UnBQ Library

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read moreThe boiler room and former coal shoot at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). This large space continues to house the utilities used to heat this large masonry building. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud.

The boiler room is one of the areas of UnBQ where function and appearance have changed very little since its operation as a residential school. While there have been technological updates and modernization of the utilities, the boiler room retains much of its original appearance.

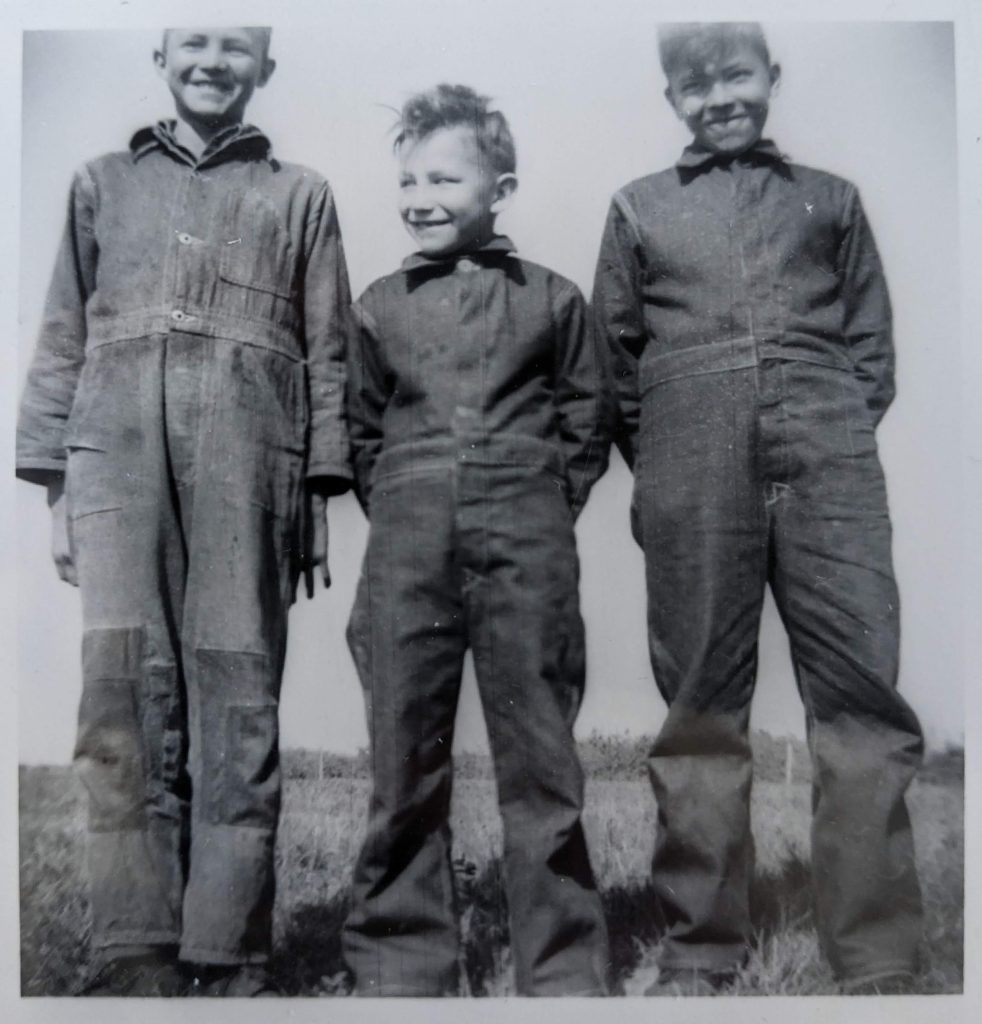

Students at the school were often responsible for tasks related to the operation of the school such as laundry, washing dishes, harvesting food from the gardens, serving staff meals, taking care of livestock, and shoveling coal. Children working at these tasks would be assigned them both as daily living chores but also occasionally as punishment.

Soon after its construction, chemical analysis of Blue Quills water supply revealed high levels saline/sodium sulfate, which is said to have a laxative effect when consumed. The extreme hardness of the water with high amounts of rust would have been harmful for both human consumption and the plumbing system itself. Despite these safety concerns, government representatives deemed the installation of a water softener to be unnecessary and too expensive.

Many of the risks faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools such as Blue Quills came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans for Blue Quills which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. In 1952, a very dangerous fire hazard was identified at Blue Quills following the construction of a new wing of the school which was accessible from two levels. Inspector F.A Ingram advised that the stairwells be enclosed so that they acted as a natural fire break to prevent the spread of fire.

The relatively remote location of Blue Quills required that fire suppression be done on site. Blue Quills had been designed to accommodate 200 students. However, a feasibility study showed that well water productivity was only able to support 100 students. This was inadequate for both fire protection and student use (hygiene and consumption). As a result, water tanks at the school were of a size that was inadequate for extinguishing any fires that might occur. Fire escapes, as seen in the virtual 3D model of UnBQ above, were also documented as being inaccessible to many students. Inspectors report that while fire escapes were accessible to students on the first floor, they were inaccessible to students on the second floor.

This image includes modern images of the boiler room. If anyone has historic photos of the boiler room at Old Sun that they would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com or submit through "Submit your Memories" button at the top of the page.

My name is Felix Muskego from Cold Lake First Nation. Trying to recall, and go back 50 years is very difficult. It’s very hard, and I went back there many times, trying to get a glimpse, trying to understand, trying to piece together, the many lost years.

I spent 13 years in a residential school, I was taken at five years old, 1957, and I got out 1970. And during those times, the most profound feeling, is one of being lost. Brought up to be afraid to express yourself, express your humanity, on a daily basis. We were afraid to even do anything, because whether you’re right or wrong, you were punished for it. It’s always physical punishment, belittlement.

Very little praise in the school for whatever you may have done good, or whatever. To grow up as a child in a normal family, that wasn’t to be because you’re separated, even in that school. I had most of my family went there, and we were separated by age group, gender, and once in a while you got to see your brother, sister, couldn’t talk to them.

This is what we’re exposed to year after year after a year. I could not understand who gave them the right to do this to you. For many years, I struggled with that, who gave them the right to treat you this way, like a non-human being, a non-person, you know? I just, I don’t…

I guess I went there, I first got there, and they give you a number, and that’s your name. Your number was your name, and we had to go rank and order. And there again, they taught you to… to try to indoctrinate you with religion, pound in you a fear of God or whatever God’s supposed to be.

Made you pray, maybe seven times a day. Go to church every morning, whether you like it or not, on your hands and knees, on a cold cement floor to say your Catholic prayers.

– Felix Muskego

Notes:

Felix Muskego Testimony. SC149_part05. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Circle. March 29, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SC149_part05

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more