Carriage House Fourth Floor

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read moreThe Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. The Carriage House Functioned as a Storage Area, Classroom, and Dormitory for the Edmonton Indian Residential School. The Carriage House All that Remains of the School following its Destruction by Fire in 2000. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud.

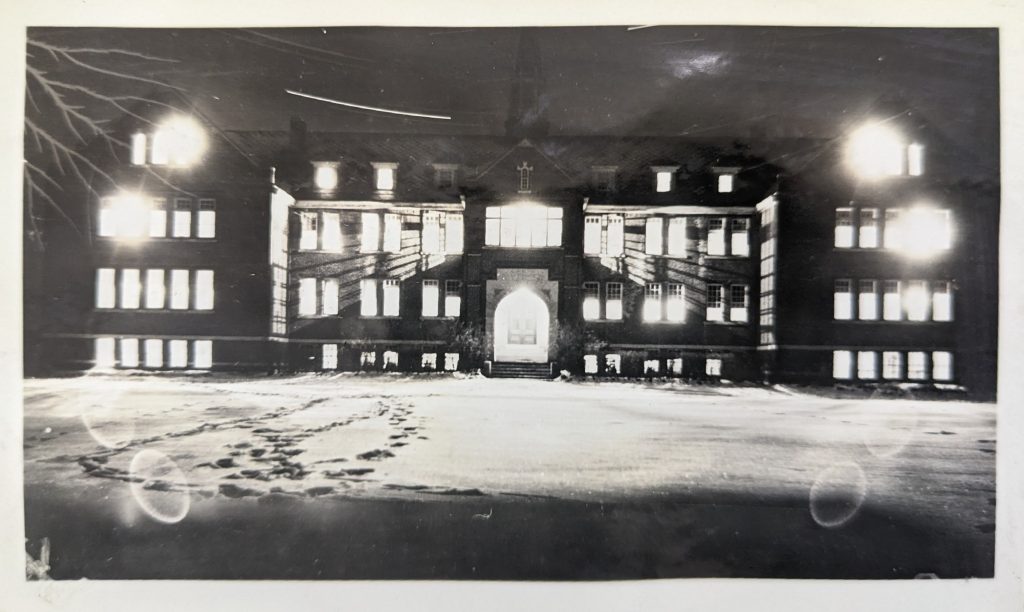

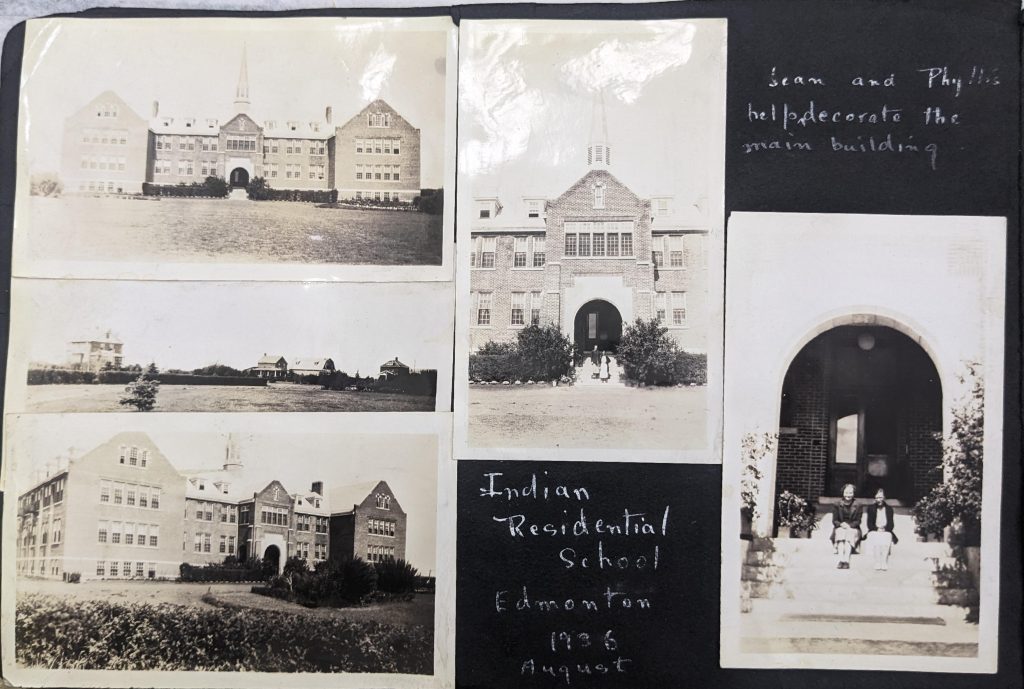

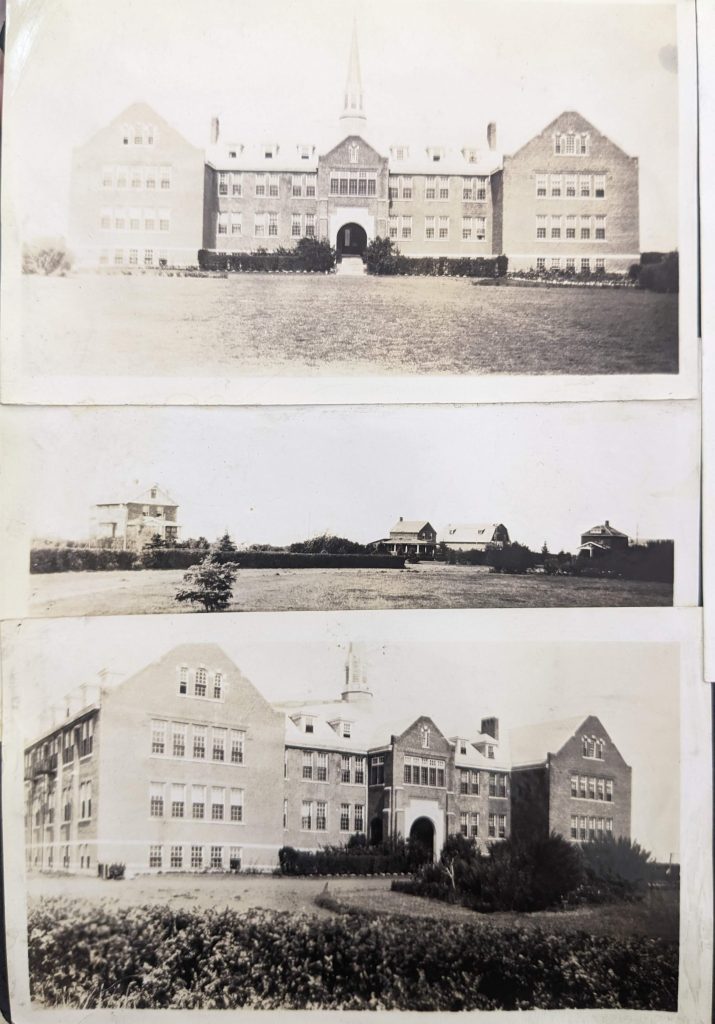

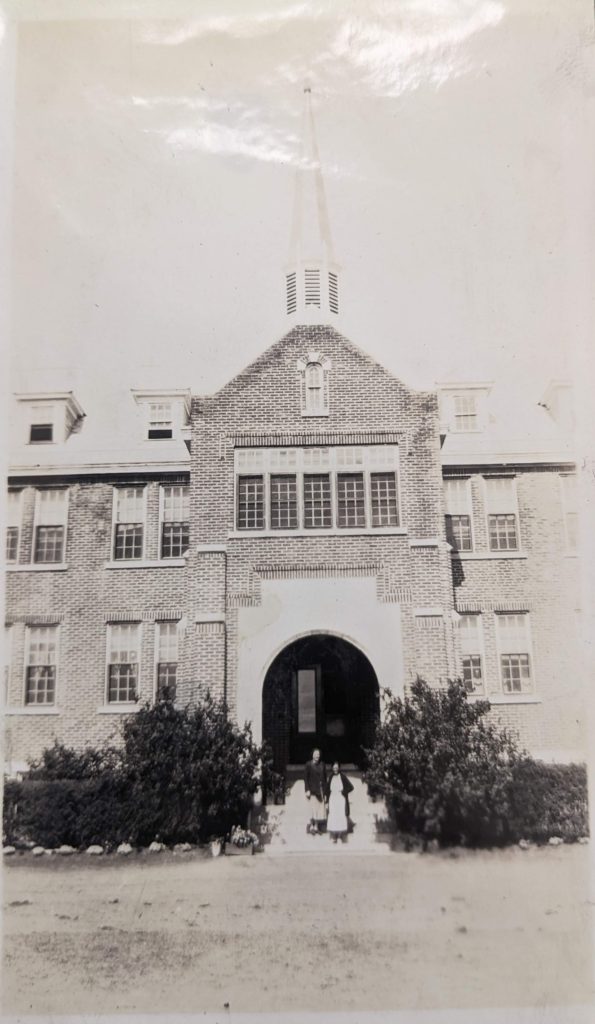

This carriage house was an axillary building of the Edmonton Indian Residential School (IRS) located in St. Albert, Alberta. It is the last still-standing portion of the Edmonton IRS, which officially opened in 1924 as a Methodist school primarily for Cree children from Treaty 6 communities [1]. However, its location along a Canada Pacific Railway line and near major Albertan highways allowed for children to be brought to the school from further reaching locations to fill its capacity throughout the years of its operation. Students were brought from throughout Alberta and areas throughout BC including from around Bella Coola, Terrace, and the Queen Charlotte Islands, and from as far north as the Northwestern Territories [1]. The school was closed in 1968, and in 2000 the main building was destroyed by arson [2]. Visiting the Edmonton IRS on the day after it was burnt, Jean Aquash a former residential school student, said “I’d never been so happy in my whole life” upon seeing the building destroyed [2].

Poundmaker’s Lodge and Treatment Centre operated out of the main Edmonton IRS building from 1975 to 1984 when they relocated to a new building on site. Poundmaker’s is Canada’s first addition treatment centre specifically for Indigenous clients and still operates in the 1984 building on site [3]. The only portion of the original residential school that is still standing is the carriage house, which is located just north of where the main school building would have been.

When the Edmonton IRS was functioning, the landscape surrounding Poundmaker’s Lodge and the carriage house would have been much different. There would have been outbuildings, like a barn, at various times as well as a sports field and a hockey rink in the winter. Fencing was also an integral part of the structure of the residential school infrastructure, most often used to keep children imprisoned at the school [4]. When discussing the type of high fencing to install around the girls’ playground at EIRS, Principal Woodsworth opted for a high page wire because it would not “be too much like a prison” [4, 5].

Residential School Survivor Isabell Muldoe of Gitxsan First Nation described her experience when she arrived at EIRS:

We got off in front of the school, we looked up at this big building. It was huge because we were little then. It was a huge building. You’ve seen pictures out there. And to us, it was like we walked in there, and we were just literally swallowed up in these buildings. We got swallowed up, and for the girls that’s where we stayed. The boys were more, they had more freedom than we did. They were able to wander around in the fields and the bushes and whatever. But we were fenced in like a bunch of cows. We were not allowed to go beyond the wired fences, and they were wired fences. If we were caught outside those fences we were punished severely, strapped. Or else you had to do extra work, as your, along with your monthly duties. [5]

With their use of barbed-wire fencing, the physical spaces echoed of prisons or cattle ranches to both the principal and the students, thus imposing a physical manifestation of the children’s entrapment and their helplessness [4].

Fire safety issues plagued Edmonton Indian Residential School. Fires often started in areas like the laundry room and utility/boiler rooms in the basement of the main EIRS building. Investigations reveal that the causes were often due to faulty wiring. Once a fire started there was often little that could be done to suppress or prevent it from spreading because of inadequate supplies of water. In May, 1925, a fire which started in the laundry room spread quickly, damaging the school chapel one level above. Recommendations resulting from this incident included the digging of a second well to provide water for such emergencies. Five years later, a report commissioned by Deputy Super Intendant Duncan Campbell Scott from the Dominion Water Supply concluded that the costs associated with a second well were too high.

A second laundry room fire occurred in October, 1948 causing significant damage to the basement. Holes needed to be cut into upper floors and roof I order to help extinguish the fire. Fire poles were used at EIRS to facilitate escape from blazes. However, reports indicate that the poles were too short/too high off the ground for students to use without risk of significant injury. Regardless, these fire poles remained in place twelve years after this issue was first reported.

As with Old Sun, locked doors in staff areas often meant that fire routes were inaccessible. When estimates for replacing these doors were presented to solve the problem they were dismissed as “entirely out of proportion to the additional protection” they would provide to students. The fire poles were eventually replaced with stairways externally fitted to the building. However, fire alarms which would have warned students about a potential fire risk were not installed.

For a more immersive virtual tour by Denis Gadbois, please click here: PoundMaker | Virtual tour generated by Denis Gadbois (ucalgary.ca)

[1] United Church of Canada. 2022. Edmonton Indian Residential School. The Children Remembered. Electronic document, https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-histories/edmonton/, accessed February 23, 2022.

[2] Ma, K. 2018. The Red Road of Healing. St. Albert Today 13 July. Electronic document, https://www.stalberttoday.ca/local-news/the-red-road-of-healing-1299235, accessed on August 3, 2022.

[3] Poundmaker’s Lodge and Treatment Centre (PLTC). 2022. About. Electronic document, https://poundmakerslodge.ca/about/, accessed August 29, 2022.

[4] Wallace, R. and N. Pietrzykowski. 2022. Digital IRS Archival Research Unpublished report prepared by Collective Heritage Consulting for P. Dawson, University of Calgary. On file in Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

[5] Department of Indian Affairs (1919-1937). Edmonton Agency – Edmonton Industrial School – Administration [administrative records]. Headquarters central registry system: School files series (RG10, Volume 6350, Reel C-8706). Library and Archives Canada. Ottawa.

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

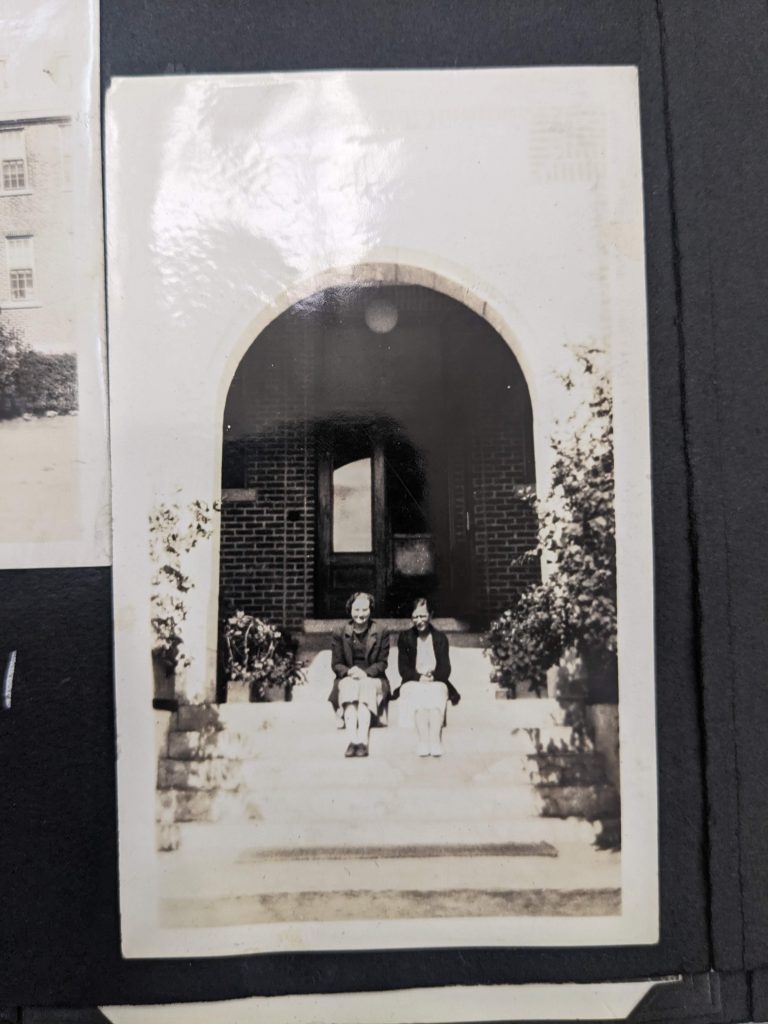

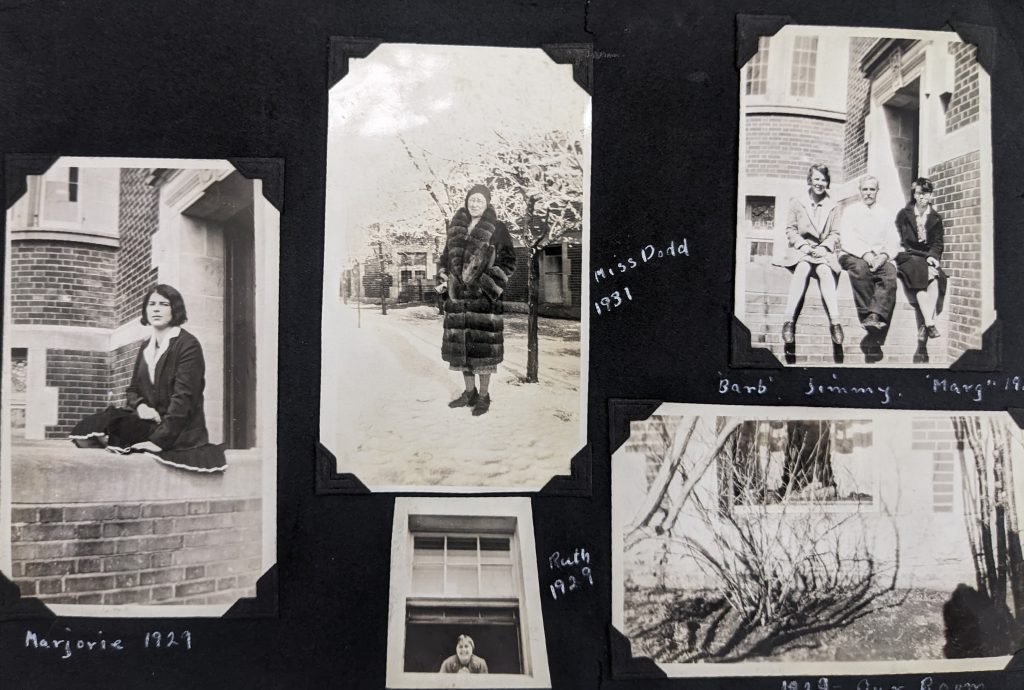

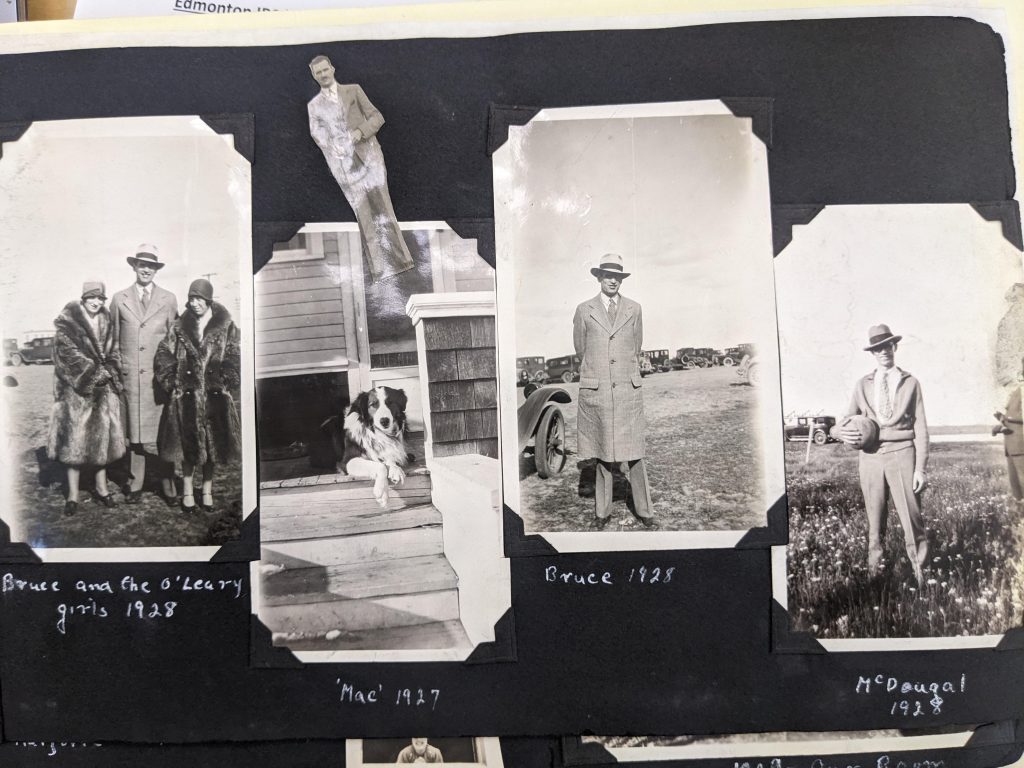

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

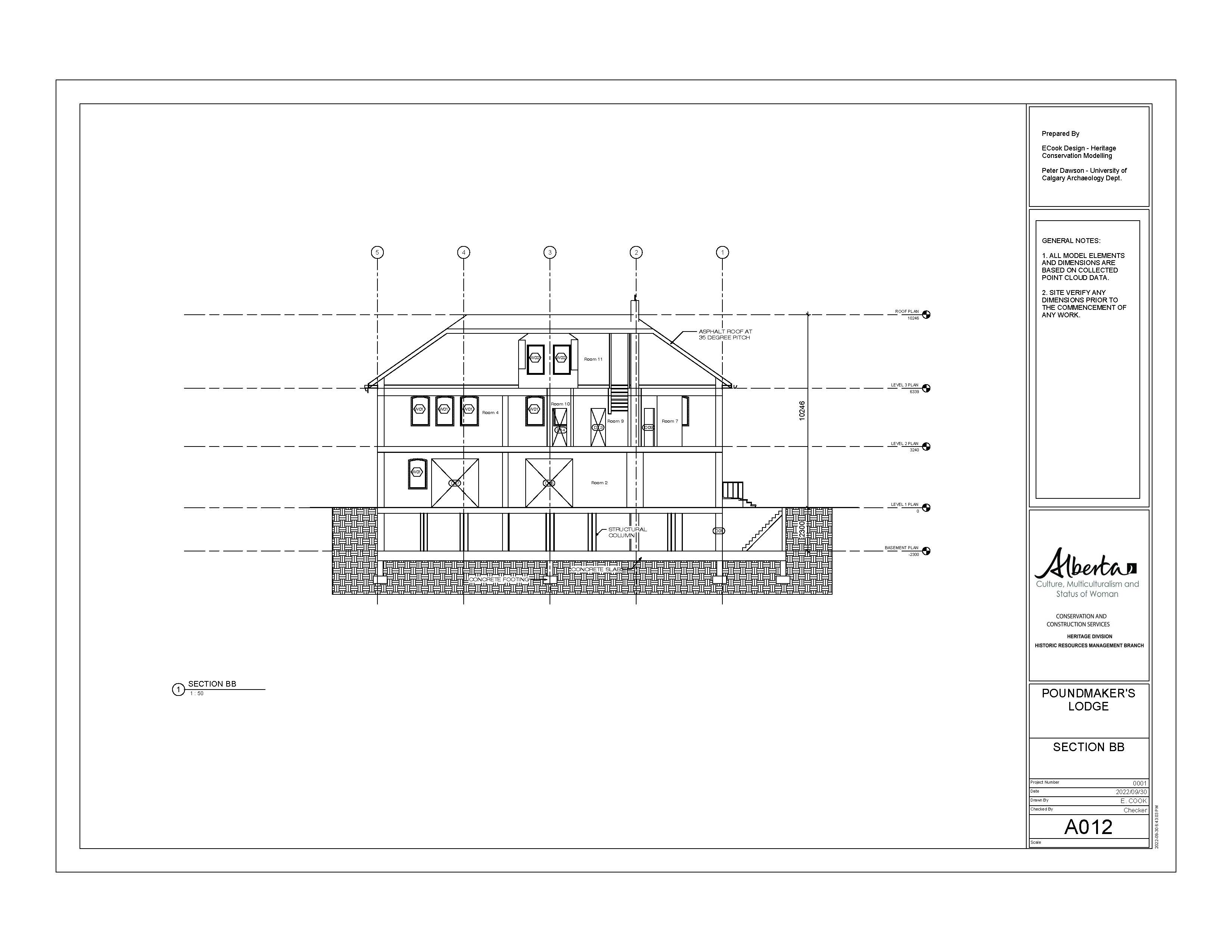

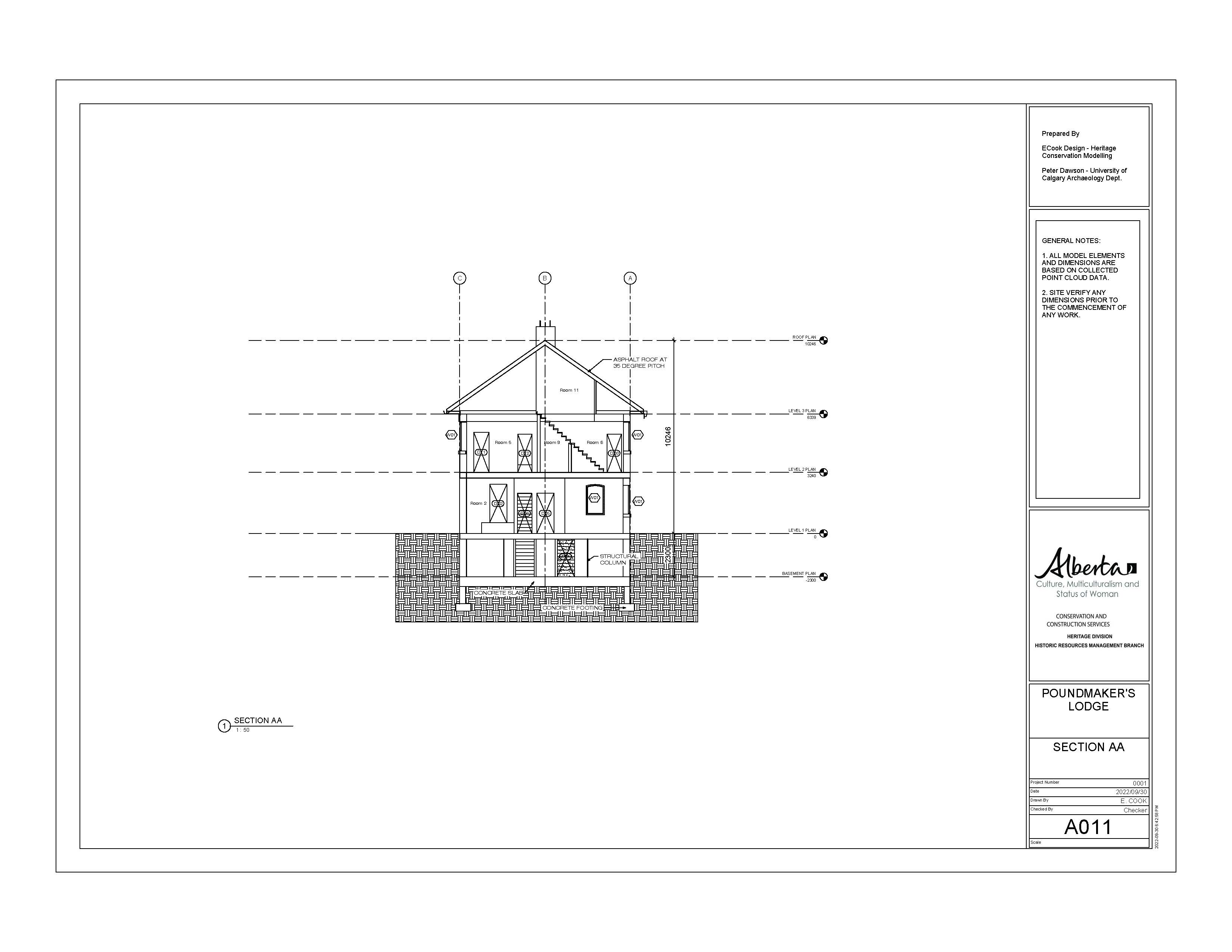

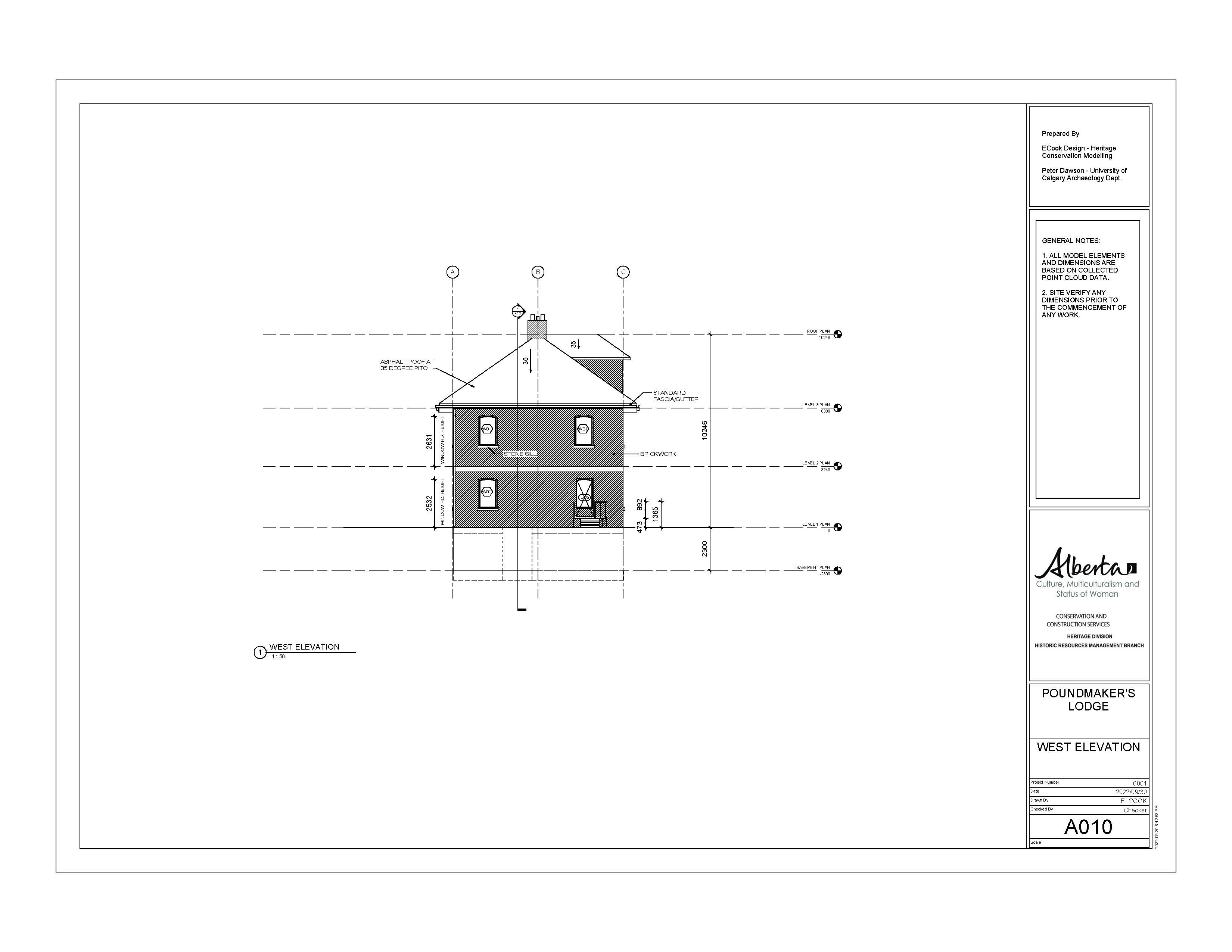

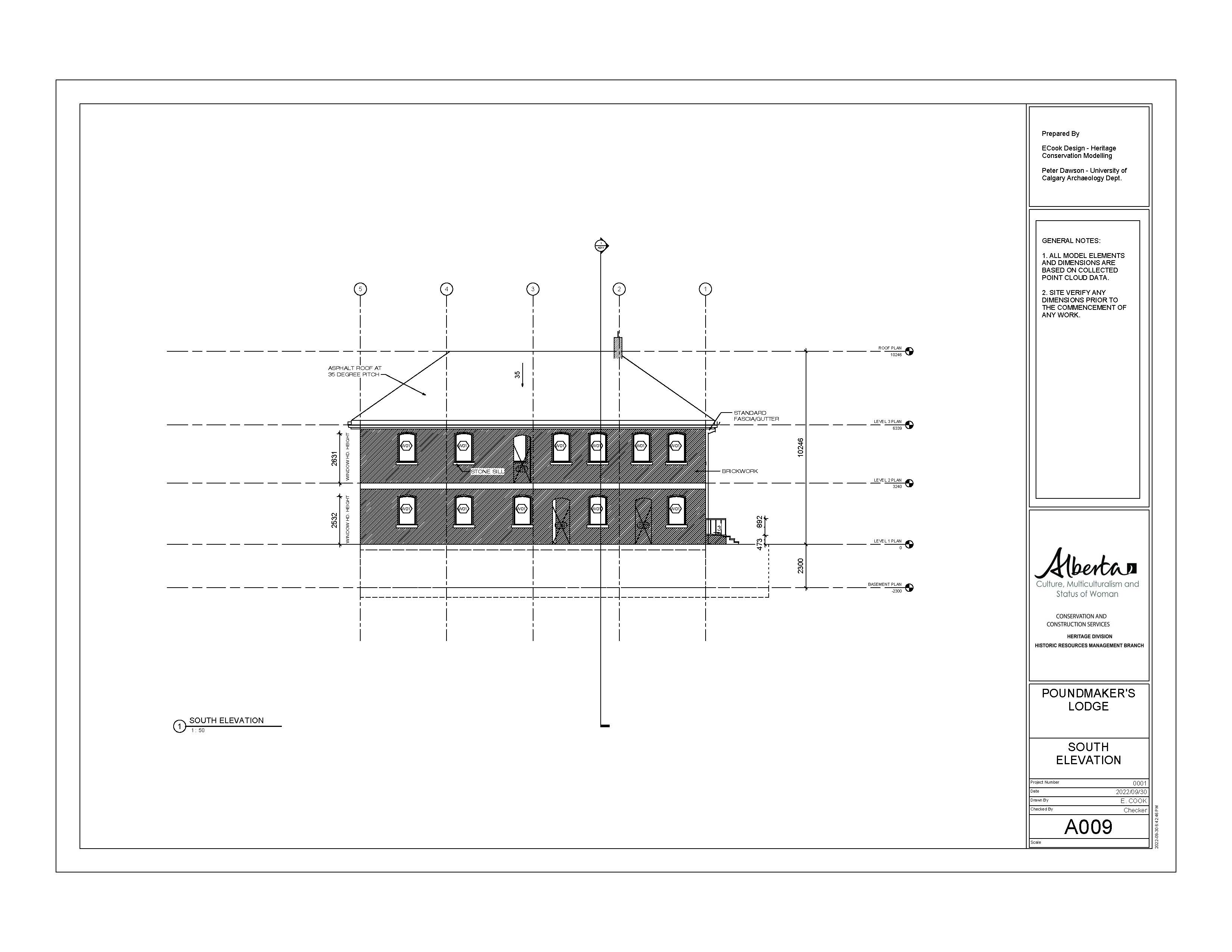

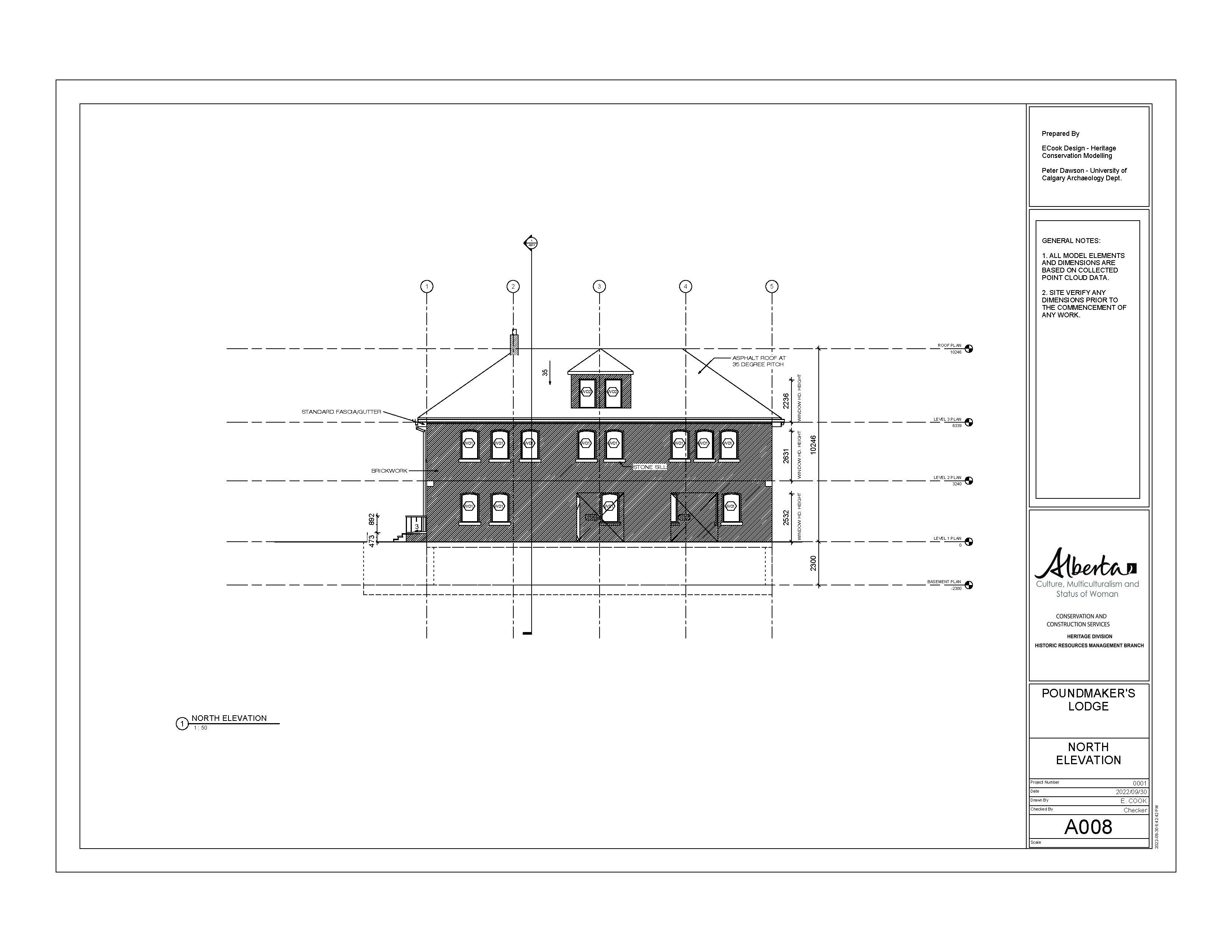

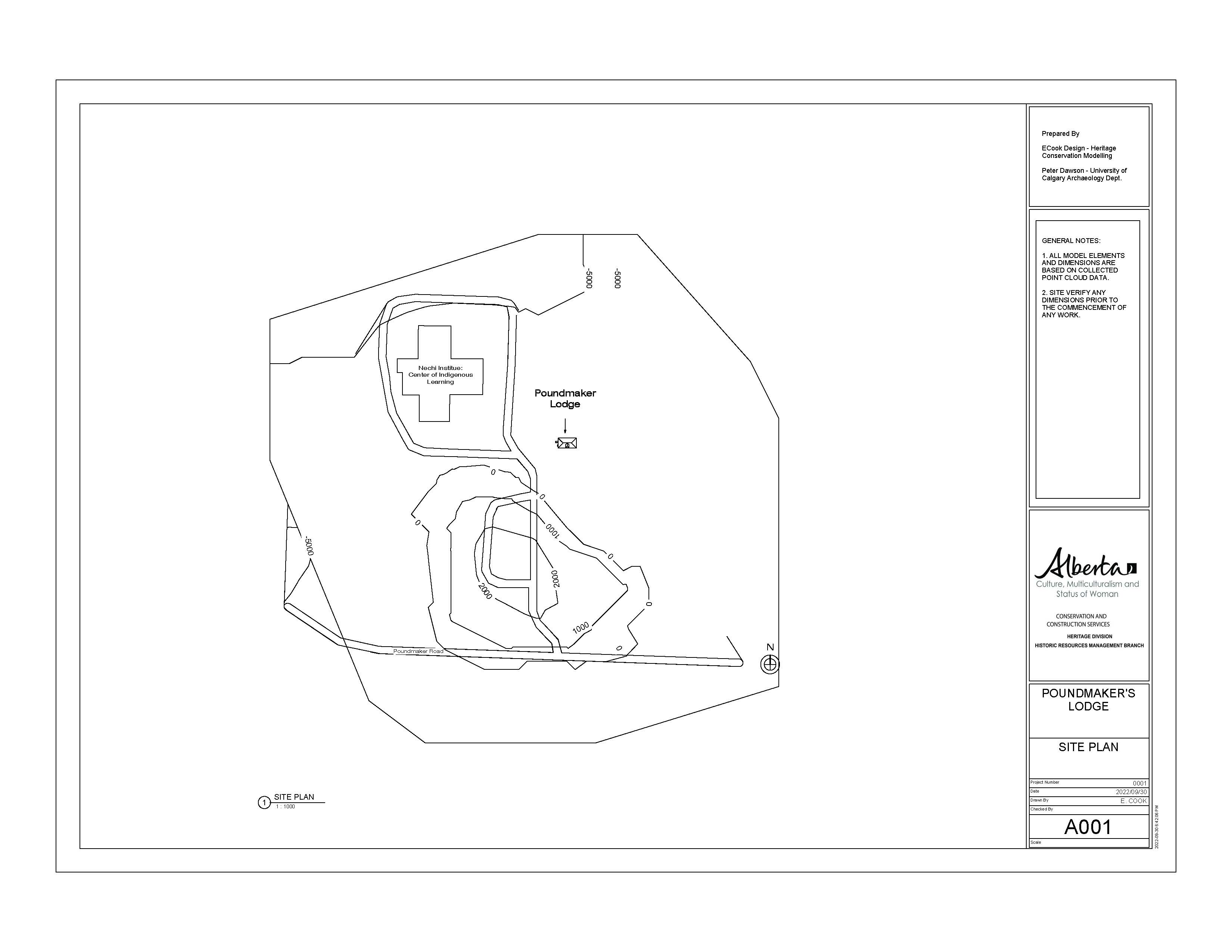

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

They gave us a set of pajamas tops and bottoms, and our clothes were left, or they were gone. We don’t know where they went to, destroyed, burned probably. Gave us a set of blankets, bottom and the top blanket and showed us to our dorm. When we got to the dorm there was about, maybe 25-30 beds in there, single beds, steel frame braided beds. There was no bunks at that time. It was just single beds, and I picked my corner there, close to the bathroom and to the showers there. There they had showers, and so we… [background interruption].

They made us stay on our beds, or beside our beds. So it was time for a snack before lunch or dinner, and we did have our lunch, and you’re sitting there not knowing anybody.. or the other 25 people or whatever. And we waited for lunch because we travelled a long way and we were quite hungry at that time. We had our lunch and then they hauled us into a dorm and all together, sort of get together meeting about the rules and everything.

“This is your dorm and your number,” and so and, “this is where you reside until we tell you to move.”

Anyway, we got we got our instruction orders; no swearing, no talking your language. All that sort of thing.

-Gary Williams

Oral interview with Gary Williams. Conducted by Peter Dawson at Poundmaker’s Lodge, St Albert, May 4, 2022. Transcribed by Erica Van Vugt and Madisen Hvidberg. University of Calgary, Jan 23, 2024.

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read more

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more