UnBQ Boiler Room

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

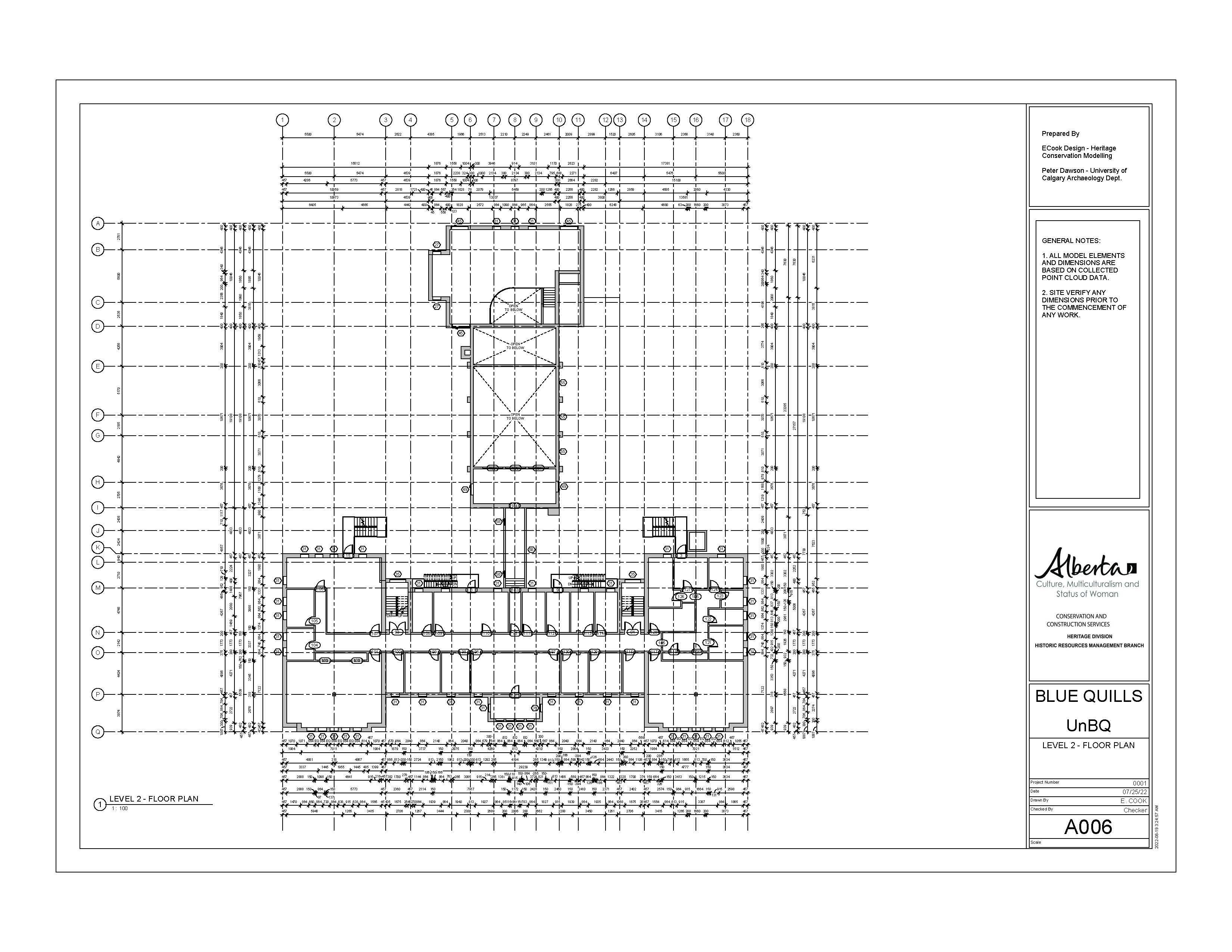

Read moreThe 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ). Important rooms on this floor include the junior boys and girls dormitories and the boys and girls Infirmary. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions.

Today the second floor/third story of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ) houses a combination of offices, classrooms, and a staff kitchen. At the center of this floor, access to a mezzanine above the library can be gained. This space is used as a meditation room, but originally functioned as the choir house for the chapel.

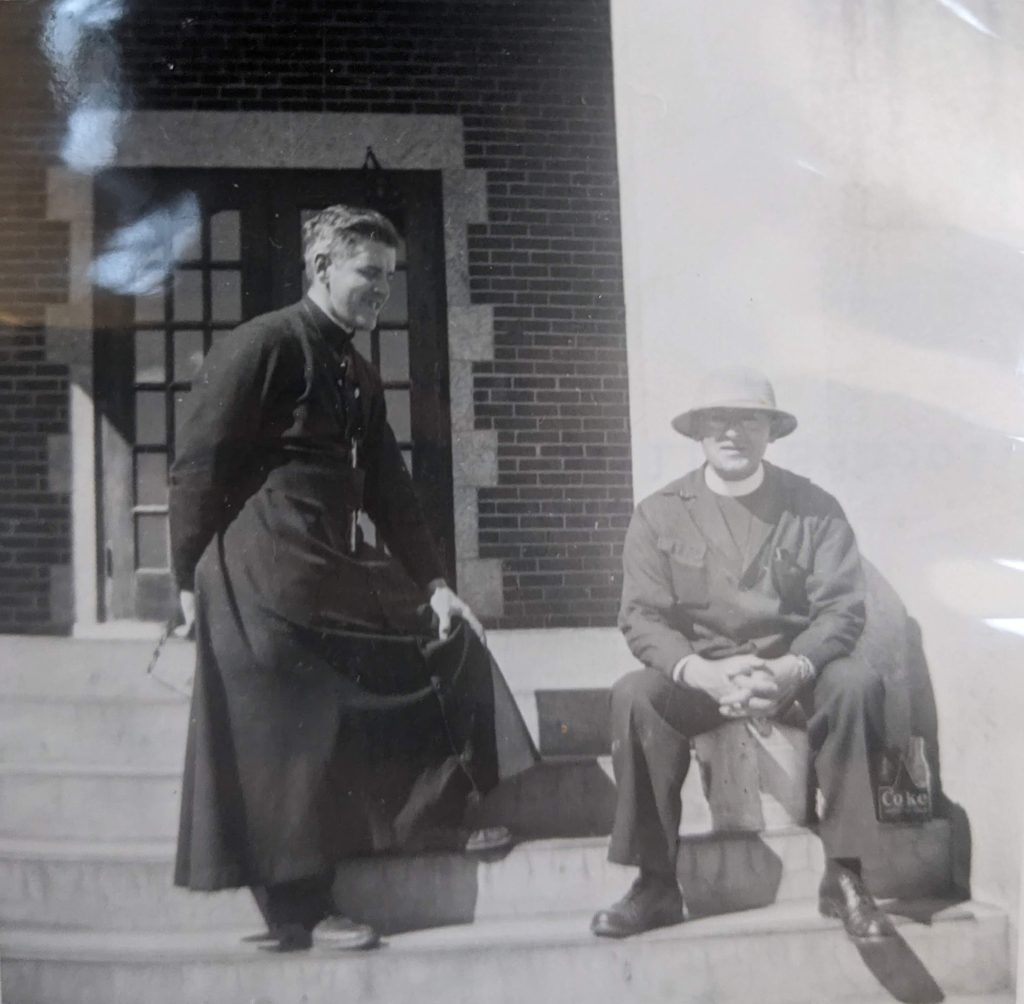

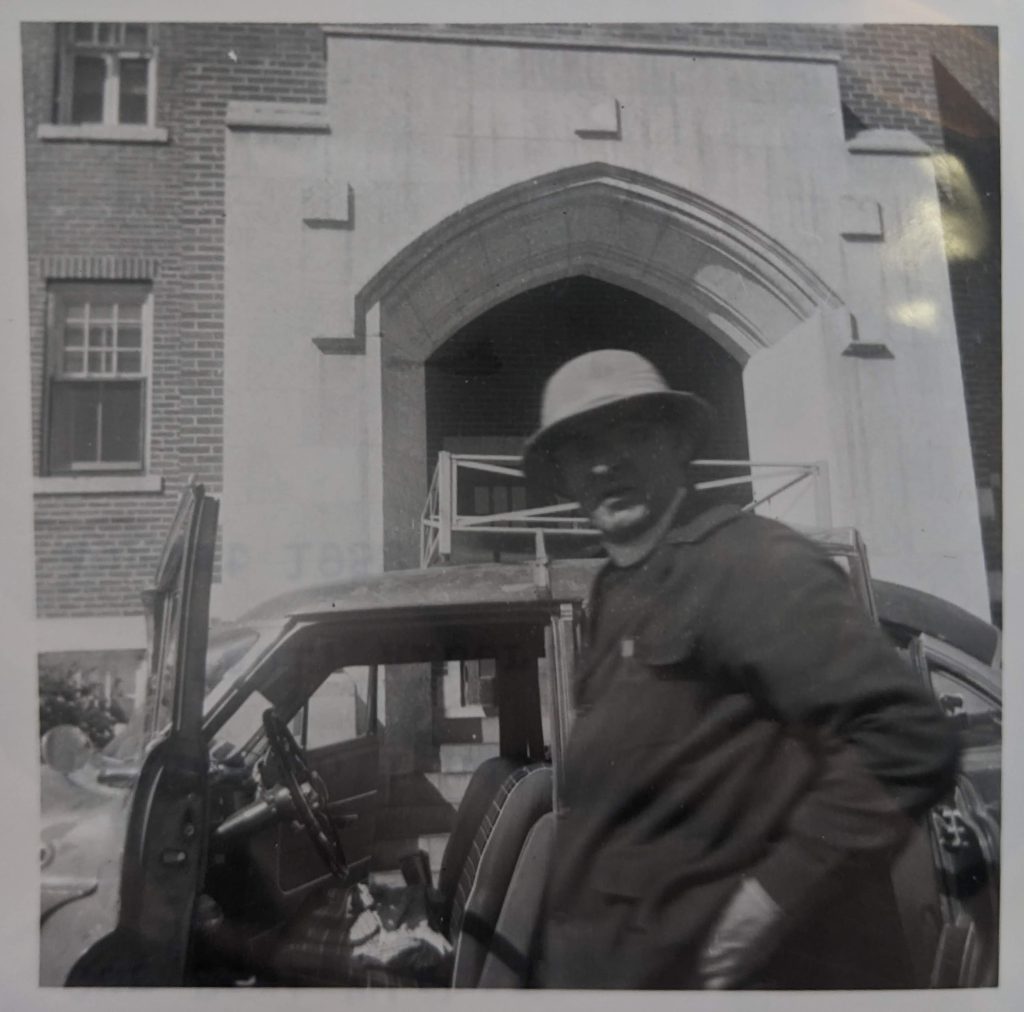

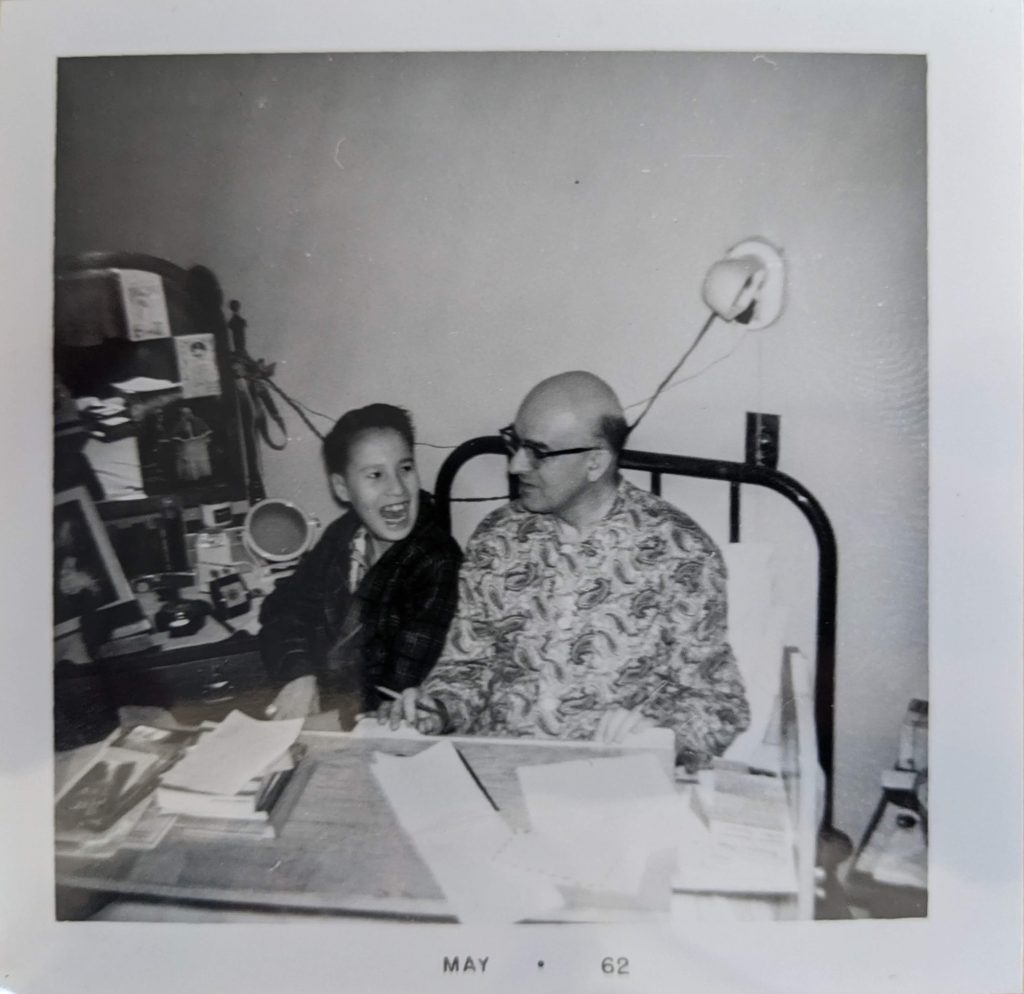

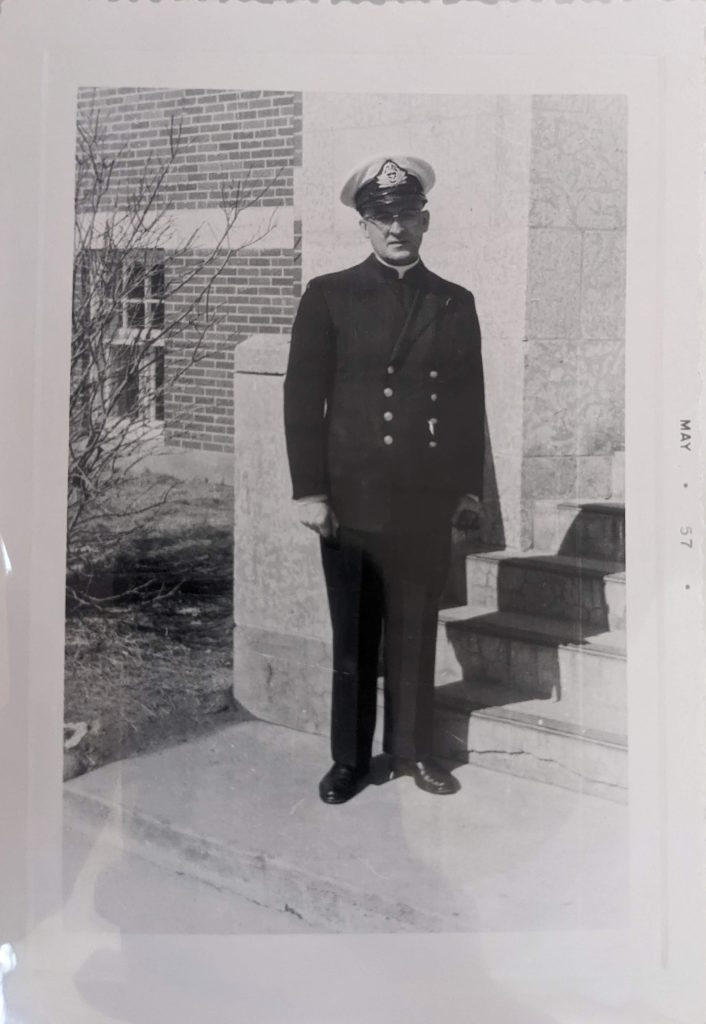

When in operation as a residential school, this floor housed some teaching spaces, such as classrooms and a sewing room. The mid section of the floor was used primarily as staff quarters for supervisors, teachers, and maintenance workers who lived on-site at the school. The principle, who was often also the priest would also live on the premises, although in his own separate house alongside his family. The groundskeeper likewise had a house separate from the main school building.

Relationships between staff and students were often difficult. The students’ dormitories were on the floor above the staff, with supervisors intentionally situated between students and building exits. Students were strapped with thick leather belts from farm machinery for not following rules such as being quiet or as Verna Daly remembers, for speaking Cree or Dene, the home languages of many of the students at Blue Quills. Marcel Muskego recalls being strapped in the hallway so other students could hear his screams, and does not recall what the punishment was given for.

Generally, staff created a better living experience for themselves in the school than they did for the children they were responsible for. For example, supervisors ate in a separate room off the dining hall with ornate table settings and “great food while we ate garbage,” remembers former student Jerry Wood.

Not surprisingly, overcrowding led to an increase in the spread of communicable diseases in all three schools. Most concerning was the spread of TB. At OS tuberculosis was on the rise in 1935 with five students in the hospital and the remaining student population put under observation with a rest period every afternoon (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6360, Reel C-8714, 1935). Two years later, the Indian Agent reported that nurses with TB experience attended the school because of the high need, but that this service must be funded by the band. The Agent questioned if this on-going medical funding to treat TB should be a departmental obligation (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6360, Reel C-8714, 1937). Correspondence from the Saddle Lake Agency in 1941, noted that a polio outbreak had occurred at both BQ and EIRS, and that the students returned to school on September 23 after the ban was lifted. There was no other mention or details provided about the duration or severity of the outbreak (Saddle Lake Agency, Volume 6346, Reel C-8703, 1941).

The DIA sought solutions to reduce disease transmission by looking at the bathing practices rather than addressing the problems with overcrowding. At BQ showers replaced washbasins in an attempt to limit the spread of communicable health conditions like scabies and impetigo. Ironically, the washbasins were repurposed at another school as a cost cutting measure – despite the believe that they were the source of disease transmission.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel to different areas of the third floor by clicking on the floating arrows.

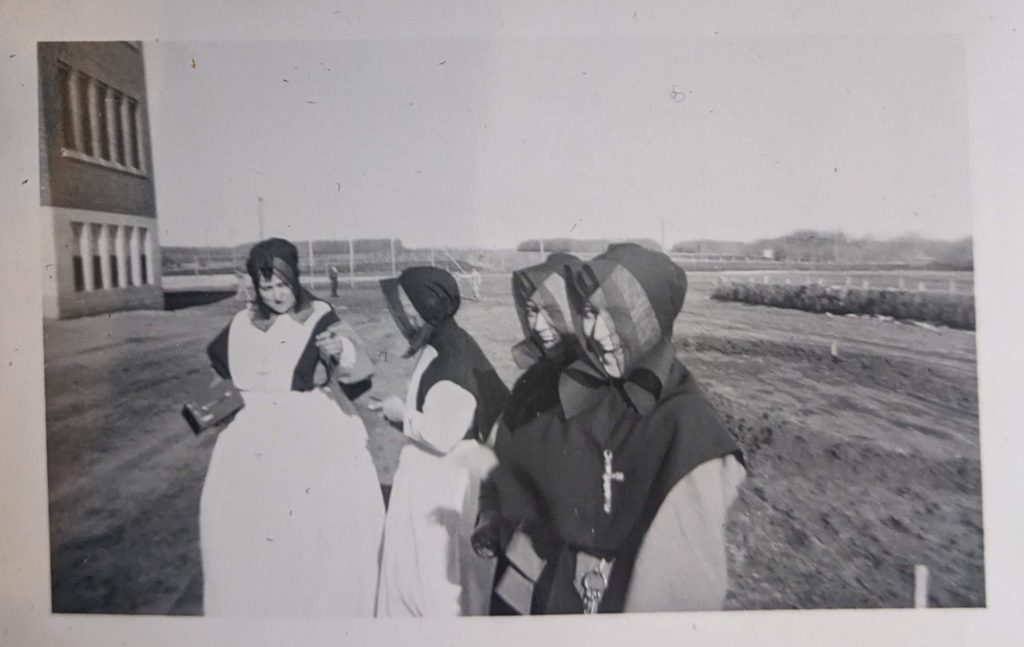

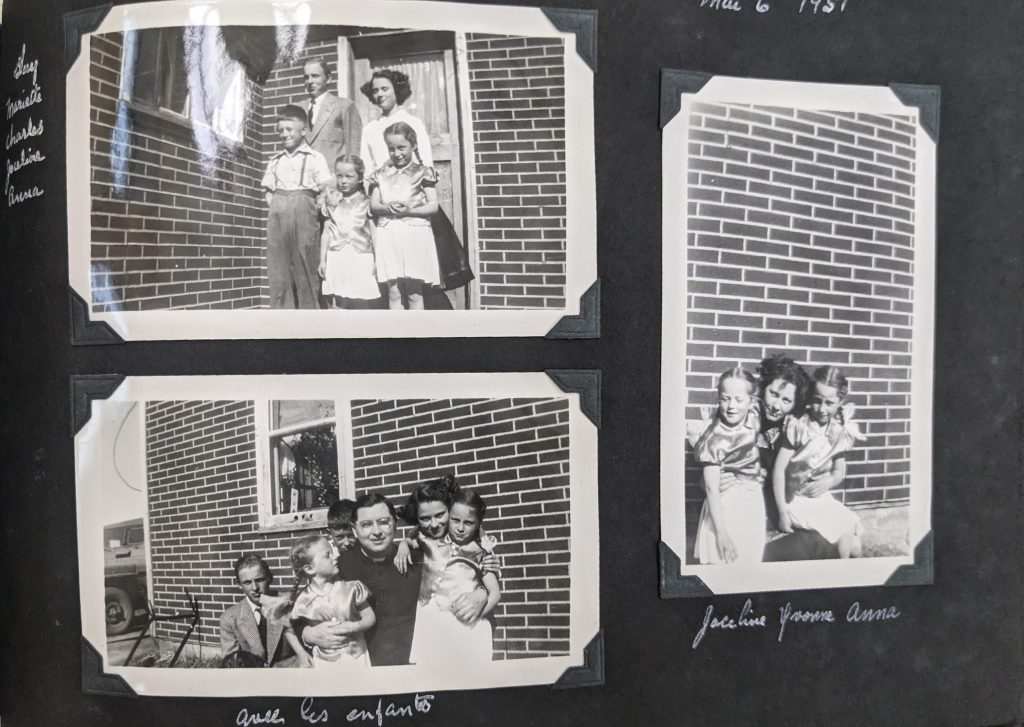

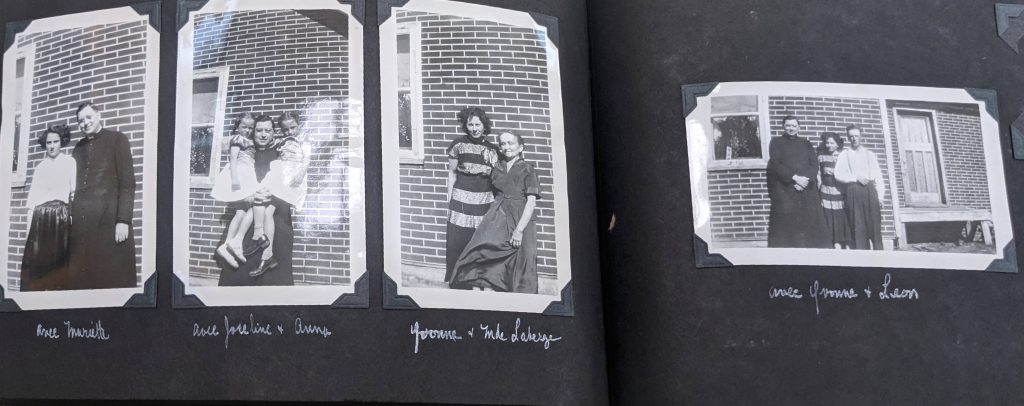

This image gallery includes modern and archival photos of UnBQ's third floor.

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to Old Sun Community College. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by the Old Sun Advisory Committee.

Some of the threats faced by Indigenous students attending residential schools came from the buildings themselves. The architectural plans contained in this archive, which have been constructed using the laser scanning data, illustrate how poorly these schools were designed from a safety perspective. There were three specific areas that placed the health and safety of students at great risk: Fire Hazards and Protection Measures; Water Quality, and Sanitation and Hygiene. As you explore the archive, you will find more information about the nature of these hazards and their impact on students.

We grew up, I remember my childhood, it was always loving and caring fun. The siblings played together in winter, summer, didn’t matter, fall. We all were together, until that fateful day we were brought to residential school.

I was seven years old and I left at eleven years old. First day of school was a culture shock to me. I remember we were all brought into the shower room. Everybody had to take a shower and we got out of that room, and I fainted. I just dropped. I don’t remember very much of that first year at school because I was so homesick, I was sick most of that year, and I seen the horrific things that happened to other children there.

I learned to be standing alone at an early age. I’d seen other children’s, their ears bleeding because somebody was pulling on their ears. I’d seen our young men being ridiculed, and laughed at by the people, the masters and the nuns that were looking after them. I saw that and it hurt me, pretty badly.

I must have been about eight years old, nine years old. I saw my sister, she was only six years old. When she went to residential school, she started wetting her bed and they brought these little children into the refectory for breakfast with their wet sheets on their heads. And I hated those people that were looking after them, I could feel the hair on my back standing. Seeing that my little sister with her sad eyes and tears in her eyes, and we couldn’t go up there and comfort her.

I was so thankful that I didn’t have to go back, I was there until grade four. Now we couldn’t talk to our brothers. My brother was on the other side, on the boys’ side. There was very seldom that we ever talked to him, but there was one thing that was happening at that school, at Blue Quills, was the boys had a band, and my brother was in the band, in the cadets. And to this day, I was so proud of him, and the other boys that we’re in there.

– Agnes Gendron

Notes:

Agnes Gendron Testimony. SP203_part08. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Panel. March 28, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SP203_part08

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read more

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâk…

Read more