Carriage House Fourth Floor

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

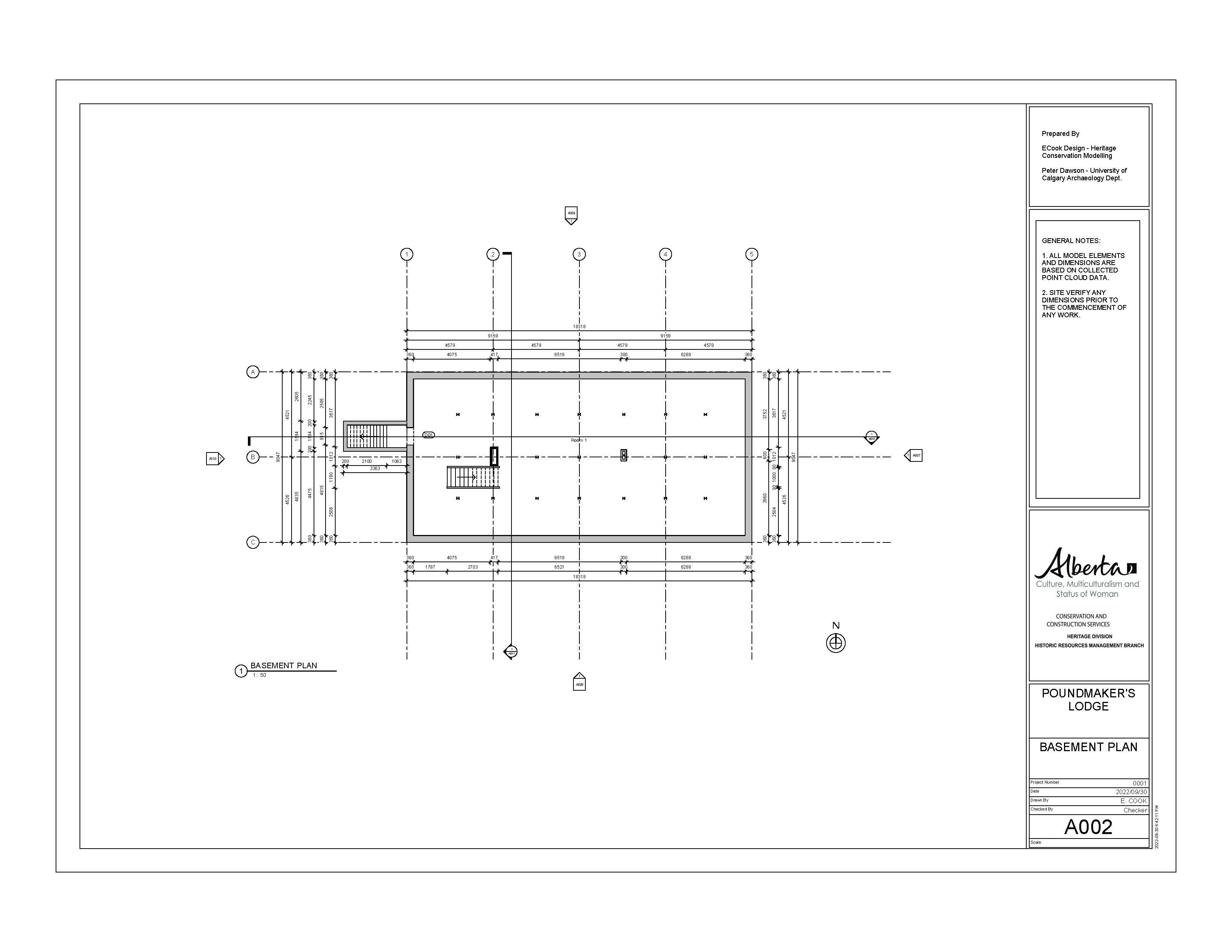

Read moreThe First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. Posts Have Been Added to Stabilize and Support the Main Floor of the Building. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud.

The basement level of the carriage house housed served as a utility room. In the main school, the basement or first floor housed similar rooms as Old Sun’s first floor and UnBQ’s first floor, including the boys’ and girls’ playrooms, the washrooms, the dining rooms, kitchen, boiler room, and utilities. Building operations based in the basement of the Edmonton IRS speak to broader trends of unsafe operations at residential schools across Canada, particularly regarding fire safety.

In October 1948, Principal Reverend E. J. Staley reported that a fire started in a laundry room cupboard from unknown causes [1,2]. The basement was significantly damaged as was the wiring and machinery, and holes were cut in the ceiling when crews were putting out the fire. While Nealy approved repairs to the school, he was firm in directing Agent Gooderham to keep costs as low as possible [1,2].

During her statement to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission at the Alberta National Event sharing panel, Isabell Muldoe of Gitxsan Nation, a Survivor of Edmonton Indian Residential School (EIRS) who was transported from her home in Haida Gwaii, recalled,

The doors were always locked. Locked going upstairs to the dorm, to the sewing room. Every door was locked. And today, well, lately, I’ve been wondering what would have happened if there was a fire? We would have been trapped. [3].

The danger recalled by Isabell Muldoe with regards to fire safety is well substantiated by fire inspection reports from EIRS. This is compounded by the lagging response to known dangers and the focus on the financial bottom line by both the government and the churches administering the schools [2]

Issues concerning water quality and quantity plagued Edmonton Indian Residential School. Hardness of well water required that it be hand pumped through soda to obtain soft water. Reports from 1928 reveal that the soda levels added were often too high to make the water both palatable and healthy. The absence of a back up water tank or cistern also made the school vulnerable to water outages. As a result, when well pumps broke (as they frequently did) students would have no access to water. In April 1937 Principal Woodsworth reported that the pipes burst in the main water pump, leaving them with no access to water for one day, and emergency repairs eight times in a twelve-month period (Edmonton Agency, Vol. 6351, Reel C-8707). Five years later, the start of the school year was delayed because of well trouble and an insufficient water supply (Edmonton Agency, Vol. 6351, Reel C-8707). In 1947, J.T. Faunt, Assistant Principal, reported that there was no drinking water on the upper floors, no basins or water taps on the dormitory floors (Edmonton Agency, Vol. 6351, Reel C-8707)

[1] Department of Indian Affairs (1919-1937). Edmonton Agency – Edmonton Industrial School – Administration [administrative records]. Headquarters central registry system: School files series (RG10, Volume 6350, Reel C-8706). Library and Archives Canada. Ottawa.

[2] Wallace, R. and N. Pietrzykowski. 2022. Digital IRS Archival Research Unpublished report prepared by Collective Heritage Consulting for P. Dawson, University of Calgary. On file in Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

[3] Isabell Muldoe. NCTR: SP205. (March 29, 2014). Alberta National Event, sharing panel (Edmonton). https://archives.nctr.ca/SP205_part06

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

This image gallery shows modern photos of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

The boys were more… they had more freedom than we did. They were able to wander around in the fields, in the bushes, and whatever, but we were fenced in like a bunch of cows. We were not allowed to go beyond the wire fences, and they were wired fences. If we were caught outside those fences we were punished, severely, strapped or else you had to do extra, extra work, along with your duty monthly duties.

We were always hungry. When we got there, our clothes were taken away, they were put in little cubicle boxes. We all had a number, and we immediately had our clothes marked by numbers. Only on Sunday could we wear our clothes that we brought along. We had to wear school clothes and by the time half of the year came along, we couldn’t fit those clothes anymore, that we brought along.

We were not told the rules when we got there. Of course, there were many rules. We learned from the others, or we learn by the mistakes that we made, while we were there, and we got punished. I don’t know if the students that were there already, who knew the rules already, might have enjoyed watching us suffer being punished because we didn’t know the rules… but, we weren’t, the rules weren’t shared.

We never went anywhere, like I said. If you were lucky enough to be in a group called CGIT which was run by United Church, the girls that were in it were lucky enough to go on an outing, and that wasn’t very often. The door doors were always locked. Locked going upstairs to the dorm, to the sewing room, every door was locked. And today, well lately I’ve been wondering… what would have happened if there was a fire? We would have been trapped. I don’t know if they ever thought of that.

The only reason we knew that a supervisor was coming was because each had a big ring of keys we’d hear them jangling, then we behave ourselves for whatever wrong we thought we were doing. We’d sit there and stand there or whatever, and act innocent- from what? I don’t know. What wrong could we do? We were locked up.

Decisions were always made for us. We never had a choice. You had to line up, you had to go to church, you had to do this, you had to do that. We had chores, and if we didn’t do them, like I said we were punished. Even today, I find it hard to make a decision.

– Isabell Muldoe

Notes:

Isabell Muldoe Testimony. SP205_part06. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Panel. March 29, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SP205_part06

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read more

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more