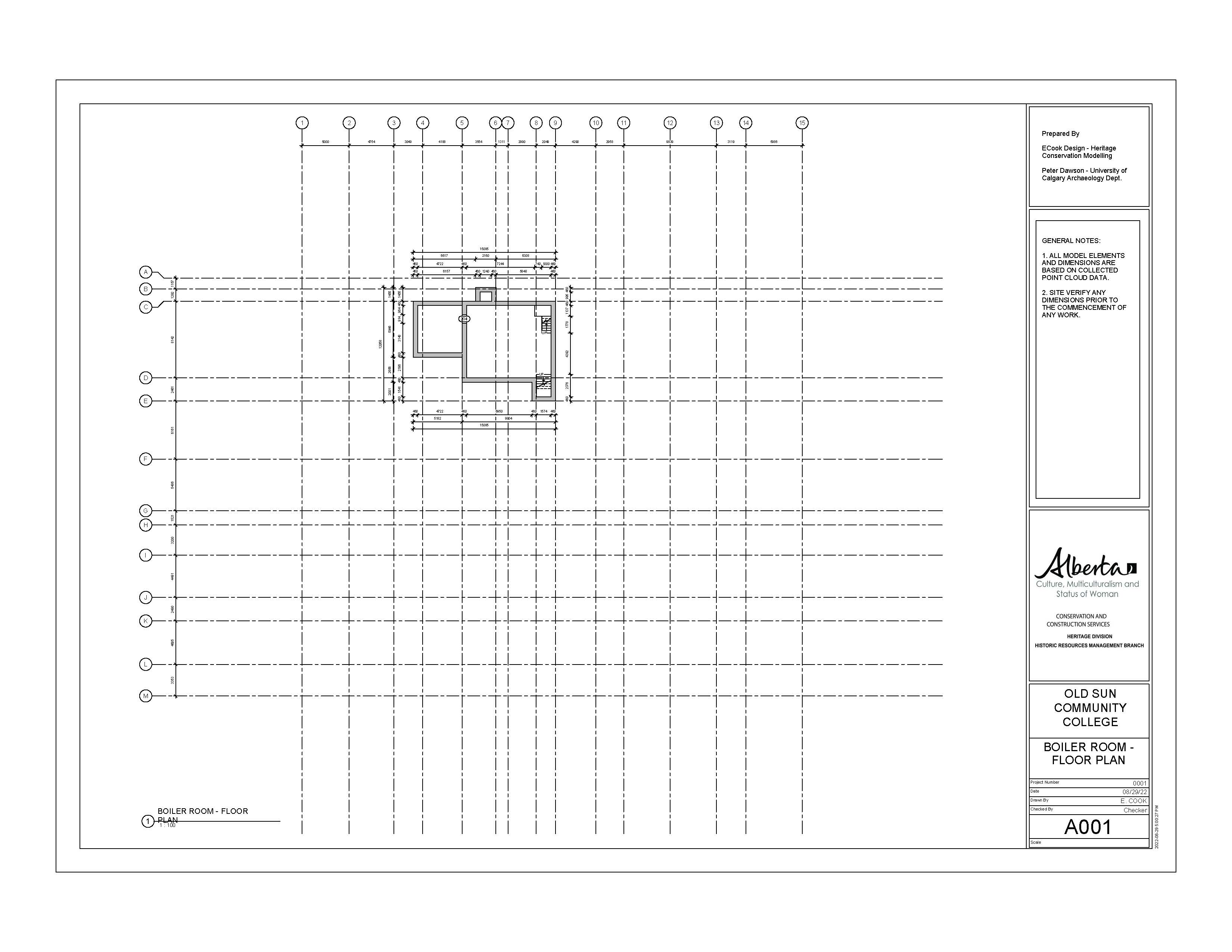

Read moreThe boiler room and former coal shoot at Old Sun Community College. This large space continues to house the utilities used to heat this large masonry building. A metal door leading to the coal shoot contains graffiti from students and staff that dates back to the early days of Old Sun Indian Residential School.

While there have been technological updates and modernization of the utilities, the boiler room retains much of its original appearance since its operation as part of Old Sun Indian Residential School.

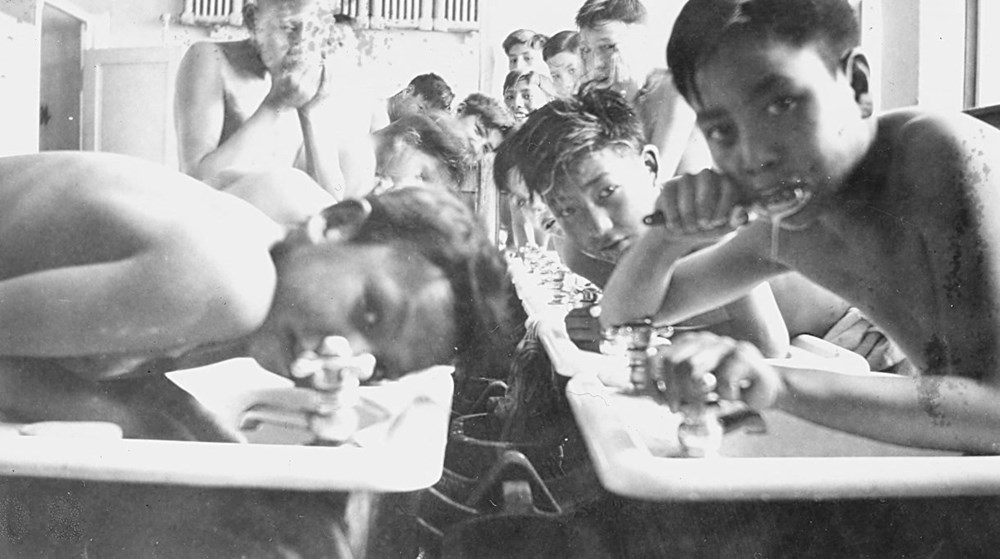

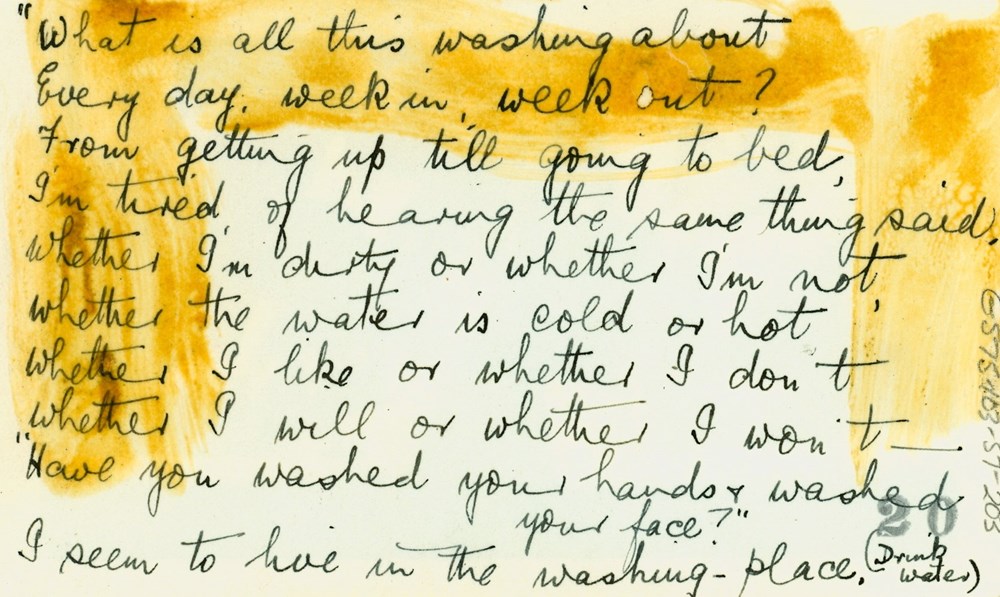

Students at the school were responsible for tasks related to the operation of the school such as laundry, washing dishes, harvesting food from the gardens, serving staff meals, taking care of livestock, and shoveling coal. Children working at these tasks would be assigned them both as daily living chores but also as punishments like having to clean the floor with a toothbrush, which as Mandel Old Woman recounts was a task given to students as young as the age of four years old. Other punishments included locking children up in isolated rooms or in remote areas of the school, likely including the boiler room.

While most of the boiler room at Old Sun is one area, the coal room is separated by a thick steel door, which is original to the 1932 construction of the school. Engraved on the door is a variety of graffiti from children who were in attendance of the school, including names, pictures, and dates that are legible as far back as the 1930s. This door provides a physical connection to the Old Sun residential school and the experiences survivors had while in attendance.

Archival documents reveal that fires were all too common at many Indian Residential Schools. The original Old Sun School at Siksika, for example, was constructed largely of wood and was lost to fire in June 1928. In this instance, Government investigators determined that the fire was caused by spontaneous combustion within the diary and storage cellar spaces within the building. In other schools, fires originated in basement boiler rooms where coal was burned to heat water as part of the hydronic heating systems. Other high-risk locations included kitchens and laundry areas.

Old Sun Indian Residential School (brick version) suffered its first fire within a year of its completion (1931). A fire caused by a defective heating element in one of the boilers had resulted from a small explosion. Investigators noted that the boilers in the basement of Old Sun were unmonitored at the time of the incident, suggesting that it could have been prevented. A second incident involving boilers occurred in 1947 and required an extended holiday break for students as repairs had to be undertaken to restore heat and hot water to the building. Rather than address the recurring mechanical issues with the boilers, the superintendent investigating the incident approved a night watchman to keep an eye on the boilers.

Many residential schools were located in remote rural areas and therefore were not easily served by municipal fire departments. As a result, the suppression of school fires required easy access to well-maintained fire extinguishers and dependable sources of water. Unfortunately, Government documents reveal that cost-cutting measures prevented many identified fire hazards from being addressed, placing students at significant risk.

To keep students safe, dormitories and classrooms required unobstructed fire routes to exterior stairways (fire escapes). However, there were no national standards in Canada requiring the installation of fire escapes for most of the residential school era. Instead, contractors took it upon themselves to make recommendations about when and where fire escapes should be installed. The general rule of thumb was that fire escapes should be fitted above the second floor of large multi-story buildings.

Well water quality and supply issues were well documented problems at all three of the schools preserved in this archive. At Old Sun, emergency repairs to well pumps and valves were required approximately one year after the school had opened. In October and November of 1932, reports indicate that the school was left without water for several hours. While well pumps proved to be a constant source of trouble, hydrological investigations revealed that a drop in the water table combined with an inlet pipe that had been laid incorrectly meant that major repairs were necessary. Even after repairs were undertaken, the supervising engineer reported that well tests indicated that only 2/3 of the water necessary for daily operation of the school were being produced. In some cases, it appears that water was withheld by some residential school administrators as a means of controlling and exercising power over the children.

Use the arrow keys (left, right, up down) or left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen.

This image includes modern images of the boiler room. If anyone has historic photos of the boiler room at Old Sun that they would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com or submit through "Submit your Memories" button at the top of the page.

![The previous, wooden, Old Sun school which burnt down from a fire started in the boiler room. [192-?]. P7538-673 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-673.jpeg)

![The previous, wooden, Old Sun school which burnt down from a fire started in the boiler room. [192-?]. P7538-672 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-672.jpeg)

![The previous, wooden, Old Sun school which burnt down from a fire started in the boiler room. [192-?]. P7538-638 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P7538-638.jpeg)

![Four girls make butter in the kitchens down the hall from the boiler room. [194-?]. P75-103-S7-165 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-165.jpeg)

![Back of the new Old Sun school, showing door into the boiler room next to the base of the chimney. [193-?]. M55-01-P52 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/M55-01-P52.jpeg)

![Students spent much of their time doing maintenance and chores for the school. Here, workshop boys build a brooder house. [194-?]. P75-103-S7-192 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-192.jpeg)

![Students spent much of their time doing maintenance and chores for the school. Here, workshop boys build a brooder house. [194-?]. P75-103-S7-187 from the General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada.](https://irs.preserve.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/P75-103-S7-187.jpeg)

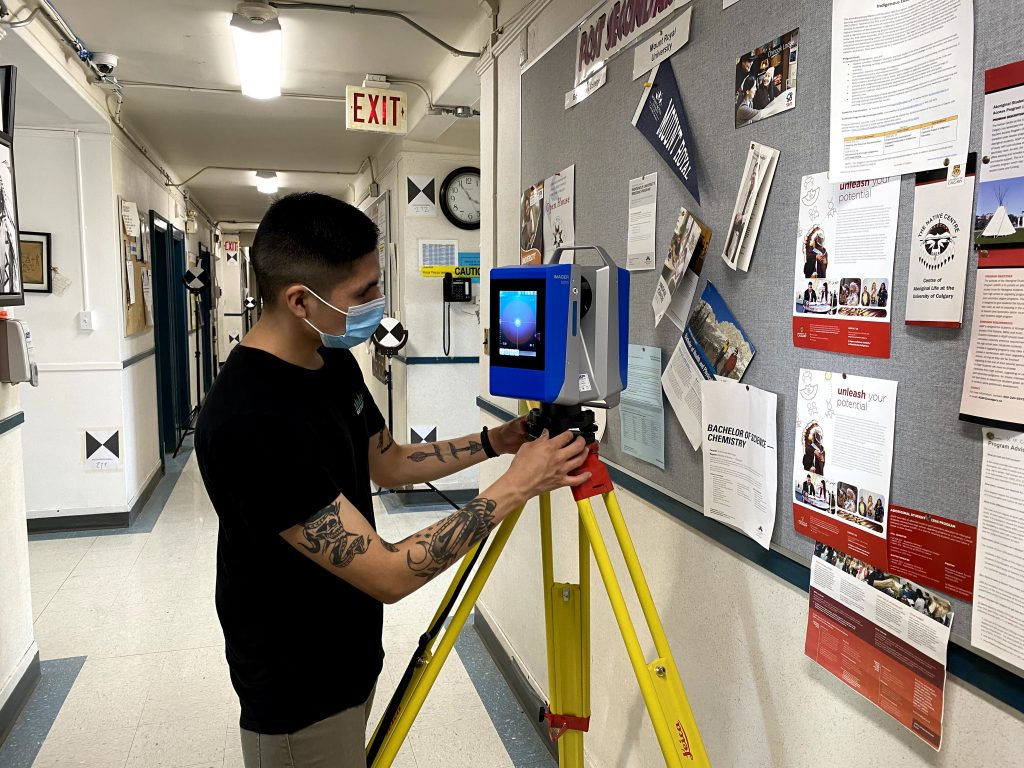

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee.

And another time, I ran away, this was during a blizzard that was the same time, it was a blizzard. I was the only one running away, hey. And I decided to run away. The same thing, very lonely, and the things that I go through, and all the things that like, like it was very… its worse than being in jail, this residential school. And its not, its I say its… You can’t, you can’t… you have to be follow their rules, and you know every little thing you do. Like you can’t even speak your own language. You get hit every so often. You get hit or you get strapped or get pulled by the ear or get knocked on the head. So, and…

Like we go to bed about, about, I say about 5, 5 o’clock in the evening and these things we were only about four or five years old so these things you know, it was very, you know I can’t… very, miserable out there. Some things that went through there… and at the age of four, I was, at the age of four I was doing cleaning. You know doing, doing the cleaning up at the age of four, you know. Like using, using a toothbrush to wipe the steps and gee there was a lot of, you know. At my age of 4 years old, what are you doing using the grooves to, you know, scrub the floors and you know and that was, for a four year old… for a four year old doing that, and mopping and scrubbing the floors and polishing the floors with a machine. You know at four years you’re not supposed be doing that.

And you eat the same old food, out there, you know, you get tired of. And you wear the same clothes, the same clothes over and over. And yeah, it was very miserable out there. And you can’t speak your own language, you lost your language and that’s how I don’t know my language to this day. Umm not my language, my culture I should say yeah. I lost my culture. I don’t even know my culture to this day. I’m at the age of 63 years old now. I just know, just know a few things about my culture now, and now I have to relearn to speak English.

And it was very hard and when we were in the chapel we, umm, when we were, when we go chapel it goes on for hours and hours. I don’t know how long, how long it goes on and we’re sitting there praying we have to get on, on our and our knees for about I say about… I don’t know, an hour two hours and our knees would be… I don’t know, be gee be very, umm, its very sore our knees. And we do fall asleep, and we get slapped on the head. And you know, so we have to keep, keep awake and you know and by the time we’re tired so… I don’t know we get, we get umm.. we get how do we say… We get like, umm like, we get we get punished for that you know. You know so that was one of the things too.

-Mandel Old Woman

Oral interview with Mandel Old Woman. Conducted, translated, and transcribed by Gwendora Bear Chief. Old Sun Community College, May 5, 2022.

This computer reconstruction approximates how clas…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

This computer reconstruction approximates how the…

Read more

The Annex at Old Sun Community College. This Area…

Read more

The Fourth Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

The Third Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSCC…

Read more

The Second Floor of Old Sun Community College (OSC…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Old Sun Community Coll…

Read more

Old Sun Indian Residential School operated between…

Read more