UnBQ Boiler Room

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read moreThe basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). Significant rooms include the boys’ and girls’ playrooms, dining room, kitchen and laundry facilities, and the boiler room. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions.

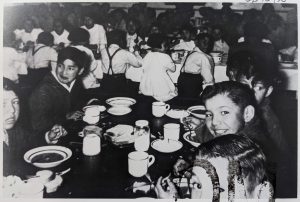

The west side of UnBQ’s first floor includes an art room and a classroom. The central area contains a large cafeteria that connects to a small sitting area with access to lockers, bathrooms, and another classroom. The entrance to the gymnasium, which was opened in 1969 , is accessed from the east side of the sitting room. A corridor leading north from the cafeteria provides access to a kitchen and pantry. Further down the corridor is the boiler room which now connects to the library on the second floor via a later addition to the building. Along the hallway between the boiler room and the cafeteria is the laundry room, as well as various utility rooms, maintenance offices, and storage rooms.

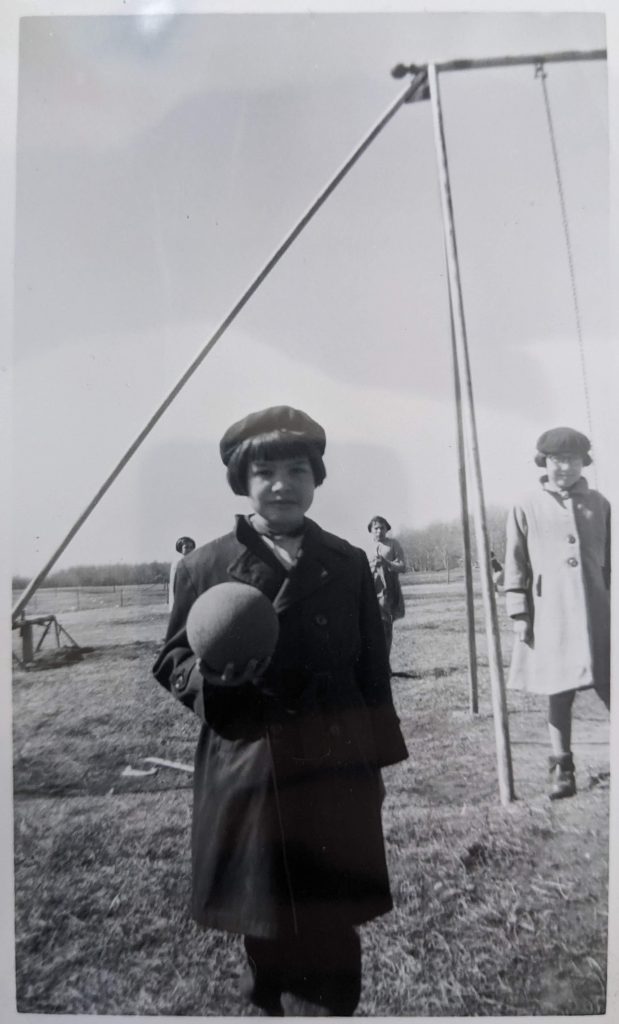

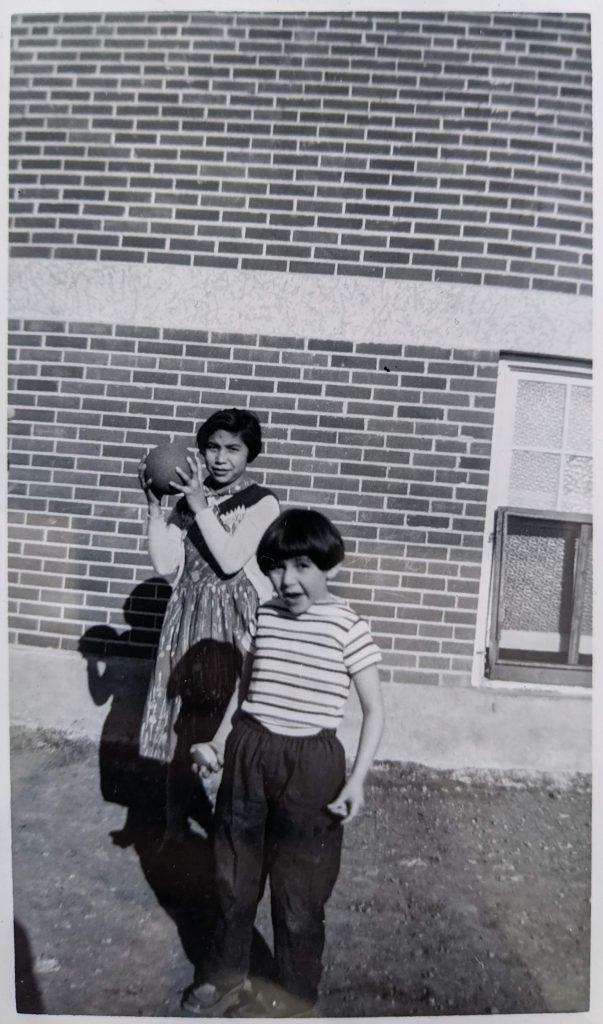

When UnBQ operated as a residential school, the students were spatially separated along gender lines. Each floor of the school was largely symmetrical, with the west wing containing the girls playroom and the east wing the boys playroom. On the west side, the classroom and art room were originally joined into a single open space which made up the girls’ playroom. The bathrooms appear mostly as they would have in the past. For example, the tiling, walls, and even the hooks and numbers for girls’ toothbrushes still remain today. However, a large circular sink and communal shower no longer exist. The adjacent bathroom would have contained a bathtub which has also been removed.

Likewise, the sitting area and classroom at the east end of the first floor would have once been joined to form the boys’ playroom. The bathrooms would also have contained a communal sink with adjacent shower space similar to the arrangement on the girls’ side.

The bathrooms often feature prominently in survivors stories because many students were quite modest and not used to communal bathing arrangements. The size and scale of Blue Quill’s many floors also made the building quite imposing to many students. Margaret Cardinal recalls, “when we got to Blue Quills, we were herded into this cave, I’d never seen such a huge cave, I didn’t know at the time that it was a gym. It had big windows on the top but none that you could look out, it was very scary.”

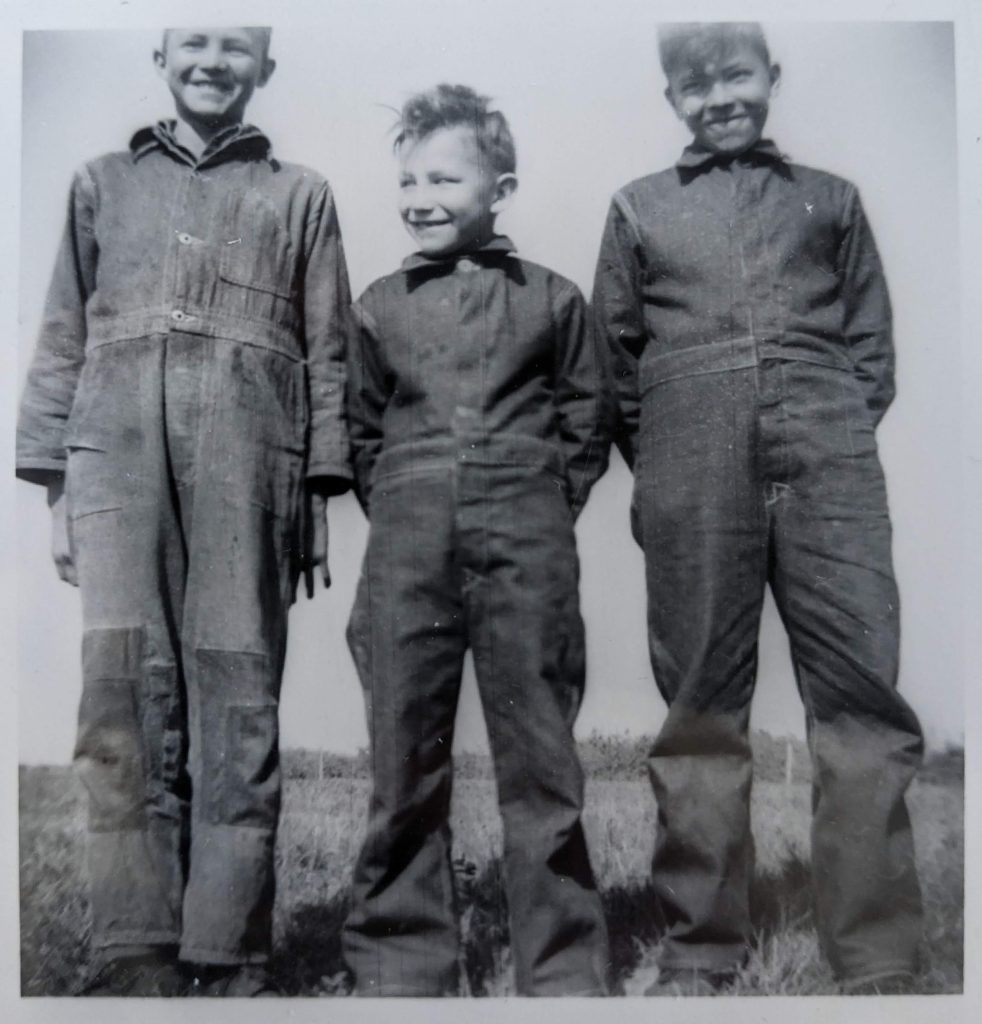

When students were brought to the school, they would have their hair cut and undergo a harsh cleaning to scrub them of perceived dirtiness or parasites. Much of this would have occurred in the bathroom areas of Blue Quills. Jerry Wood remembers having his hair cut and being covered in kerosene to kill possible lice.

The risks faced by children were not just due to the multitude of safety hazards relating to fire, sanitation, and nutrition, significant risks also came from the adult staff that shared the very same building. Corporal punishment was commonly meted out for various infractions and could include both physical abuse and public humiliation. Children experiencing bed wetting were often forced to carry their soiled bedclothes through public spaces like dining halls. Others were routinely strapped as a form of punishment.

Food insecurity was prevalent within these schools as well. Children were intentionally fed less and poorer quality food than the staff were served. They were also responsible for growing much of their own food in the schools’ gardens, and tending to the livestock. Blue Quills had their own cows, which according to a study by the Acimowin Opaspiw Society (AOS) were not subject to routine safety inspections by the Department of Indian Affairs, the federal branch responsible for insuring the safety and quality of schools’ food-stocks. The AOS has deterimined that hundreds of children died at Blue Quills from drinking unpasteurized raw cow’s milk and contracting tuberculosis or other fatal milk-borne illnesses [1].

Leah Redcrow, executive director of the AOS said to Global News, “The school administrators knew this… That’s why the children were getting sick and dying and not the school administrators..” “The school had a cream separator. All the cream would get loaded into a rail cart and be shipped off for pasteurization. All the raw skim milk filled with disease was fed to the children” [1].

The mission statement for Indian Residential Schools was to transform Indigenous students into facsimiles of Euro-Canadian school children. A survivor from Blue Quills IRS, Verna Daly, recalled that when she arrived at the school she met with her older sister in the bathroom. Her sister instructed her “don’t cry, don’t talk our language…you’ll get strapped. Or you’ll get your mouth washed out with soap” (Daly, 2013). An anonymous Survivor from BQ spoke about the staff forcing the students to perform cultural dances and then mocking the students:

“But they had laughed at some of this, you know, make us do some

of the things that was culturally done, eh, but to turn it around and

make it look like it was more of a joke than anything else. It was

pretty quiet when we would do those little dances. There was no

pride. It’s just like we were all ashamed, and we were to dance

like little puppets” (2014)

[1] Mertz, E. “Children died from drinking unpasteurized raw milk at Saddle Lake residential school: advocacy group.” Global news, electronic document https://globalnews.ca/news/9432774/saddle-lake-cree-nation-residential-school-investigation-report/, accessed October 26, 2023.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel to different areas of the first floor by clicking on the floating arrows.

This image gallery includes modern and archival photos of UnBQ's basement

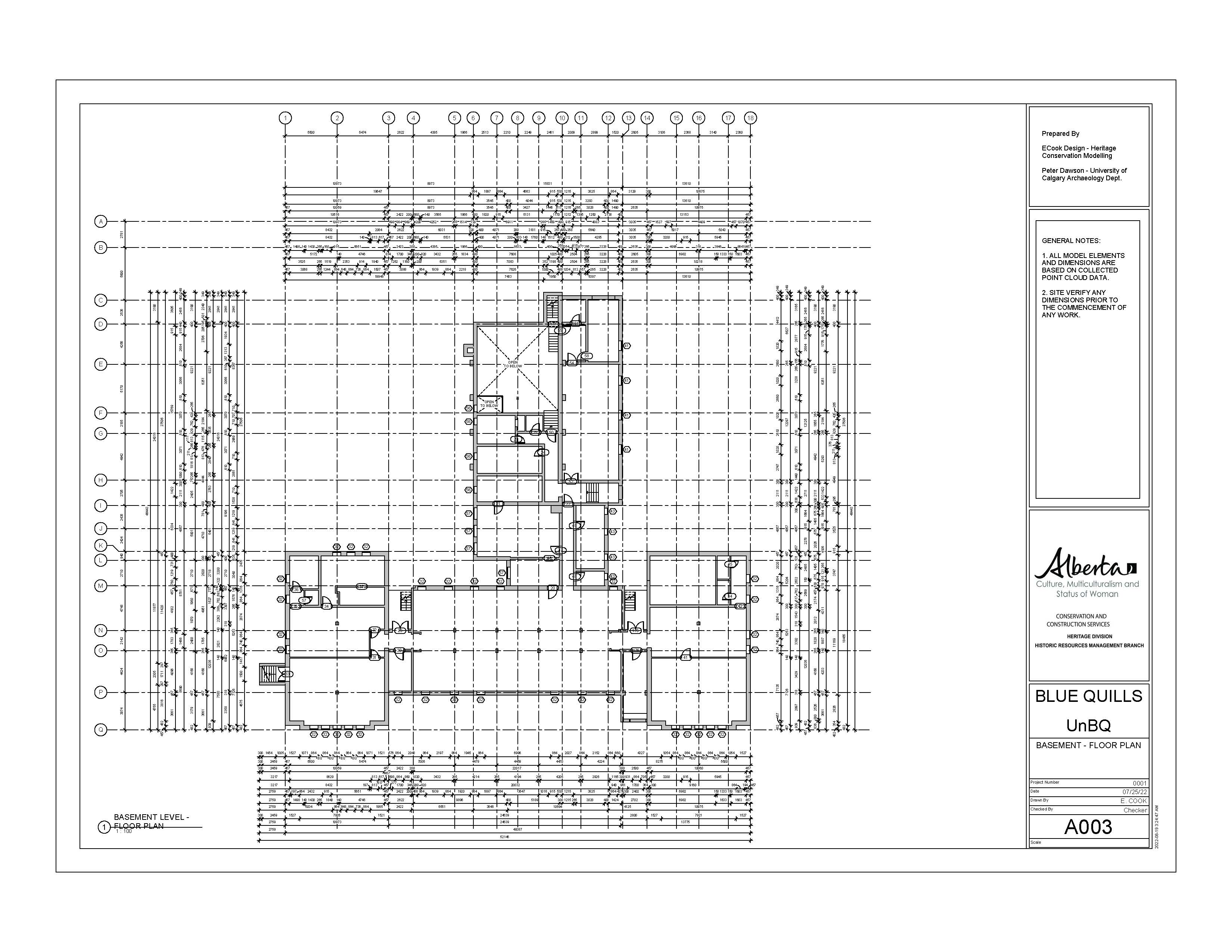

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee.

Some of the threats faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans contained in this archive, which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. There were three specific areas that placed the health and safety of students at great risk: Fire Hazards and Protection Measures; Water Quality, and Sanitation and Hygiene. As you explore the archive, you will find more information about the nature of these hazards and their impact on students.

The other incident that happened in boarding school, was my little brother, he’s two years younger than me, he came to boarding school and he didn’t stay more than two. Two weeks, he ended up in the hospital because the nun there, she’s probably gone now, but her name was sister Jubeir, she ripped half my sister- my brother- my brother’s ear off, because my brother was… He just didn’t want to be there. He didn’t want to stay there, and he protested so much that his ear, he wanted to run so much that the nun ripped his ear.

I said to my brother when he was older, that he should claim this, and he said no, he said he wanted to forget it, and he did get the first payment. He said “I only stayed there a week and a half.” and I said, I said to him, “You suffered a week and a half.”

My older brother was there. One valentines, I made him a Be My Valentine card and I discreetly, at lunchtime, gave it to him. I didn’t realize we, we, got caught, and he suffered quite a bit, and I did too because I was made to feel that what I did was very dirty. That, you know, that was just… it was disgusting, that I dared to touch my brother, and be touched by a man. I never saw my brother for two weeks, because the only time we could see each other was when we went downstairs to the, to the, where we had lunch, at the cafeteria.

I spent a lot of time in the chapel when I was young, and a lot of time in the stairwell because the nun’s didn’t know what to do with me. When I was five, I had polio, I got polio in the hospital. So therefore, I couldn’t go skating, I couldn’t go do things that most of the kids could do at boarding school.

So I had to spend my time in the chapel because the nun said that I deserved the wickedness that I had in my life and that’s how I’m paying for it and that I had to spend it in the chapel. And if they couldn’t put me in the chapel, I was put in the stairwell.

– Margaret Cardinal

Margaret Cardinal Testimony. SP118_part16. Shared at Slave Lake Hearing Sharing Panel. June 18, 2013. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SP118_part16

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read more

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more