Carriage House Third Floor

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read moreThe Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. This Space Originally Served as a Dormitory and Infirmary for the Edmonton Indian Residential School. It is Notable for the Large Amount of Children’s Graffiti Found on Various Walls. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room function

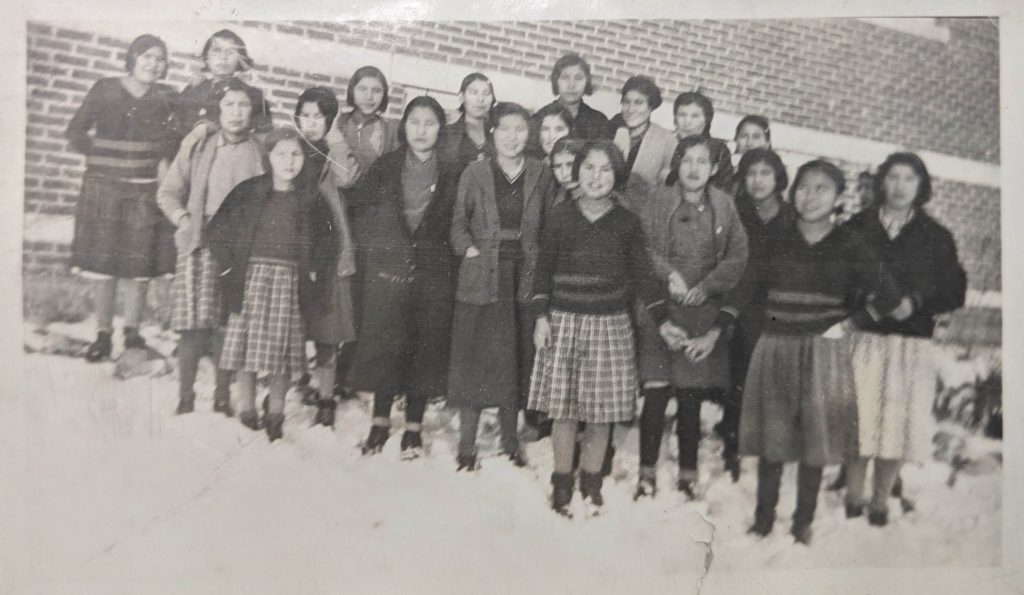

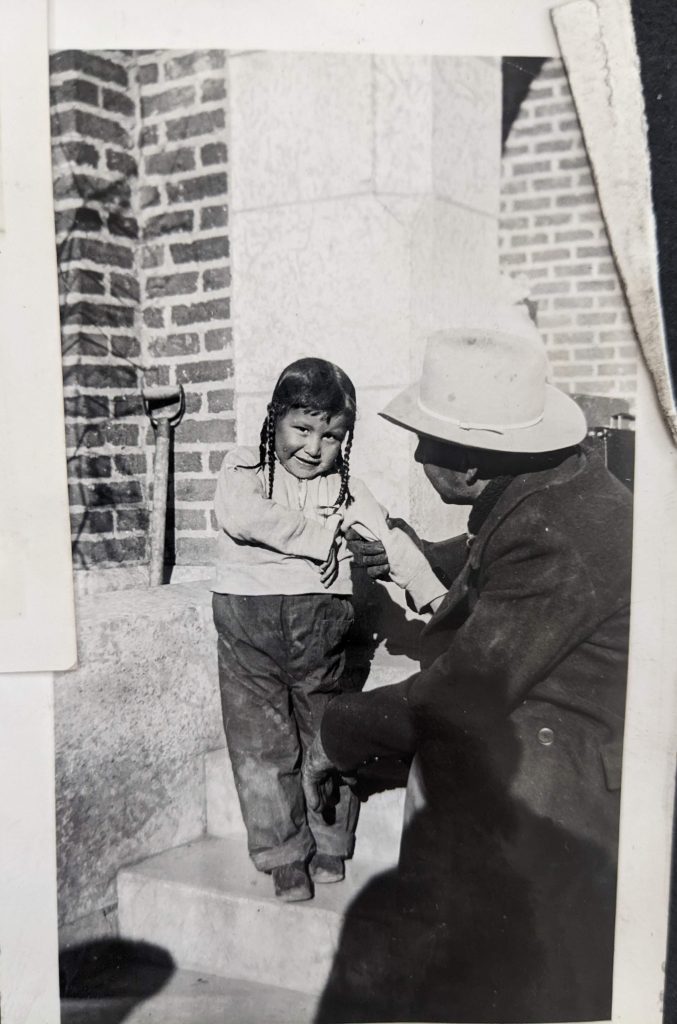

The third floor of the carriage house, which is an uninsulated attic, was used as extra room space for students. At different times, it was used as an infirmary to house sick students or as a dormitory for students who were about to leave the school. Emptied of the beds with their thin mattresses, this unfinished attic is left covered with pencilled on graffiti from former students. Some of these pieces date as far back as the 1930s, and many are from times during the Christmas holidays. Children were not only spending the break at the school, but winters in this room.

Students were intentionally kept apart from their families. A sense of alienation and isolation was built into the landscape of the schools which were constructed in remote locations, off-reserve, and frequently along unfinished roads. The school administration conveyed their frustration with being so alienated from towns and villages in various correspondence over the years. For example, more than two decades after it was constructed, Principal Woodsworth complained that EIRS remained nearly inaccessible as the road conditions made it “practically impossible” to move between school and the city after a decade of heated correspondence on the issue.

Due to respect out of family and community members of the former students who wrote their name here, we have omitted photos of graffiti from the public archive. These have, however, been photographed and preserved with this project. Community members interested may contact the Poundmaker’s IRS Advisory group via email.

Sanitation issues occurred at EIRS soon after opening. Water pressure was too low to allow toilets to properly flush. For a period of two weeks in 1924, students and staff had to carry pails of water into the bathroom in order to flush the toilets properly. Water pressure issues also prevented the use of laundry facilities during this period. A recommendation made to change the water tank system to address the issue was rejected by government officials because of the associated financial costs.

During an inspection seven years later, the boys’ washrooms were deemed unfit for use because of serious sewage backups caused by gravel in the septic tank which had clogged the syphon used to empty the tank. These problems stem from the fact that the septic system was poorly designed, resulting in sewage passing too quickly through the tanks and emptying into a pond roughly 100 yards from a barn, and 300 yards from the school. This resulted in frequent drain back ups – sometimes as many as four times in 15 months. Inspection reports indicate that septic system failure was a constant problem for 25 years at EIRS – yet at no time were long term repairs ever undertaken.

Residential school Survivors often speak of chronic medical conditions caused by attending residential school, the most common of which is respiratory illness or damage. All three schools had issues with dust particles from the unsealed cement floors and long histories of water seeping through walls, roofs and ceilings – often for months or longer – without being addressed. In the case of BQ IRS the school opened to students shortly after being built near St. Paul without having sealed its flooring. At his first inspection of the BQ IRS in August 1932, Inspector of Indian Agencies M. Christianson focused a great deal on the floors noting that dust rose continually off the floors, leaving dust particles in the air throughout the building.

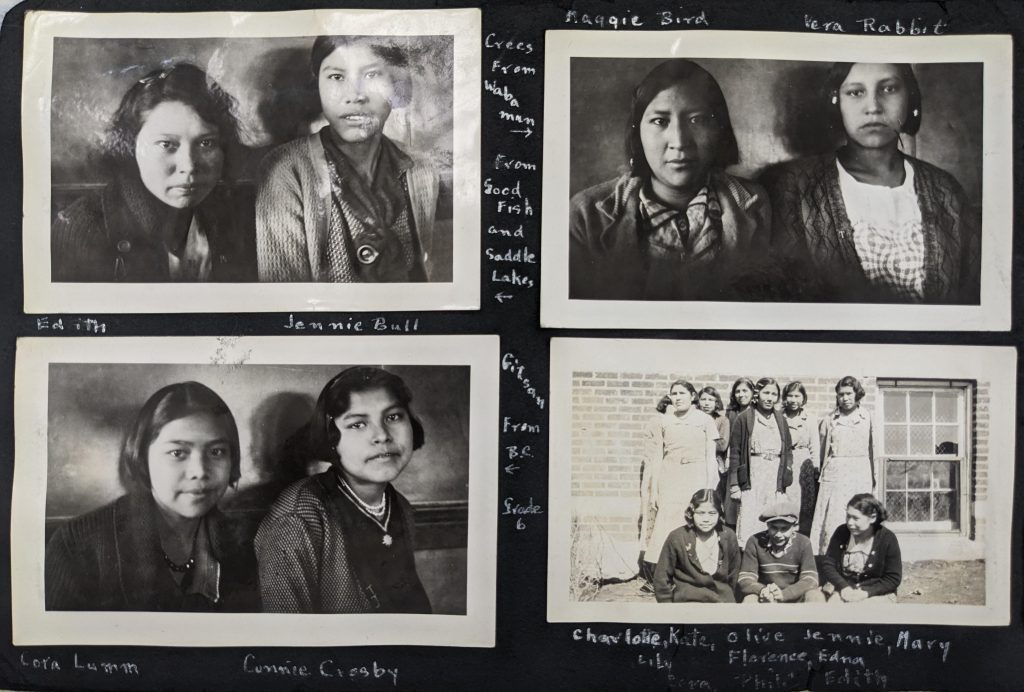

The Department of Indian Affairs was so committed to keeping students in the IRS that when a school with enrolled students needed to close or if a region had more First Nations youth than spaces at their local IRS, students would be shuttled across provinces. EIRS had students registered who came from as far away as Terrace Indian Agency in British Columbia (more than 1,300 kilometres away), and in 1929, the DIA transferred 83 students from an IRS in Brandon, Manitoba (1200 kilometers away) because that school was closed for one year (Edmonton Agency, Vol. 6350, Reel C-8707, 1929).

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

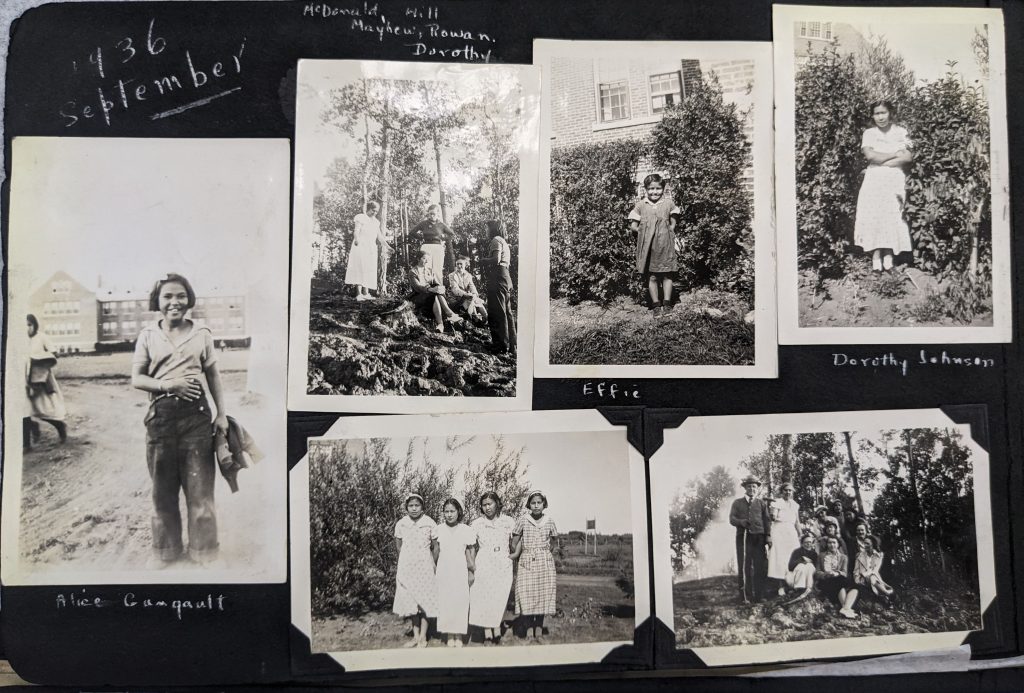

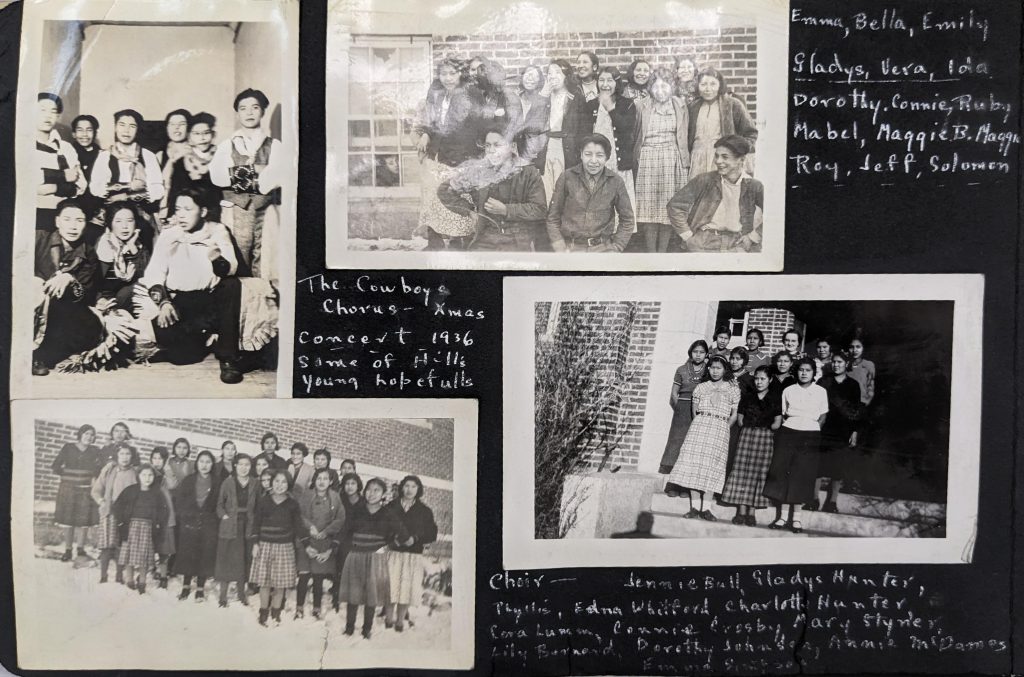

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos related to the third floor of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

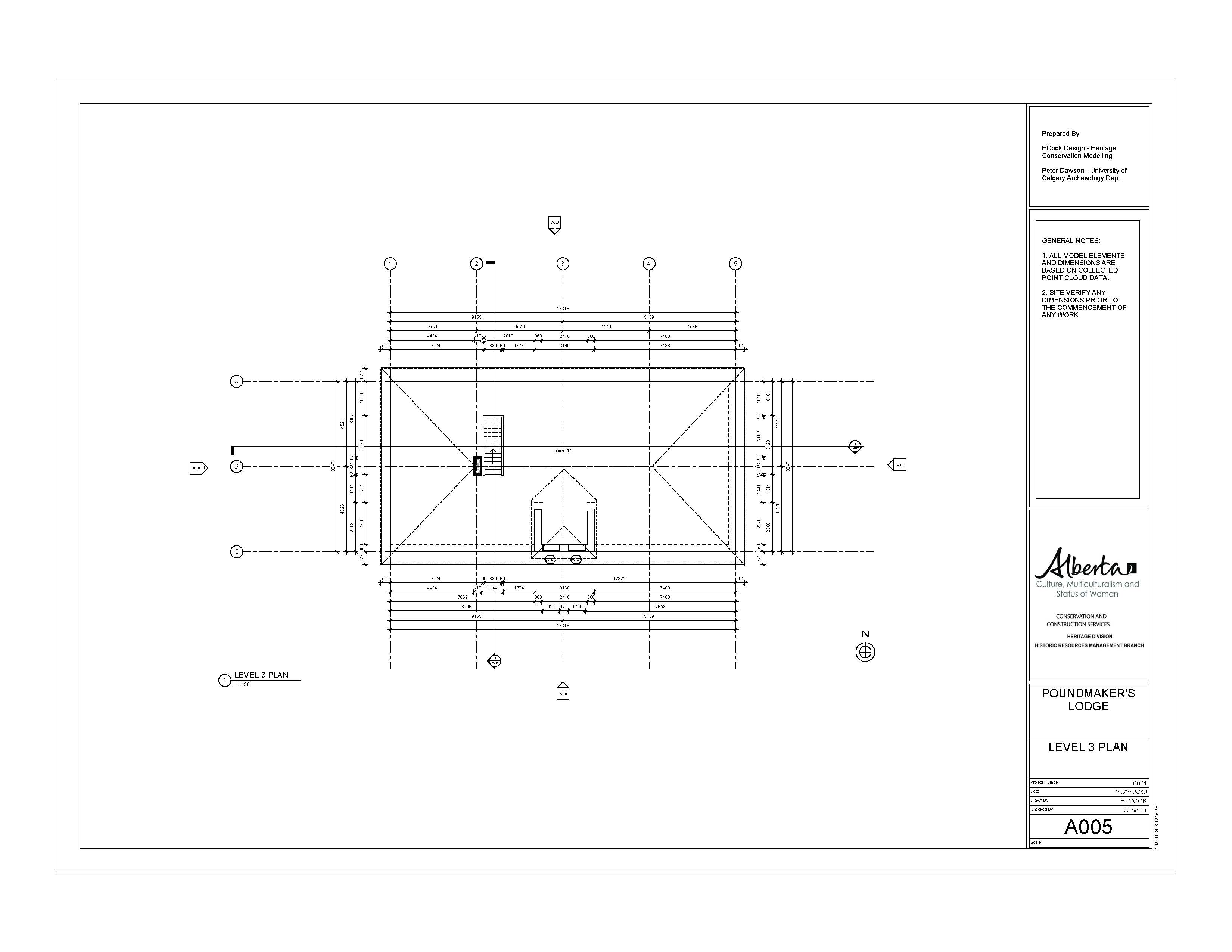

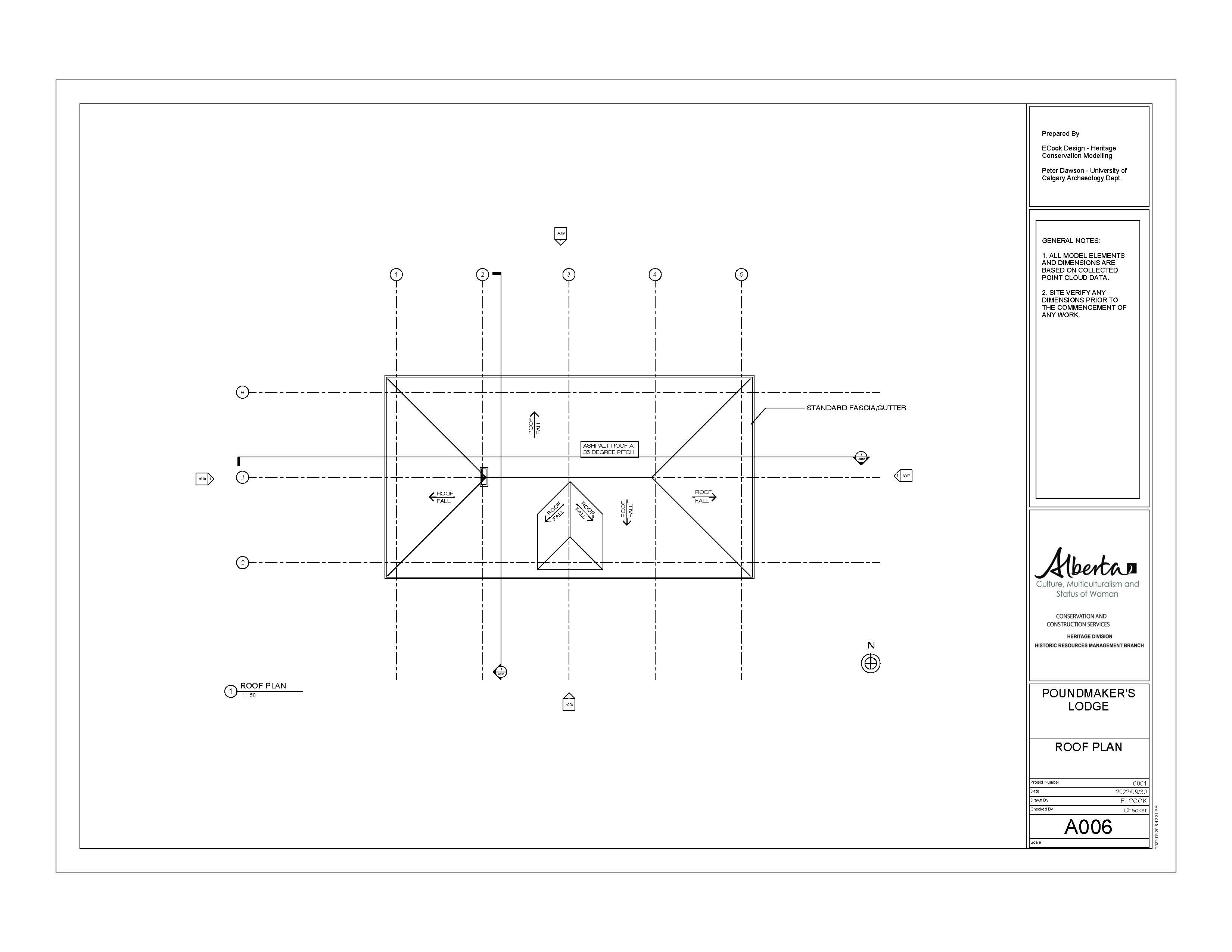

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

Okay. Hey, it’s Gary Williams here. Survivor of the Edmonton Indian residential school. We were, I come from the land of the Gitxsan people in Northwestern British Columbia. I was born in 1949, and about in 1961, my brother and I, Wilfred he’s two years younger than me, arrived here by train. And we didn’t know where we’re going.

Our Parents didn’t let us know where we were going, they said, “Just get on,” well they didn’t say get on the train. It was, they called them Indian agents back then, the people that are working for the government that looked after the Indian reserves. And so they got us ready. Just had the clothes we had on. Get on a train. Took us a whole day, 23 hours to get here. My brother was nine years old and I was eleven. Like I said, we didn’t know where we’re going… they just told us to “get on the train,” and that was it.

We didn’t really know, at that time, we didn’t know who all the students were. They were from all native communities in the Northwest, some we probably knew. We didn’t make contact with them, yet they were on the same train, because we didn’t know them. At that time in ‘61 we hardly knew our neighbors, let alone know our, know, our people in the community.

Anyway, we arrived here, and all the people that were on the train we were, they had a couple of bus loads that brought us to the residential school here. And again, we didn’t have… that point we didn’t know where we’re going, and where we were. So they dropped us off and they let us just form a row outside school entrance of the school, and I know that day was kind of hot like in the fall but it is still warm. And we seen this big red building in front of us in our lineup, student lineup. There was all boys because we were made to go on one side of the building. The girls were on the other side of the building.

There was an administration building in between us. But they didn’t want us to get… to go into the [school] building because there was an infirmary in the front office, close to it. They told us to, “stay lined up and wait for your turn.” We had just the clothes we had on and that was the last time I’d seen my brother [younger by two years] for four months, until Christmas time.

Anyway it was kind of strange how they handled us. 1961 this was. Just like I said we didn’t know anything what was happening. We were just like, more or less treated like animals, I guess. You follow instructions, whether it was lay down or whatever. Anyway, you’re going and it was our turn to enter the infirmary. They brought us in one by one, and the first thing they did to us was to strip us down to no clothes at all.

And the next thing they did, they had a clipper. Shaved our heads, bald. The third stage was to jump into the tub. Back in those days there was no shower or anything. They uh, they wanted to try, and that was the first step of everything was to try and clean us up to go at our residence, at our dorm.

So, they I remember them after they, the last thing they did to me was to scrub me down, they had some people the workers there. I don’t know if they were guys or whatever they were. They were scrubbing us down until they were trying to make us white I guess, so after we’re done wiped ourselves dry.

-Gary Williams

Oral interview with Gary Williams. Conducted by Peter Dawson at Poundmaker’s Lodge, St Albert, May 4, 2022. Transcribed by Erica Van Vugt and Madisen Hvidberg. University of Calgary, Jan 23, 2024.

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more