UnBQ Library

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read moreThe boiler room and former coal shoot at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). This large space continues to house the utilities used to heat this large masonry building. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud.

The boiler room is one of the areas of UnBQ where function and appearance have changed very little since its operation as a residential school. While there have been technological updates and modernization of the utilities, the boiler room retains much of its original appearance.

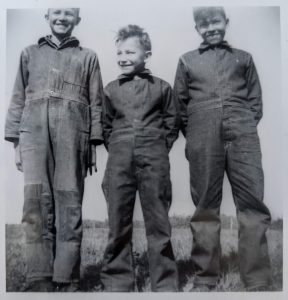

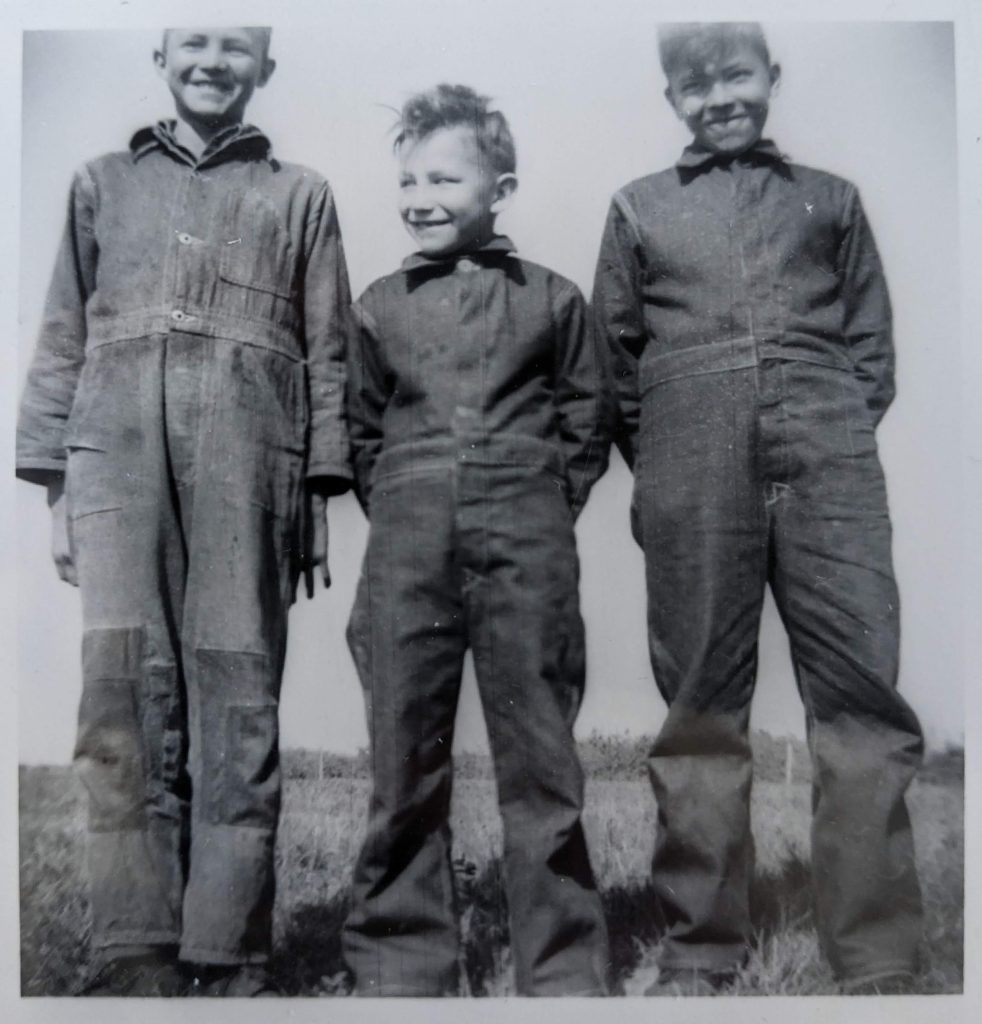

Students at the school were often responsible for tasks related to the operation of the school such as laundry, washing dishes, harvesting food from the gardens, serving staff meals, taking care of livestock, and shoveling coal. Children working at these tasks would be assigned them both as daily living chores but also occasionally as punishment.

Soon after its construction, chemical analysis of Blue Quills water supply revealed high levels saline/sodium sulfate, which is said to have a laxative effect when consumed. The extreme hardness of the water with high amounts of rust would have been harmful for both human consumption and the plumbing system itself. Despite these safety concerns, government representatives deemed the installation of a water softener to be unnecessary and too expensive.

Many of the risks faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools such as Blue Quills came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans for Blue Quills which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. In 1952, a very dangerous fire hazard was identified at Blue Quills following the construction of a new wing of the school which was accessible from two levels. Inspector F.A Ingram advised that the stairwells be enclosed so that they acted as a natural fire break to prevent the spread of fire.

The relatively remote location of Blue Quills required that fire suppression be done on site. Blue Quills had been designed to accommodate 200 students. However, a feasibility study showed that well water productivity was only able to support 100 students. This was inadequate for both fire protection and student use (hygiene and consumption). As a result, water tanks at the school were of a size that was inadequate for extinguishing any fires that might occur. Fire escapes, as seen in the virtual 3D model of UnBQ above, were also documented as being inaccessible to many students. Inspectors report that while fire escapes were accessible to students on the first floor, they were inaccessible to students on the second floor.

This image includes modern images of the boiler room. If anyone has historic photos of the boiler room at Old Sun that they would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com or submit through "Submit your Memories" button at the top of the page.

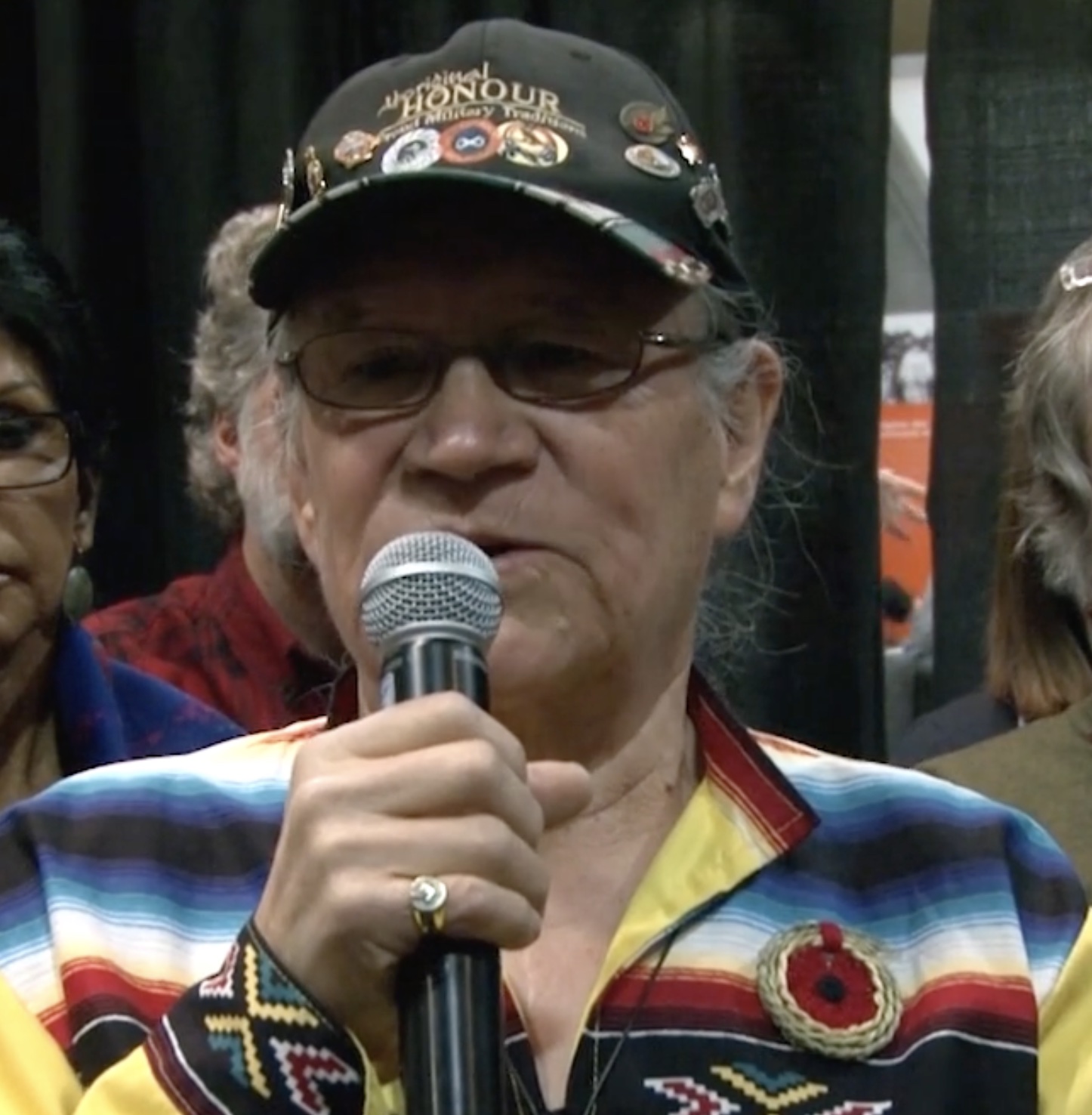

All these things that happened in residential school. You know, all the lickings and the beatings I got. Food, food was terrible. If you got sick, you get it on your plate, and then you recycle it until you kept it down. We used to walk by the priest’s dining room. You know they had a nice white tablecloth, polished silver, two candles, two bottles of wine. Great food, while we ate the garbage. Yeah, I can only say that.

I don’t remember too many happy times in residential school. I think just the Saturdays where sometimes we were allowed to go rabbit hunting, you know with sling shots. So, it’s a time to, you know, we roast rabbits out in a bush. You know, and have a good feast. Other than that, there weren’t that many happy times, you know?

I guess we had one of our boys from Cold Lake Reserve, Dene. He was good at opening doors which were locked up. So, we used to borrow the priests mass wine. We’d have two pails, two pails, one with water and one empty. They were all in big ceramic jugs with corks. We’d take a little bit and fill it up with water, shake it, and then we go to a bar or go into the nuns’ and priests’ storage room. You know, where they had all the good canned stuff, liberate some of the food and you know, that’s how we had to learn how to survive, you know?

So I can’t really remember too many happy times out there. It was all of the things that I went through. You know, the physical abuse, you know, the sexual abuse, mental abuse, spiritual abuse, cultural abuse. All those things that happened to me and it took me a long, long, long time to deal with it, you know?

– Jerry Wood

Notes:

Jerry Wood Testimony. SC143_part02. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Circle. March 29, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SC143_part02

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more