Carriage House Fourth Floor

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read moreThe Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. This Floor is Presently Used as an Equipment Storage Area by the Alberta Government. It likely Served a Similar Function While Part of the Edmonton Indian Residential School. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions.

Now used for storage for Alberta Culture, the first floor of the carriage house used to be used for storing of equipment and supplies for the residential school, such as items used for labour around the grounds which was primarily conducted by students. While education was supposed to be a core goal of the residential school system, children who attended oftentimes spent a lot of their time on vocational “training” and undertaking activities for the running and maintained of the school itself. During the harvest, for example, older boys would often spend their entire day working on the farm [1]

Countless examples of the acceptance of student as labourers are peppered throughout the DIA records. When the DIA agreed to an EIRS request to build a farmer’s cottage in correspondence from May 18,1927, Deputy Superintendent Scott suggested keeping costs low by employing “as much of the school labour as possible” [1,2]

During the harvest, older boys often spent the entire day on the farm, which, by 1929, consisted of 500 acres under cultivation, including 110 acres of wheat, 125 acres of oats, and 40 acres of barley. The potato crop that year produced 3,000 bushels. By 1933, livestock consisted of 15 horses, 59 cattle (both beef and dairy), 135 pigs, 50 chickens and 25 turkeys.

Principal Woodsworth wrote of his students being pulled out of class to haul water into the school during the 10 days in April of 1929 that EIRS was without water, as well as using school labour to build a new shed in preparation for the arrival of additional students from the Brandon IRS [1,2]. Similarly, in preparation for students moving to the new school, Acting Deputy Superintendent General, A.S. Williams wrote in March of 1931 that “staff and older boys” would be responsible for setting up the furniture and supplies [4].

By 1949 it was suggested to the church that students should no longer be used for this kind of labour, but it was not until 1955 that the administration of the Edmonton IRS finally made changes that resulted in more classroom time for students.

The carriage house was used to accommodate students when there was not enough room in the main school building. Overcrowding was a consistent problem in many Indian Residential Schools. The cause appears to be two-fold. First, the per capita grant funding model used by the Department of Indian Affairs was flawed. It assigned a fixed allowance for each student registered. This funding model was the primary source of operational funds, following the construction of a school, and therefore, more students meant more money. Second, churches wanted to recruit and retain students within their denominational faith, a practice that is discussed below. Even with overcrowding, the funds did not leave enough to cover the cost of salaries, basic supplies, or food. Consequently, repairs, maintenance and capital projects were done poorly or not at all.

[1] United Church of Canada. 2022. Edmonton Indian Residential School. The Children Remembered. Electronic document, https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-histories/edmonton/, accessed February 23, 2022.

[2] Ma, K. 2018. The Red Road of Healing. St. Albert Today 13 July. Electronic document, https://www.stalberttoday.ca/local-news/the-red-road-of-healing-1299235, accessed on August 3, 2022.

[3] Poundmaker’s Lodge and Treatment Centre (PLTC). 2022. About. Electronic document, https://poundmakerslodge.ca/about/, accessed August 29, 2022.

[4] Wallace, R. and N. Pietrzykowski. 2022. Digital IRS Archival Research Unpublished report prepared by Collective Heritage Consulting for P. Dawson, University of Calgary. On file in Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

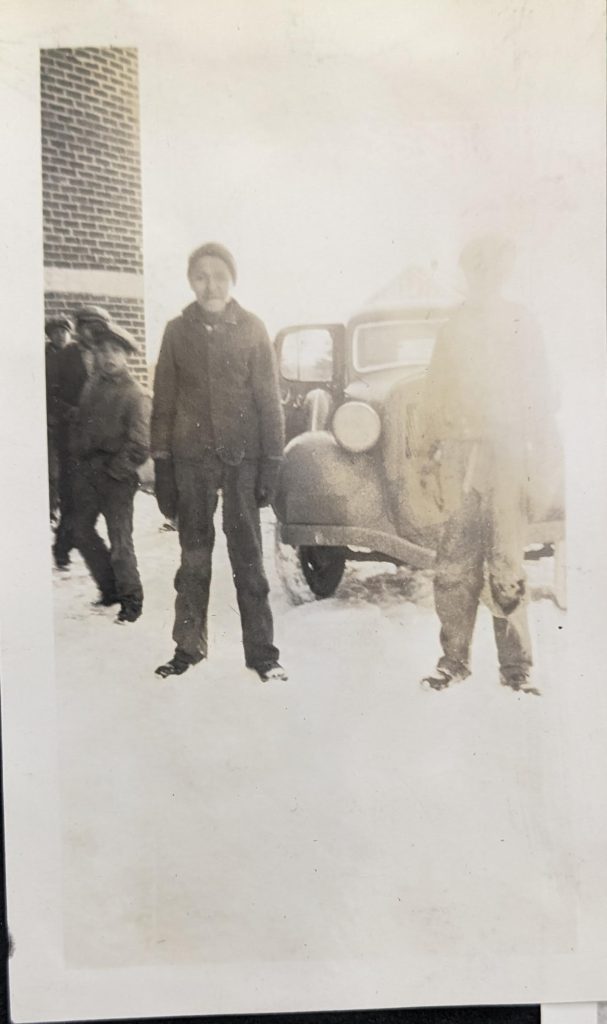

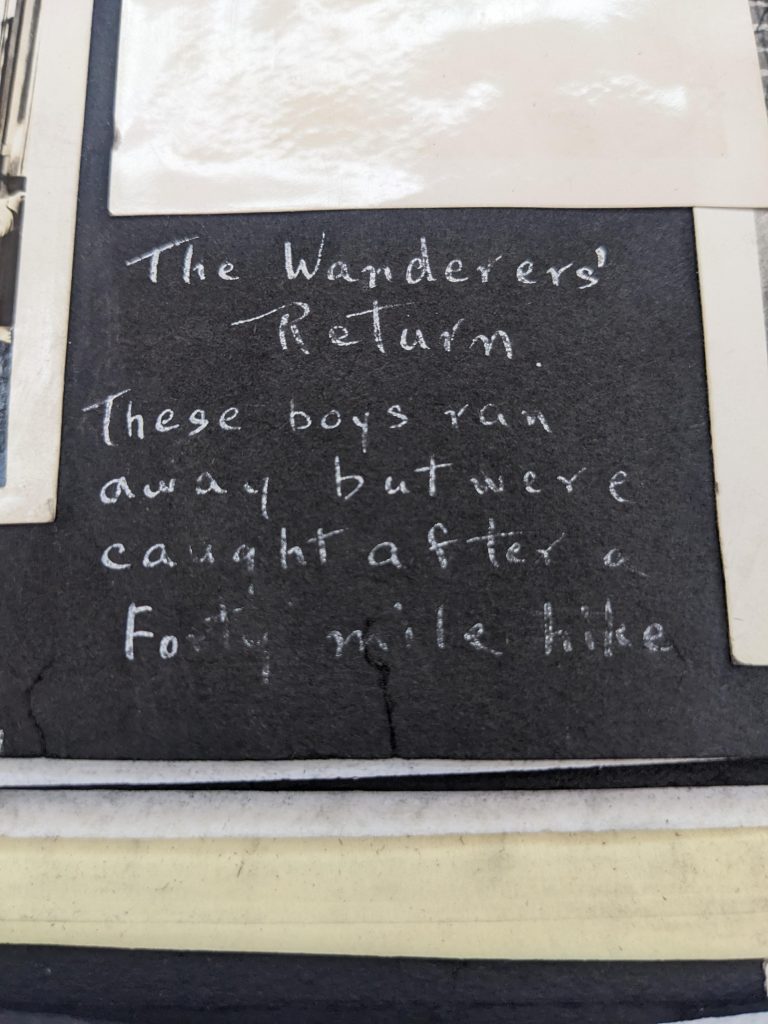

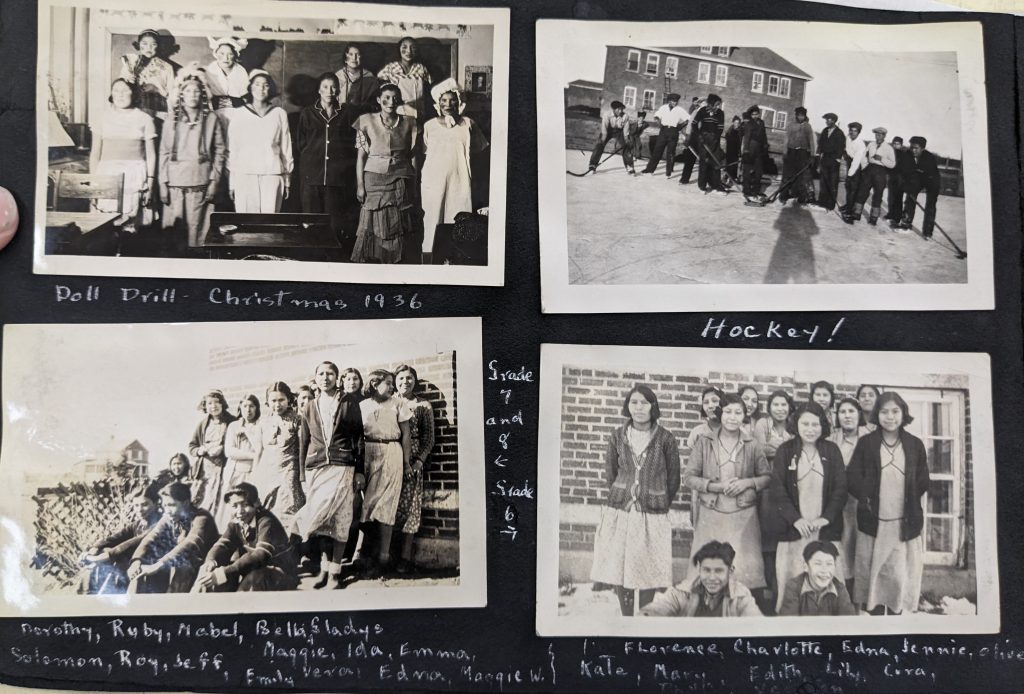

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos related to the first floor of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

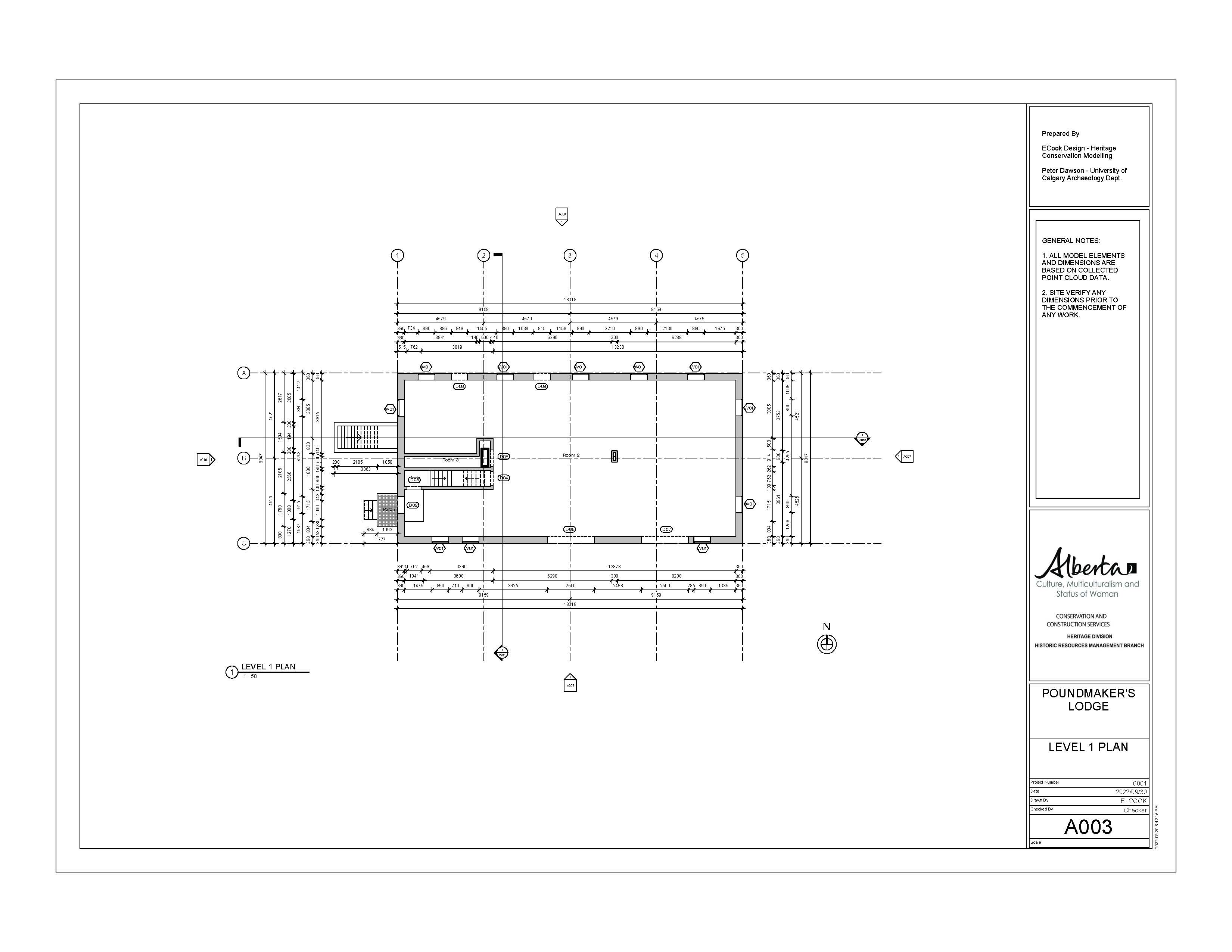

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

When it came dinnertime they hauled us to the bottom basement, that’s where the dinner quarters are. They served us “dinner,” I wouldn’t call it dinner right now. Something we didn’t like, they told you that “you gotta like it.” So what was there- because we’re so hungry even though we had a snack, we’re still hungry– we eat this stuff, I can’t remember what I ate. I know a lot of the diet here, what was here was that, Prem they call it. Prem or now they call Spam, and some potatoes and that was it.

We had our dinner, then it was almost time to bedtime. There was going to be one big meeting after breakfast at 10 o’clock or whatever. It was between the girls’ side, and the boys’ side getting all in one, under one room, still sort of segregated. Go on the same rules. Rules thing again. You know, “no talking to the girls.” Rules with, with girls, I guess. And that was kind of that how we settled what not to do. After that, it was like, I think on a Monday, we were told to “go into these classrooms.”

Even then I didn’t get to see my brother all that time. Maybe they brought him in later or different time or whatever… but it really hurts me to this day that, that four, four months passed, and I didn’t see him. Even though we were in the same dorm, not same dorm, but the same side of the building. I still didn’t see him four months, and that’s what really hurt me.

-Gary Williams

Oral interview with Gary Williams. Conducted by Peter Dawson at Poundmaker’s Lodge, St Albert, May 4, 2022. Transcribed by Erica Van Vugt and Madisen Hvidberg. University of Calgary, Jan 23, 2024.

Image: AB Archives, PR19910383412. Edmonton Indian Residential School, St. Albert, Title: [no names or description provided]. ND.

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read more

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more