UnBQ Boiler Room

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

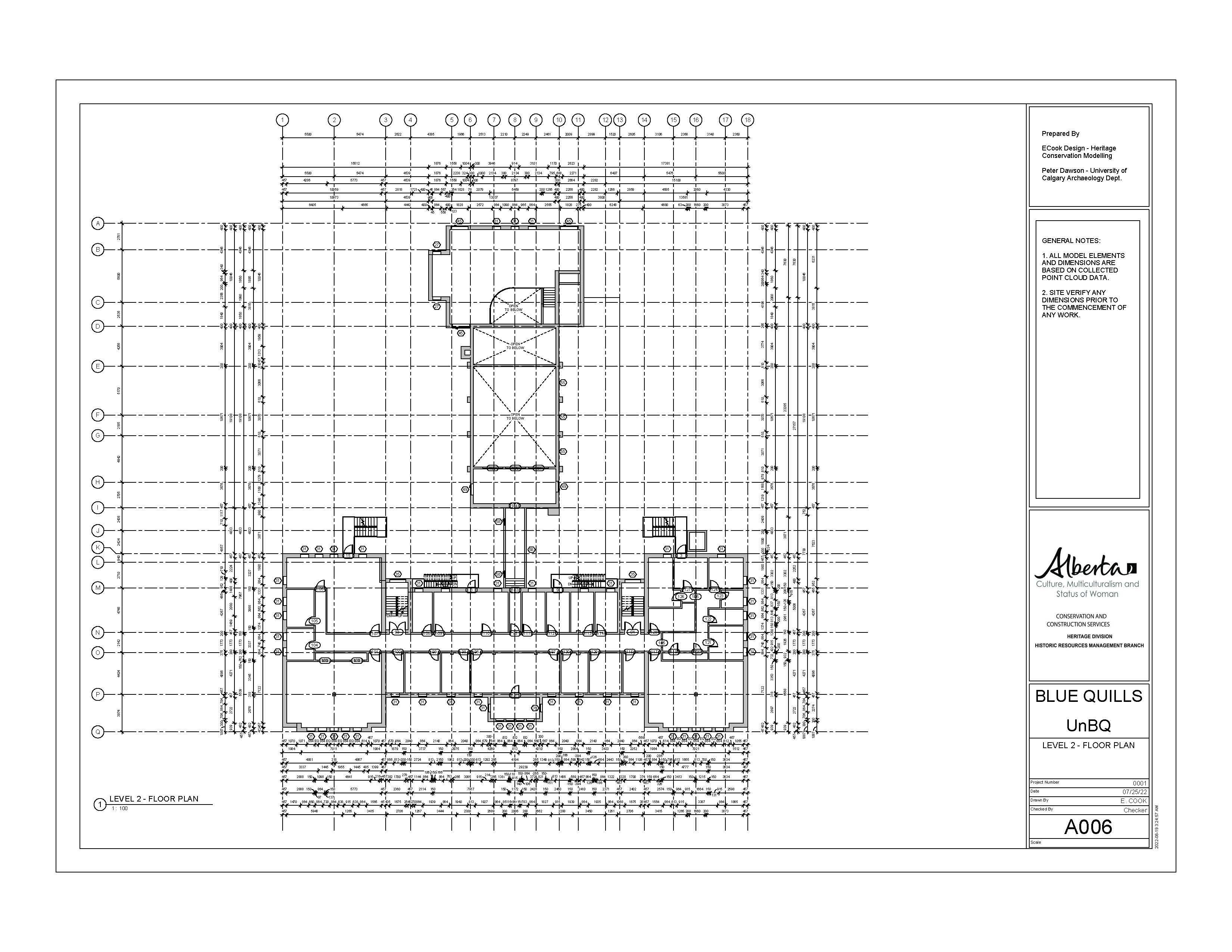

Read moreThe 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). Important rooms on this floor include the junior boys and girls dormitories and the boys and girls Infirmary. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions.

Today the second floor/third story of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ) houses a combination of offices, classrooms, and a staff kitchen. At the center of this floor, access to a mezzanine above the library can be gained. This space is used as a meditation room, but originally functioned as the choir house for the chapel.

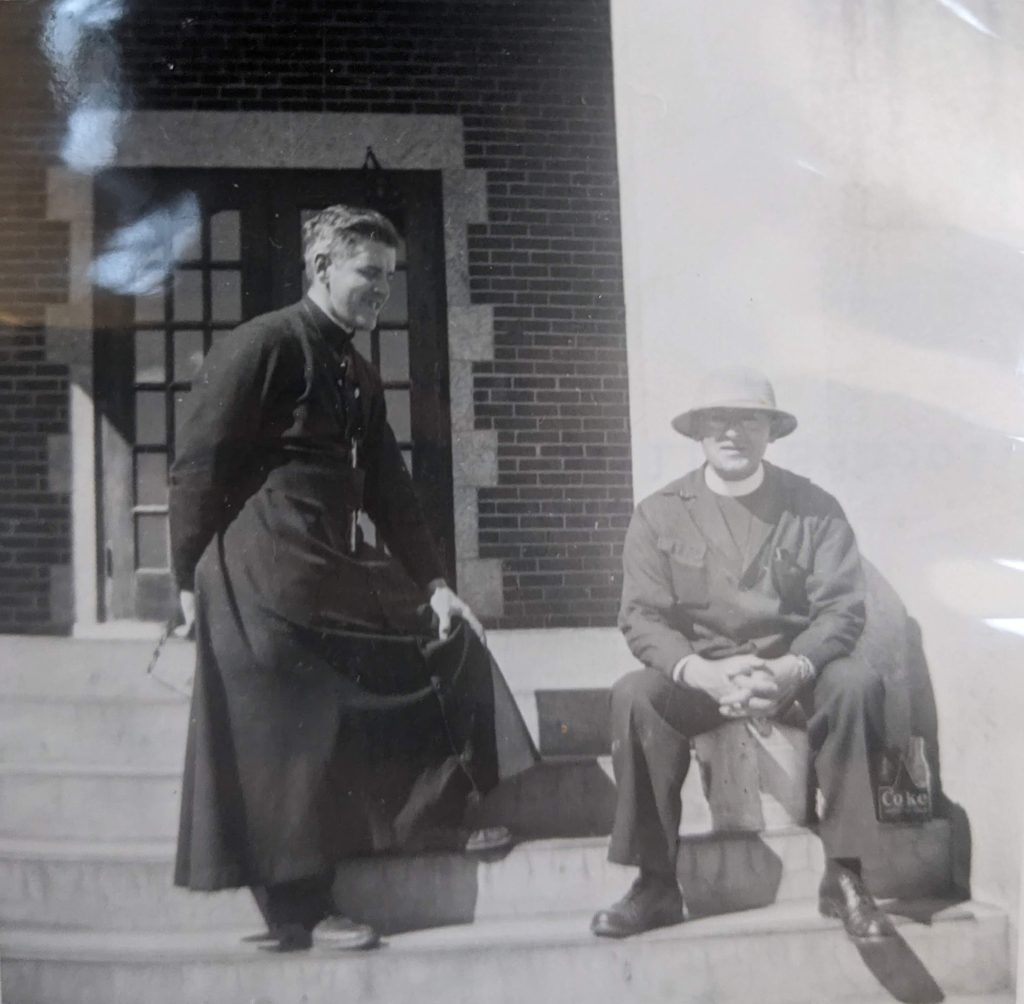

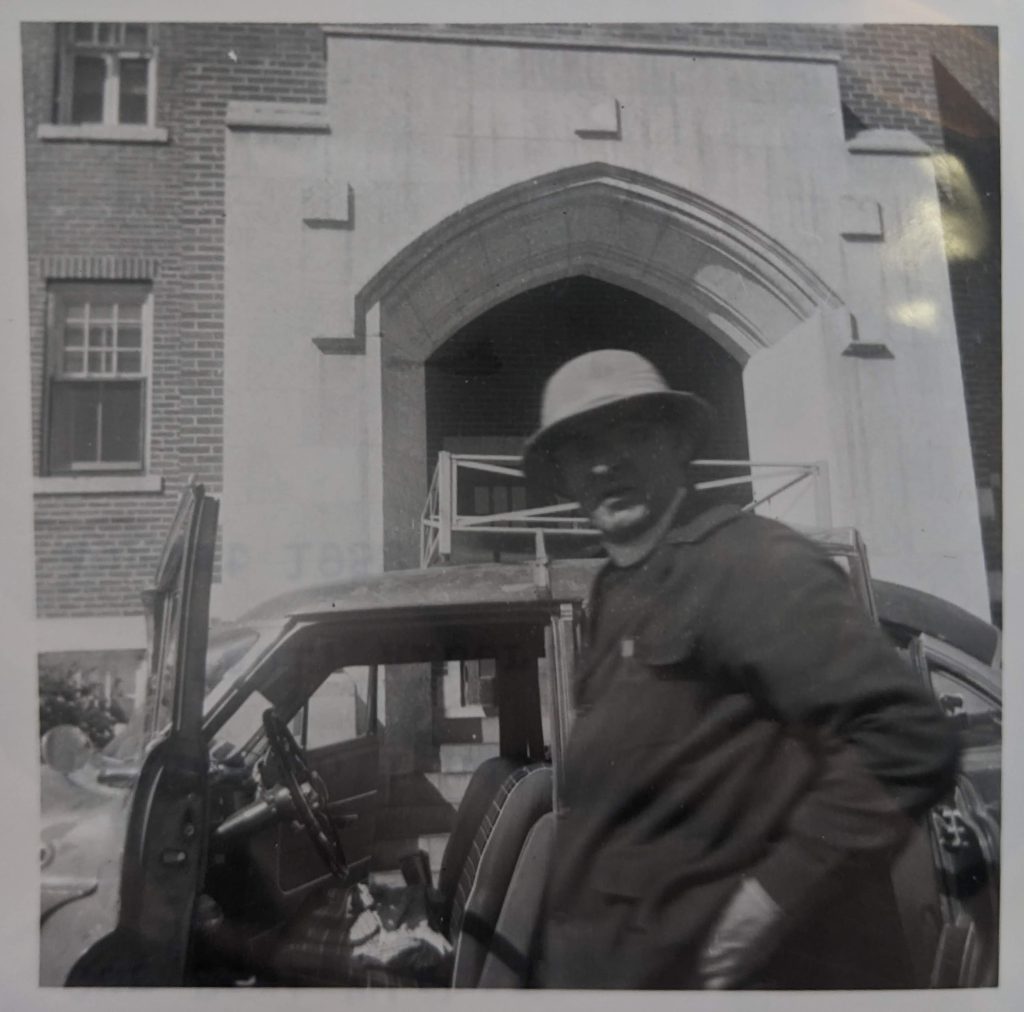

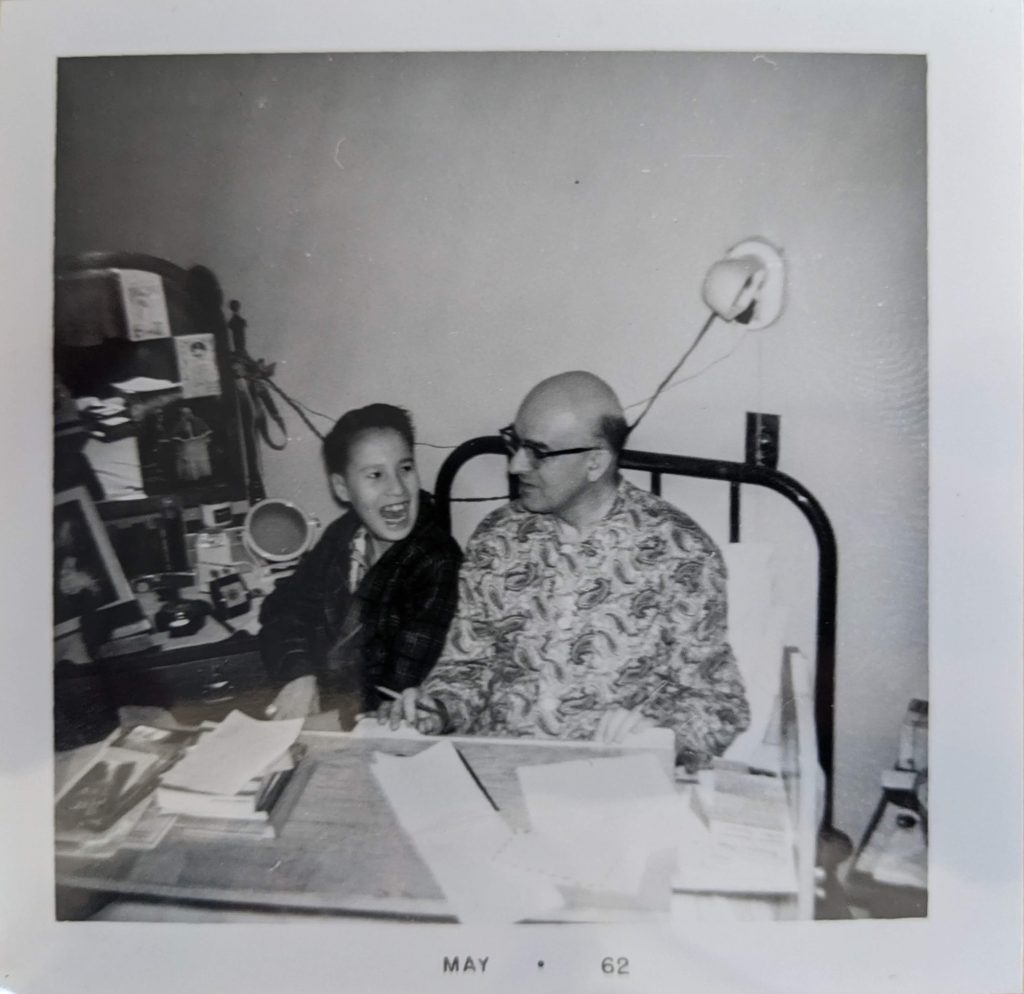

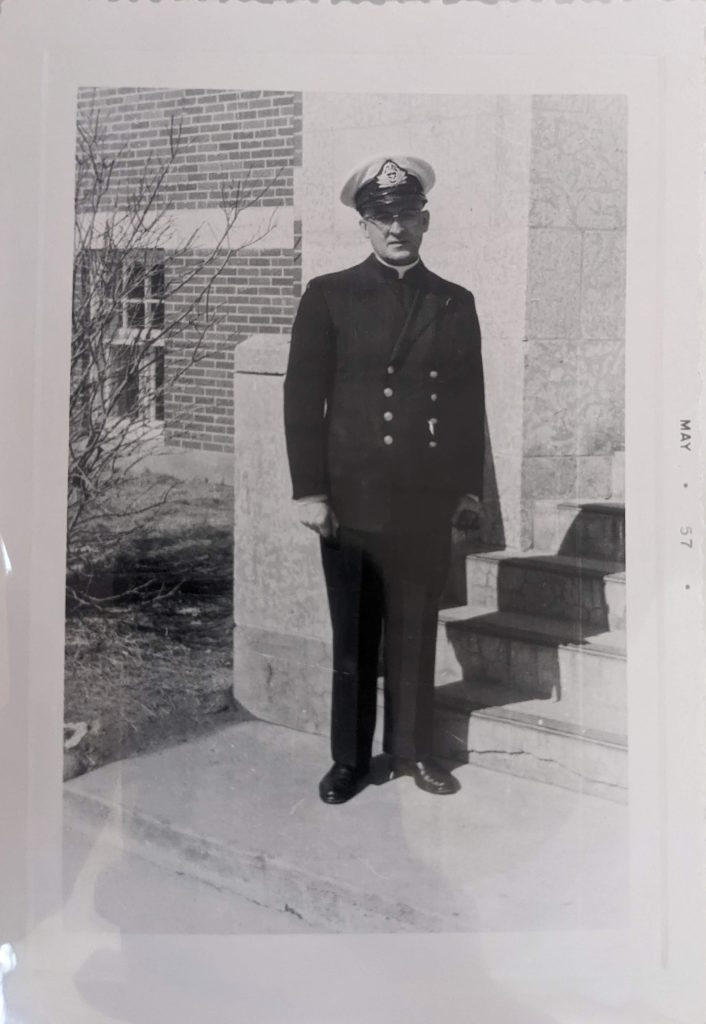

When in operation as a residential school, this floor housed some teaching spaces, such as classrooms and a sewing room. The mid section of the floor was used primarily as staff quarters for supervisors, teachers, and maintenance workers who lived on-site at the school. The principle, who was often also the priest would also live on the premises, although in his own separate house alongside his family. The groundskeeper likewise had a house separate from the main school building.

Relationships between staff and students were often difficult. The students’ dormitories were on the floor above the staff, with supervisors intentionally situated between students and building exits. Students were strapped with thick leather belts from farm machinery for not following rules such as being quiet or as Verna Daly remembers, for speaking Cree or Dene, the home languages of many of the students at Blue Quills. Marcel Muskego recalls being strapped in the hallway so other students could hear his screams, and does not recall what the punishment was given for.

Generally, staff created a better living experience for themselves in the school than they did for the children they were responsible for. For example, supervisors ate in a separate room off the dining hall with ornate table settings and “great food while we ate garbage,” remembers former student Jerry Wood.

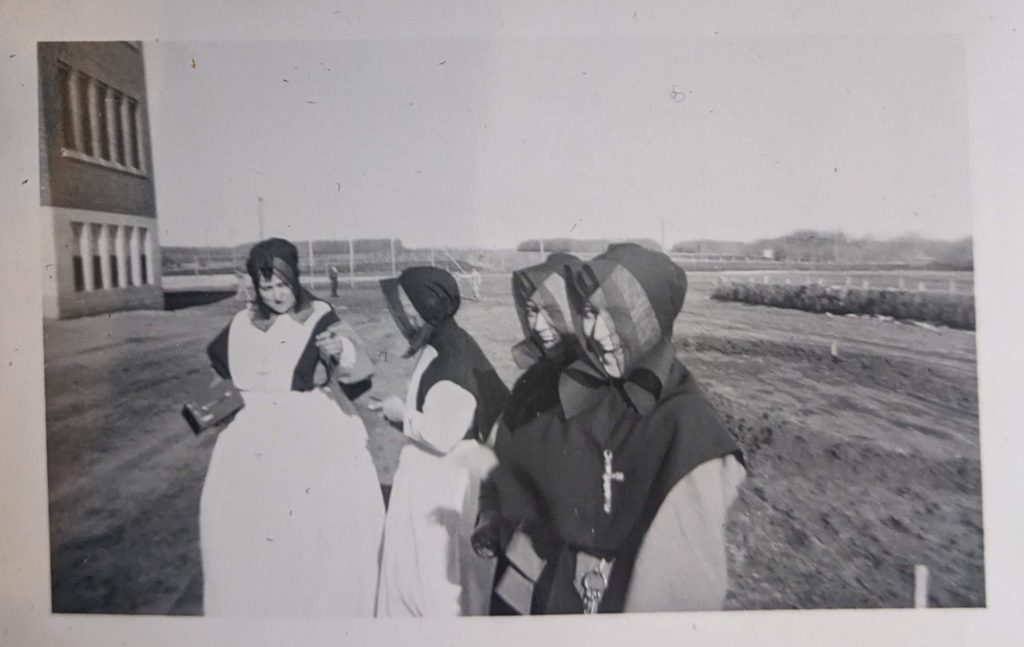

Not surprisingly, overcrowding led to an increase in the spread of communicable diseases in all three schools. Most concerning was the spread of TB. At OS tuberculosis was on the rise in 1935 with five students in the hospital and the remaining student population put under observation with a rest period every afternoon (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6360, Reel C-8714, 1935). Two years later, the Indian Agent reported that nurses with TB experience attended the school because of the high need, but that this service must be funded by the band. The Agent questioned if this on-going medical funding to treat TB should be a departmental obligation (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6360, Reel C-8714, 1937). Correspondence from the Saddle Lake Agency in 1941, noted that a polio outbreak had occurred at both BQ and EIRS, and that the students returned to school on September 23 after the ban was lifted. There was no other mention or details provided about the duration or severity of the outbreak (Saddle Lake Agency, Volume 6346, Reel C-8703, 1941).

The DIA sought solutions to reduce disease transmission by looking at the bathing practices rather than addressing the problems with overcrowding. At BQ showers replaced washbasins in an attempt to limit the spread of communicable health conditions like scabies and impetigo. Ironically, the washbasins were repurposed at another school as a cost cutting measure – despite the believe that they were the source of disease transmission.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel to different areas of the third floor by clicking on the floating arrows.

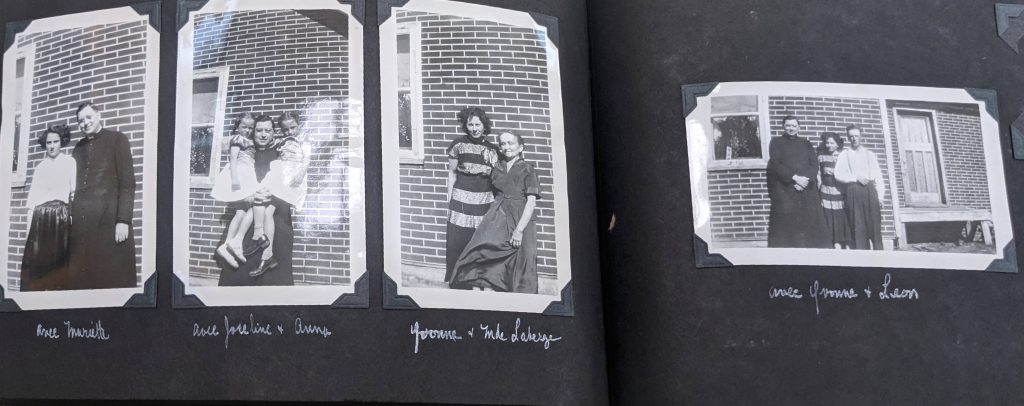

This image gallery includes modern and archival photos of UnBQ's third floor.

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee.

Some of the threats faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans contained in this archive, which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. There were three specific areas that placed the health and safety of students at great risk: Fire Hazards and Protection Measures; Water Quality, and Sanitation and Hygiene. As you explore the archive, you will find more information about the nature of these hazards and their impact on students.

Hello. I want to thank my little brother, Felix, for sharing. This is the first time we’ve been together here in a circle, and there’s been a few triggers, bringing tears to my eyes. Thank you Felix.

My name is Marcel Muskego, I am a 65 year old. I attended Blue Quills school. My institution started at Charles Camsell Hospital at 1952-1954, and that’s when I was brought to Blue Quills, where I remained until 1965. It wasn’t easy being there, went through to a lot of rough times in there.

At a young age, I was one of those people that, I was a bed wetter, from, well, when I got in there. Every day they make me wash my clothes, that went on most my years in school. The thing about it is they make me wash my own, my own bedding. Ring it out by hand, stand on a chair… They used to make me go on a girl side and go hang my bedding out. The sisters, girls, over there would be laughing at me, some of them.

And like Felix said, I learned to be hard person, not caring person. fight all the time. Blue Quills was predominately Cree, about 80%. I’m Dene, we only made up about 20% at that school.

Yeah, I remember the strappings I used to get for being bad. My first recollection is grade three. I don’t know why I got a strap, but I got a strap. Not in public but they had the classroom doors open, they had a stool they’re out in the hallway and they put me there and they gave it to me. They had the doors open so other students can hear me cry out.

Things like that happened all… just anytime I was bad I got a strap, and I remember one strap I got by the principle. And that was when I was in grade seven. Just we were fooling around, poking a student with a pencil, and that pencil broke on her arm. Sent me to the principal’s office and I got a strap with a combine belt, with the clasp still on there. I have scars on my wrist from that strap. Yesterday I saw a picture of a person that did not to me, first time ever seen those pictures.

– Marcel Muskego

Marcel Muskego Testimony. SC149_part06. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Circle. March 28, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SC149_part06

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read more

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more