UnBQ Boiler Room

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

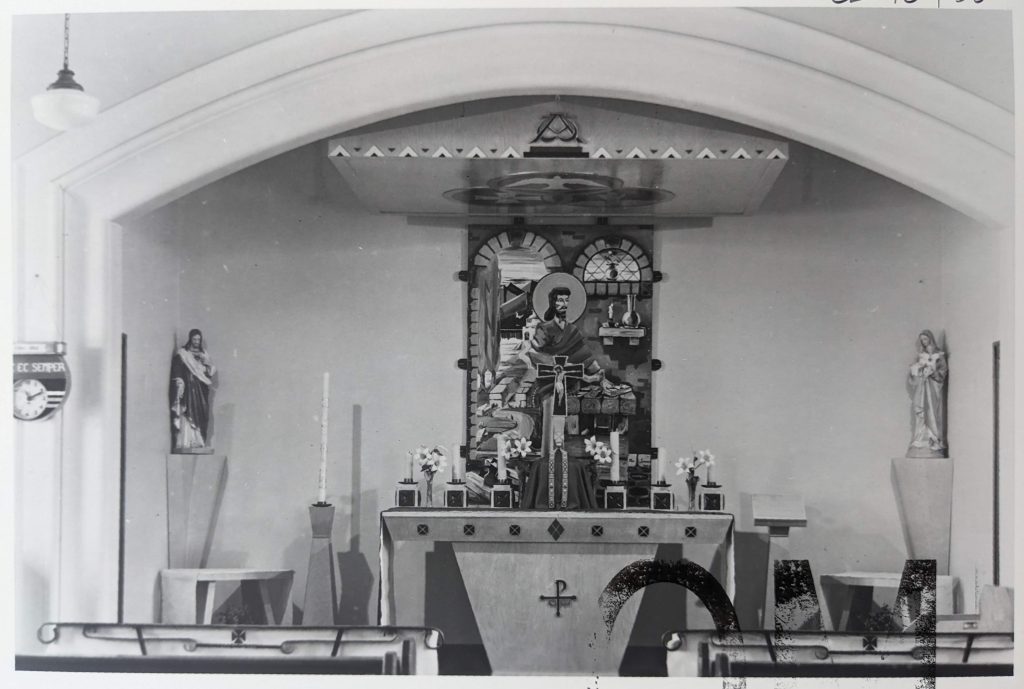

Read moreThe Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). This Important area originally served as the chapel at Blue Quills Indian Residential School. The chapel features prominently in the architecture of the school, as well as the lives of the children and community members who attended services here. Click on th

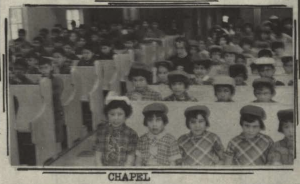

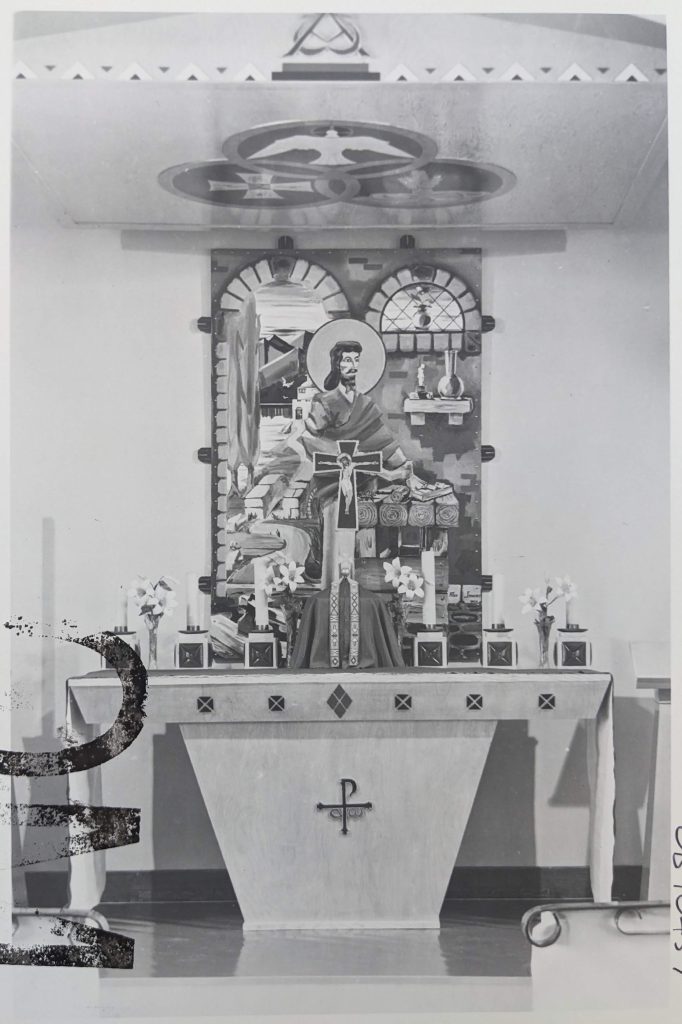

The current library of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills once served as the school chapel. A multi-level addition to the library completed during the 1960’s now provides more shelving for books. What was once the chapel, is now dedicated to the front desk, computer stations, and displays of student work.

When used as the chapel, boys and girls would be brought into the sanctuary where they would be seated on separate sides. Former students recall spending a great deal of time in the chapel. This was both for attending service and to pray, but also for punishment for being bad. As Margaret Cardinal recalls, “I had to spend my time in the chapel because the nun said that I deserved the wickedness that I had in my life and that’s how I’m paying for it and that I had to spend it in the chapel. And if they couldn’t put me in the chapel, I was put in the stairwell.” A common punishment in these schools was locking children in isolation in storage spaces, cupboards or quiet areas.

Religion was a large part of the day to day functioning of Blue Quills Residential School. Religious activities, including mass, confessional, and extracurricular religious groups, were all efforts made by the governing Catholic church to enable students to convert to Catholicism and assimilate into Euro-

Canadian culture. Students who arrived at the school unbaptized would be baptized after arrival as well as sent through the sacraments of communion and confirmation. According to the Oblate School Report of 1949, students were obligated to attend Mass the first Friday of every month but were encouraged to attend additional Masses. If students did not attend the additional Masses, they were restricted to their dorms. Confessional was held on Wednesday evenings once a month, with a student interviewed by Persson (1980:147) stating “[…] I felt very guilty about the sins I committed, and very guilty about the sins I’d committed that I’d forgotten. I felt very bad because I was always in a state of sin and I was afraid to die because I’d go straight to hell. The confessional to me was a traumatic thing.” The 1949 report also stated that the rosary was recited each evening after supper [1].

Students also participated in religious student organizations, such as the Missionary Association of Mary Immaculate (MAMI) whose goal was to encourage student involvement in mission work of the Catholic Church. Members of MAMI would conduct mission work by spending time at the missionary at Saddle Lake for male members or making and selling Bazaar items for female members, with the proceeds being sent to the churches in surrounding communities. In the earlier period of Blue Quills, students that were part of religious organizations or participated in school religious events were provided medals to wear as a sign of their faith.

A student, interviewed by Persson (1980:123), said “I think the idea about being a priest was tossed around, but as much praying as we did I never saw anyone become a priest or even a religious man in the Roman Catholic faith.” Persson (1980) noted in her work that students often recall the contrast between the teaching of the church and the actions of the religious staff, such as Nuns reciting the rosary while walking down the hall, stopping to slap a misbehaving student, and continuing with their prayers [1].

As time progressed, the power of the churched decreased during the tenure of Blue Quills Indian Residential School as more lay employees and teachers were hired and more control over the administration of the school fell to the DIA. Religion continued to be component of Blue Quills throughout but altered over time in how it was conducted.

[1] Persson, Diane Iona 1980 Blue Quills: A Case Study of Indian Residential Schooling. University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

This image gallery includes modern and archival photos of UnBQ's library.

My name is Felix Muskego from Cold Lake First Nation. Trying to recall, and go back 50 years is very difficult. It’s very hard, and I went back there many times, trying to get a glimpse, trying to understand, trying to piece together, the many lost years.

I spent 13 years in a residential school, I was taken at five years old, 1957, and I got out 1970. And during those times, the most profound feeling, is one of being lost. Brought up to be afraid to express yourself, express your humanity, on a daily basis. We were afraid to even do anything, because whether you’re right or wrong, you were punished for it. It’s always physical punishment, belittlement.

Very little praise in the school for whatever you may have done good, or whatever. To grow up as a child in a normal family, that wasn’t to be because you’re separated, even in that school. I had most of my family went there, and we were separated by age group, gender, and once in a while you got to see your brother, sister, couldn’t talk to them.

This is what we’re exposed to year after year after a year. I could not understand who gave them the right to do this to you. For many years, I struggled with that, who gave them the right to treat you this way, like a non-human being, a non-person, you know? I just, I don’t…

I guess I went there, I first got there, and they give you a number, and that’s your name. Your number was your name, and we had to go rank and order. And there again, they taught you to… to try to indoctrinate you with religion, pound in you a fear of God or whatever God’s supposed to be.

Made you pray, maybe seven times a day. Go to church every morning, whether you like it or not, on your hands and knees, on a cold cement floor to say your Catholic prayers.

– Felix Muskego

Notes:

Felix Muskego Testimony. SC149_part05. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Circle. March 29, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SC149_part05

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more