University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills

The University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (UnBQ) operates out of the Blue Quills IRS building constructed in 1930. Now UnBQ is governed by Beaver Lake Cree Nation, Cold Lake First Nations, Frog Lake Cree Nation, Heart Lake First Nation, Kehewin Cree Nation, Whitefish Lake First Nation #128, and Saddle Lake Cree Nation.

“A school for Indian girls would be of great importance, and I may say, would be absolutely necessary to effect the civilization of the next generation of Indians. If the women were educated it would almost be a guarantee that their children would be educated also and brought up Christians, with no danger of their following the awful existence that many of them ignorantly live now. It will be nearly futile to educate the boys and leave the girls uneducated.”

– Father Hugonnard of Lebret, 1885

Sacred Heart School, the Origins of Blue Quills

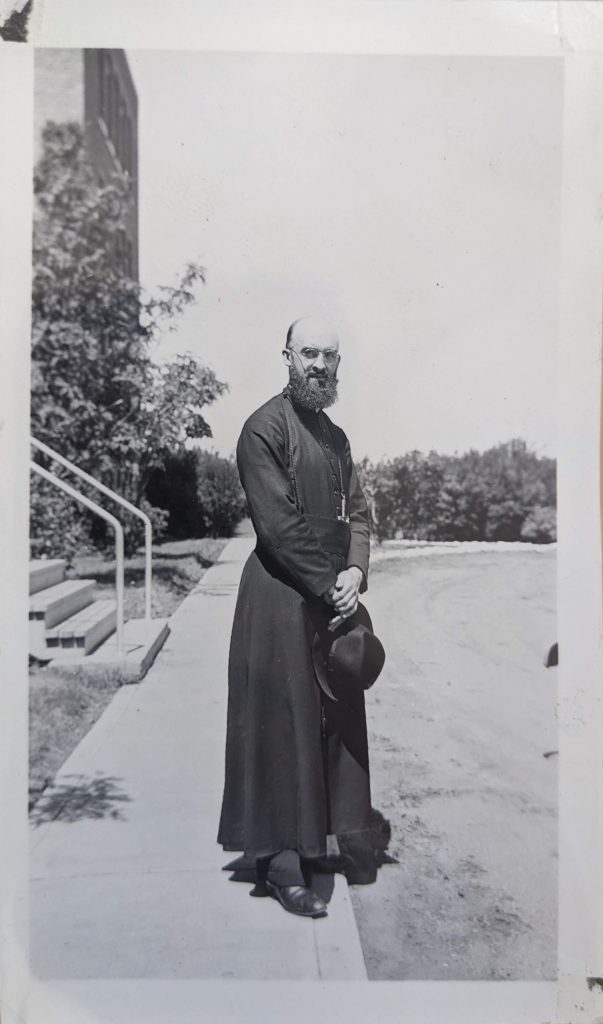

The history of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills dates back to 1857, when La Mission Notre Dame des Victories Mission School was opened by the Order of Mary Immaculate, part of the Catholic Church, in Lac La Biche. In 1889, the school was moved onto the Saddle Lake Cree Nation reserve but was initially contested, as the Sacred Heart School run by the Protestants was already operating on Saddle Lake [1]. However, Blue Quill’s Band accepted the school and allowed the construction of the Catholic school to commence, which was renamed Blue Quills [2]. Blue Quills Indian Residential School was run by the Grey Nuns and Oblate Priests and by 1893, was running an industrial program for twenty children [1,2].

While on the Saddle Lake reserve, Blue Quills had a reputation among parents for low quality education, however government inspectors between 1914 and 1920 reported satisfactory conditions in the school [1]. The nursing reports from the reserve school reported issues such as ‘mouth breathers’, stooped posture, lazy walking, and poor physique which was attributed to their race but was likely due to student’s poor nutrition and health conditions [1]. It is apparent from reports that student abuse, such as maltreatment and likely physical assaults, was occurring at the school. There are reports of a thirteen-year-old student being pregnant sometime during the reserve school’s operation, which was attributed to an Indigenous man but little actual investigation occurred [1].. This event was used to support the policy of keeping pupils at the school full time and during vacations until they are sixteen years old, a policy that was put in place at the Indian Residential School that eventually replaced the reserve school [1]. In 1928, the Department of the Interior acquired a township section (Section 11, Township 58, range 10, west of the 4th meridian) for the purposes of building a new boarding school, Blue Quills Indian Residential School; a decision made after a fire destroyed the stable at the reserve school [1].

The New Blue Quills School

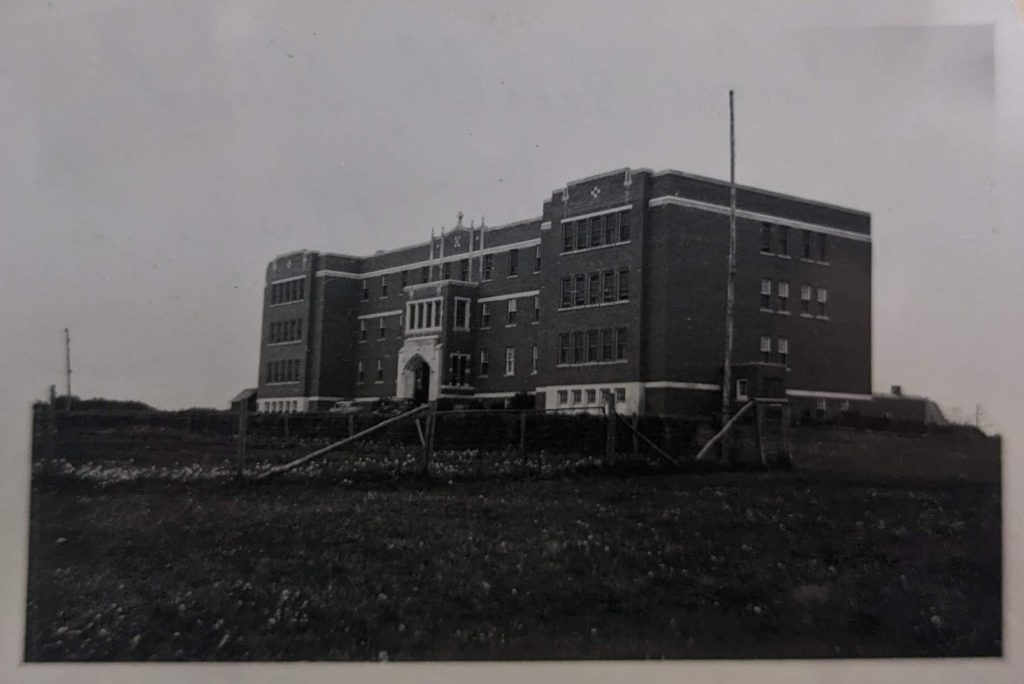

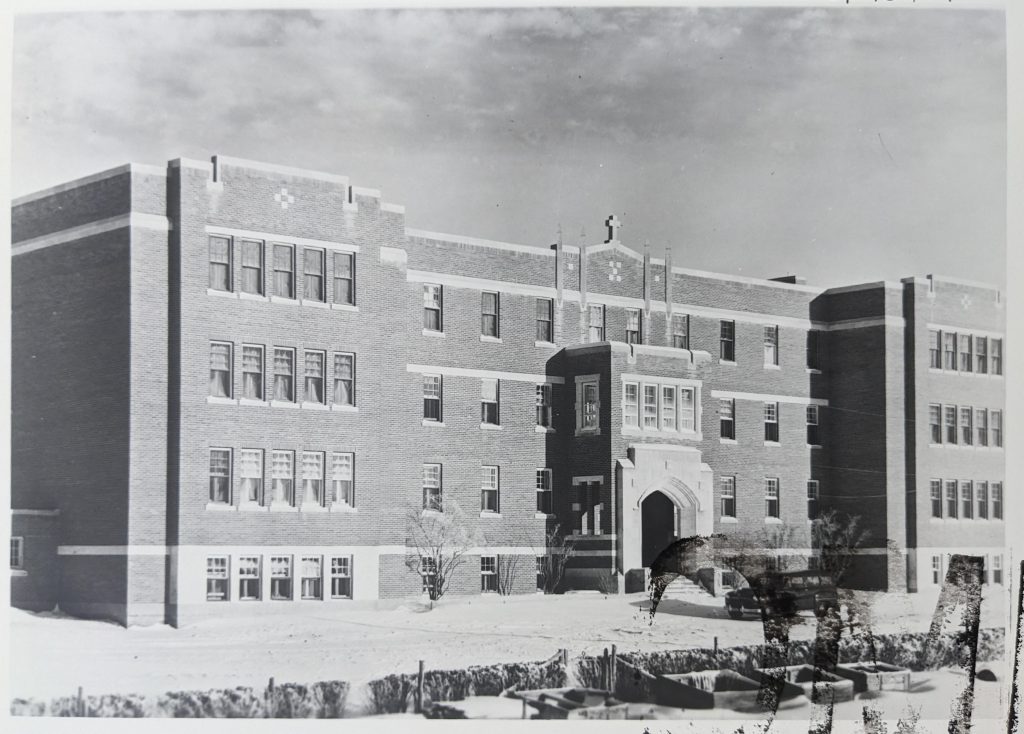

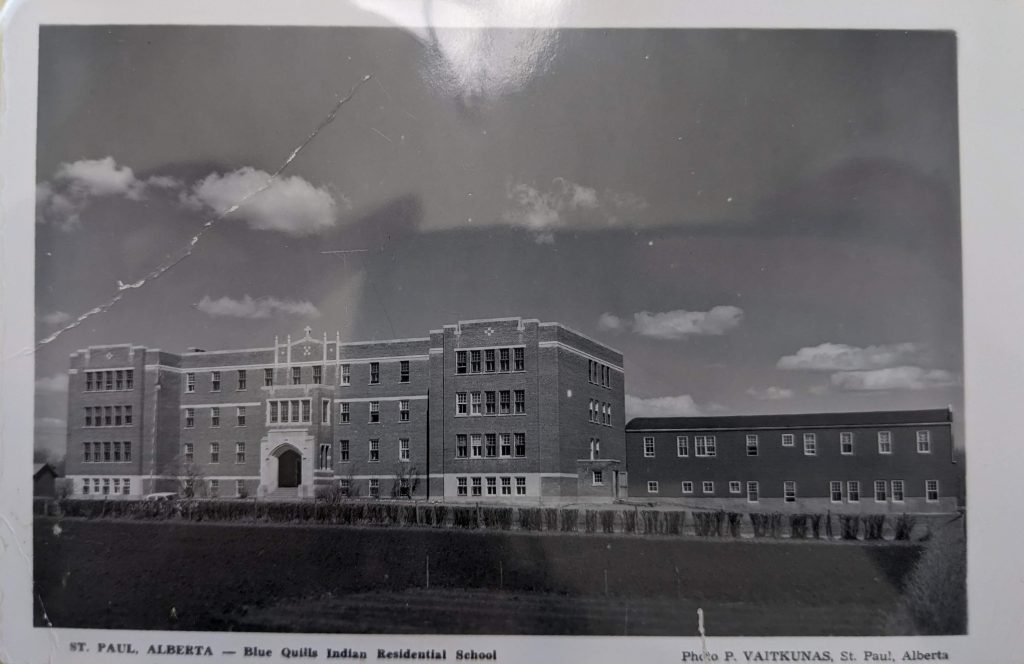

University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills operates out of the Blue Quills Indian residential school brick building constructed on the Blue Quills First Nation Indian Reserve in 1931. The Residential School served students from Saddle Lake Indian Reserve #125 (Saddle Lake Cree Nation), Puskiakiwenin Indian Reserve #122 and Unipauheos Indian Reserve #121 (Frog Lake Cree Nation), Beaver Lake Indian Reserve #131 (Beaver Lake Cree Nation), Whitefish Lake Indian Reserve #128 (Saddle Lake Cree Nation and Whitefish (Goodfish) Lake First Nation #128), Cold Lake Indian Reserves #149, #149a, and #149b (Cold Lake First Nations), and likely students from other communities in the vicinity [1]. The new Blue Quills Indian Residential School was built following the standardized structure common to most residential schools constructed at this time. In the spring and summer of 1931, 84 students were moved to the new school [1].

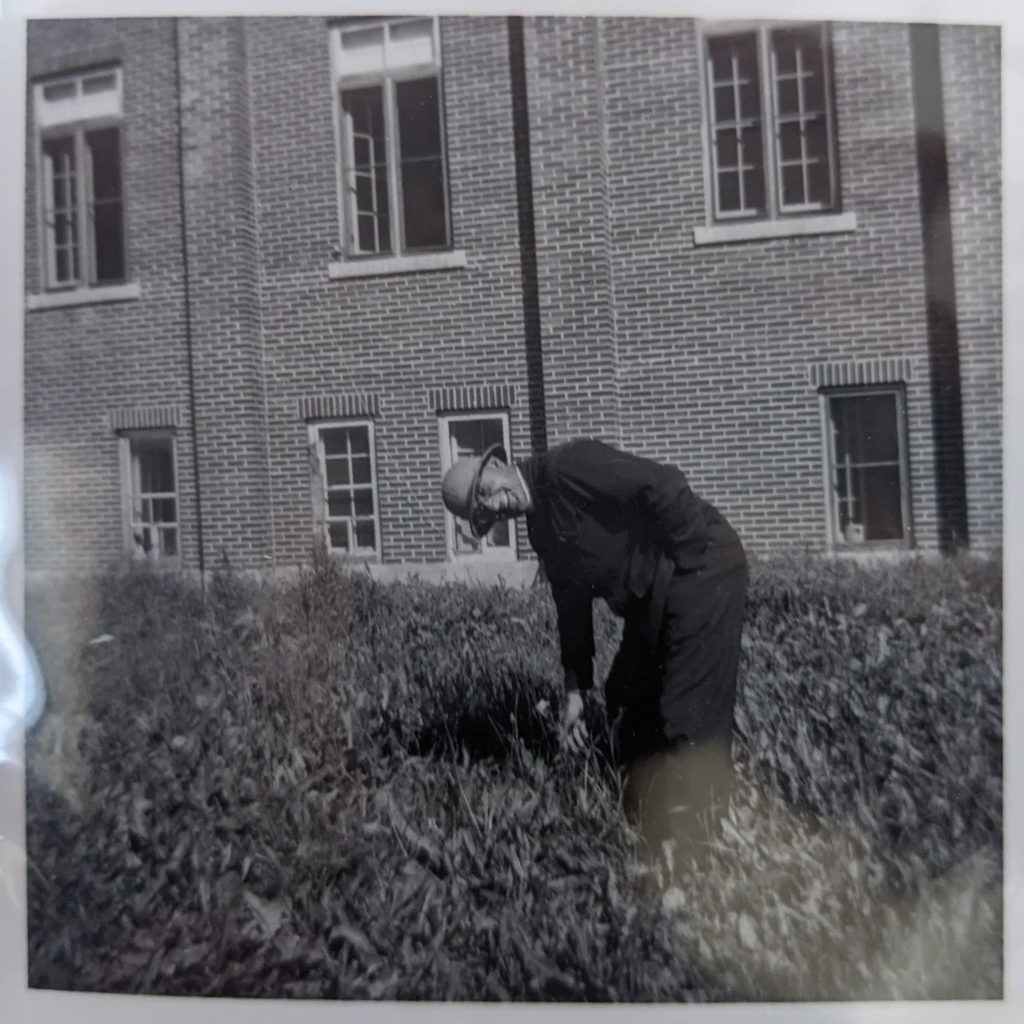

The schedule of the Residential School was different than the reserve school, as the boarding school shifted to have an even greater focus on an industrial complex, with half the day focused on industrial skills including farming and housework, and the other half of the day focusing on education. For boys, this meant working on the farming operations that were at the school. In 1934, the school reportedly had 130 acres in wheat, oats, and green feed, 4 acres of potatoes, and 1 ½ acres of garden [1]. Boys would work on the farm during the mornings, which may include milking cows, butchering pork or beef, then returning to class in the afternoon. Female students alternated their industrial work in the kitchen, the sewing room, or laundry room [1]. The food children had to produce and eat at the school was not subject to standard health testing. In particular, the milking cows were not tested for tuberculosis under broader Canadian safety standards. Tested milk would be brought in for the staff, while students had to drink what was produced from diseased cows on the farm. These procedures are still undergoing review, but the Acimowin Opaspiw Society (AOS) says records from the Catholic church provided information on how many children died from tuberculosis during the operations of Blue Quills, which is now estimated to be nearly 400 [2].

The conditions faced by the students followed the complete Institution model found in other Residential Schools – boys were forced to shower in groups of 12, students were compelled to only speak English, corporeal style punishment was common, and they followed intense religious practices. The health conditions of the school were also poor, with several accounts of Blue Quills Indian Residential School being quarantined due to the spread of diseases, including tuberculosis [1].

Throughout Blue Quills active period as a government-run Indian Residential School, there was resistance among students. In 1929 and 1932, attempts were made to burn down the schools which were unsuccessful, although arson of the barn was successful [1]. The most common form of resistance was students attempting to run away. Particularly after the move of the Residential School, there was an uptick in the number of students who escaped and attempted to return home [1]. The federal government decided to close the residential school in 1970, when Saddle Lake First Nation members peacefully occupied the school in protest. On January 1, 1971 the occupation concluded in the takeover of the facilities by the Blue Quills Native Education Council making Blue Quills Canada’s first residence and school controlled by First Nations.

The school was open between 1890 and 1970, first in Lac La Biche, then on Saddle Lake Cree Nation before moving to its location just to the West of St. Paul. The current brick building for this school was constructed in 1931, when Blue Quills Indian Residential School was opened as a Catholic school for children in the Saddle Lake area, located on Treaty 6 Territory.

Reclaiming the Blue Quills Residential School

In 1969, former Blue Quills student Stanley Redcrow was one of only four Indigenous staff members at the school – none of whom were teachers. Redcrow and others began advocating for the hiring of Indigenous teachers at Blue Quills but were repeatedly told none were qualified. Things came to a head when it was learned that the Department of Indian Affairs intended to sell the Blue Quills school building to the town of St. Paul, Alberta for the sum of one dollar.

Redcrow and others mobilized and organized a group called the Blue Quills Education Council which was mandated to bring the education of Indigenous children back under the control of their communities. A sit-in was initiated in July 1970 to make sure their intentions were taken seriously by Indian Affairs. Over a period of 17 days, the protest involved as many as 300 people and received national and international attention.

An invitation was extended to then Minister Jean Chrétien to visit Blue Quills and meet with the protestors. After some negotiation, 20 protestors were flown to Ottawa where an agreement was eventually signed which effectively transferred operation of Blue Quills over to the Native Education Council. Funding to develop educational programming was also provided by the Federal Government.

The reopening of Blue Quills in 1971 as an Indigenous-led school dramatically transformed the institution. Courses in Cree language and Indigenous arts were now offered along side those in math and science.

Today UnBQ is governed by Beaver Lake Cree Nation, Cold Lake First Nation, Frog Lake Cree Nation, Whitefish Lake First Nation, Heart Lake First Nation, Kehewin Cree Nation, and Saddle Lake Cree Nation, plus one Elder from the Saddle Lake First Nation.

Notes:

[1] Persson, Diane Iona. 1980 Blue Quills: A Case Study of Indian Residential Schooling. University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

[2] Blue Quills First Nation College. 2001 30th Anniversary Commemorative Book. Blue Quills First Nation College.

[3] Mertz, E. “Children died from drinking unpasteurized raw milk at Saddle Lake residential school: advocacy group.” Global news, electronic document https://globalnews.ca/news/9432774/saddle-lake-cree-nation-residential-school-investigation-report/, accessed October 26, 2023.

Left click and drag your mouse around the screen to view different areas of each room. If you have a touch screen, simply drag your finger across the screen. Your keyboard's arrow keys can also be used. Travel to different areas of the school by clicking on the floating arrows.

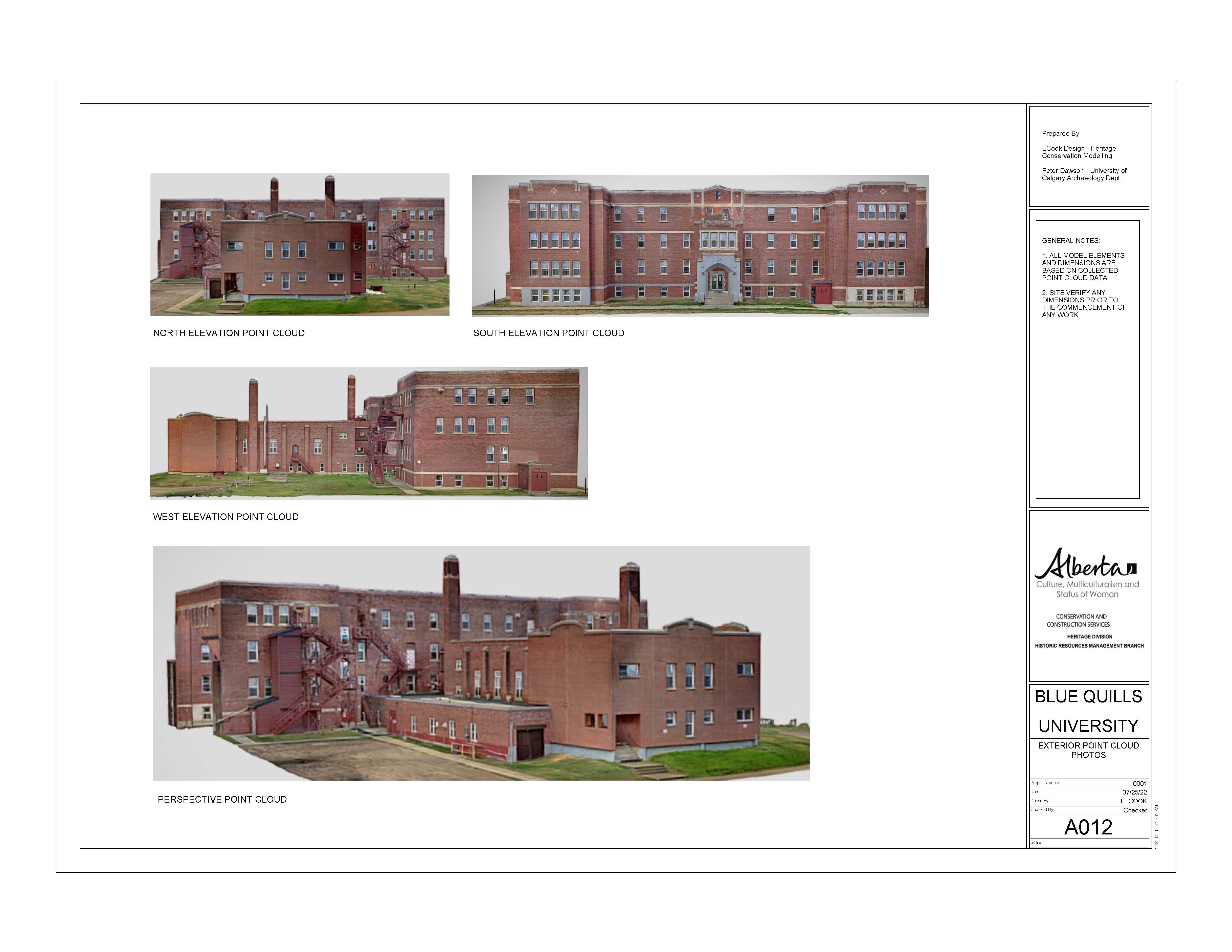

This gallery contains both modern and historic images of the University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills and Blue Quills Indian Residential School building.

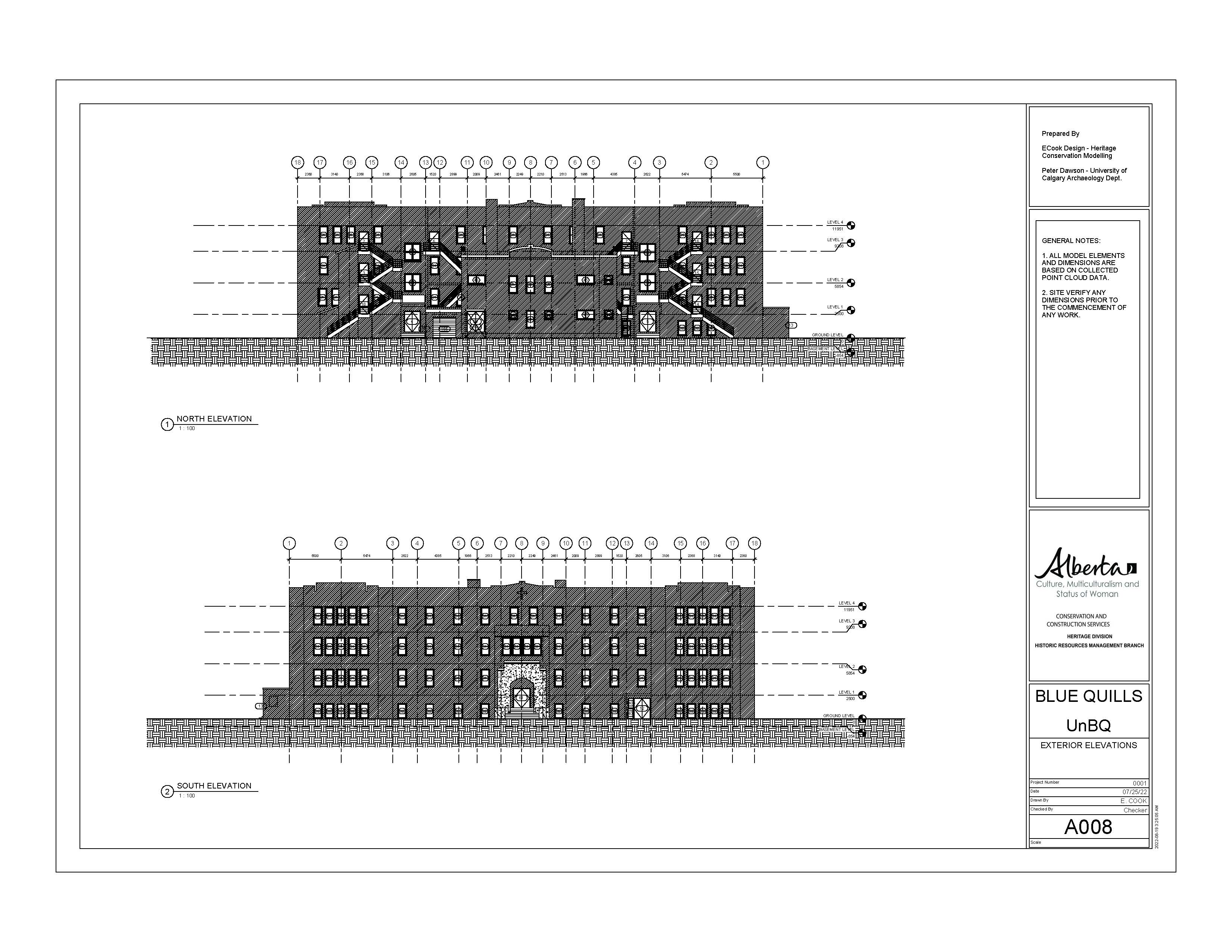

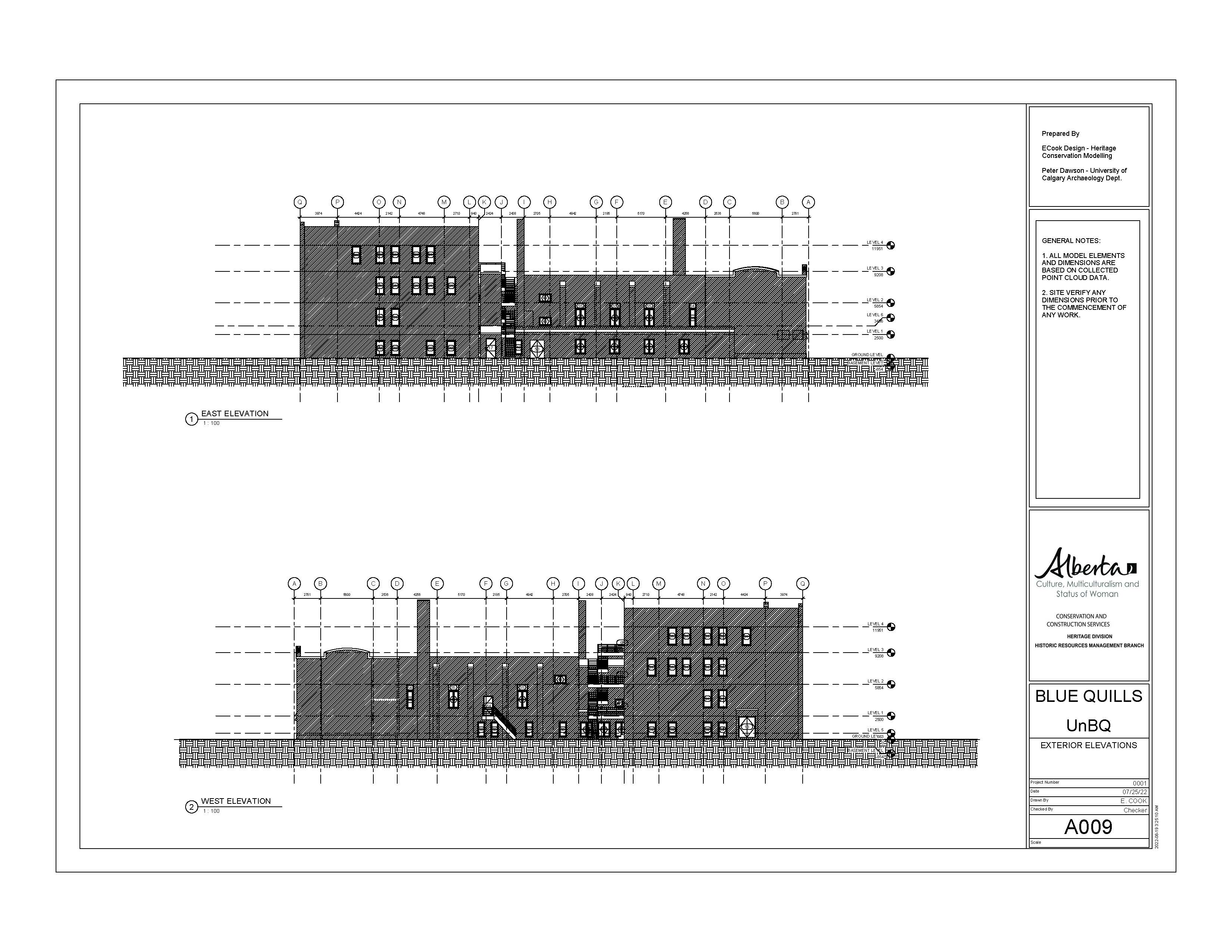

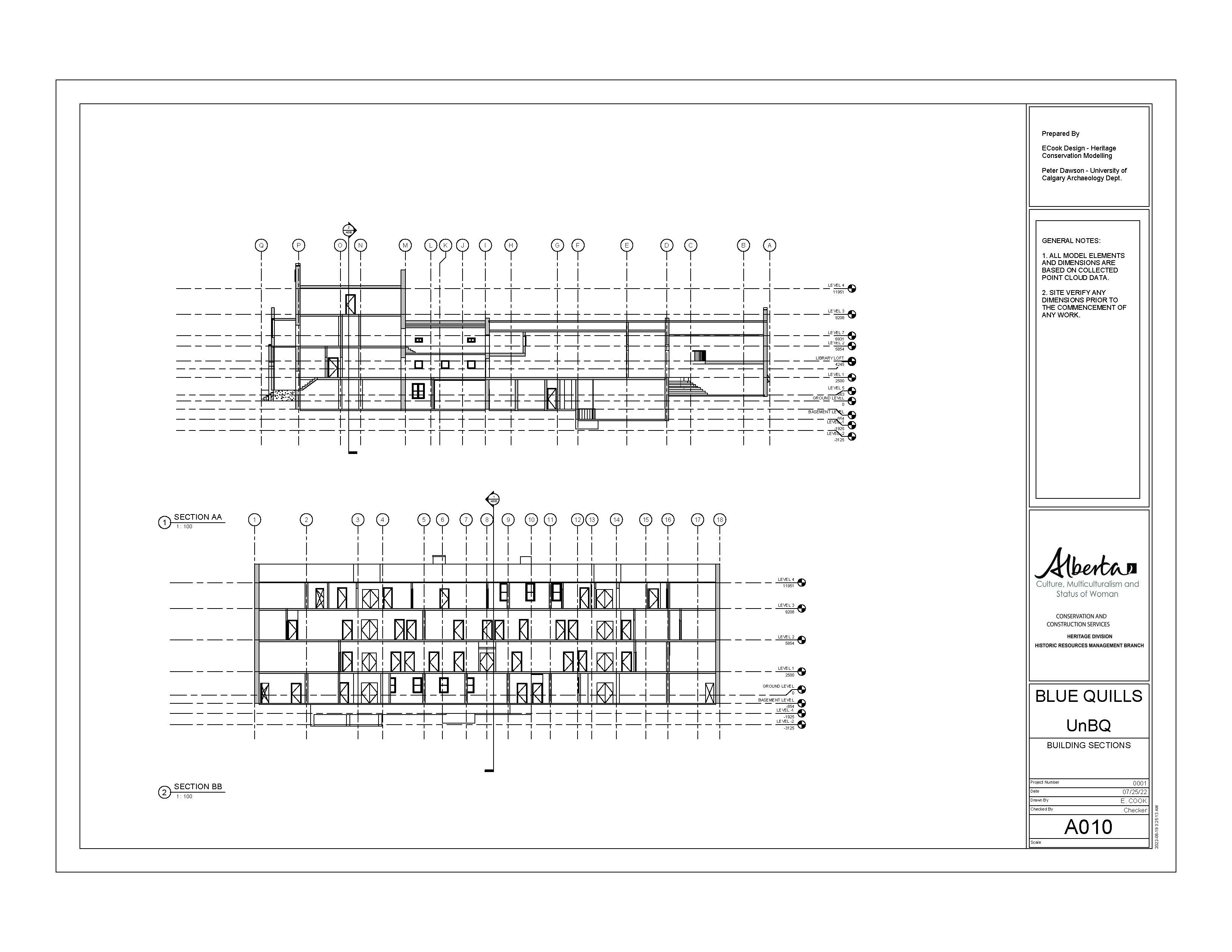

A “One Size Fit’s All” Approach

If you look at the building plans and 3D scans of Old Sun and Blue Quills, you will be struck by how similar each appears. This is symbolic of the “one size fits all” approach taken by the church and government for assimilating Indigenous children into mainstream religious and Euro-Canadian lifeways. This is seen when planning for the new Old Sun IRS building after its fire in 1928 when the blueprints for the IRS in Lytton, BC was used as the model for OS, near Cluny, Alberta (Blackfoot Agency, Vol. 6359, Reel C-8714, 1929). Where Lytton has relatively short and mild winters, Siksika has long and dry winters. Despite their dramatically different winter weather – which occurs during the school year – the same heating system was installed in both schools.

This practice is also evident when a “surplus” water softener from Blue Quills IRS was repurposed and sent to St. Paul’s IRS, many kilometres south (Saddle Lake Agency Vol. 6346, Reel C-8703, 1939). There is no correspondence in these records that indicates that the water was tested and compared, but rather suggests this one-size-fits all was applied to building practices across the wide and diverse landscape of Western Canada.

Eric Large- Indigenous People are Still Being Controlled

So they couldn’t tell lies as such, because your honor, your name was at stake, and your… survival of yourself, and your family, and your clan or tribe- so they had to be truthful. So, I guess I can only rely on that and whatever I say is not meant to hurt anyone, past, living or to exist in the future.

However, the control I guess, in the sense that we are Indigenous people are still being controlled by the government, policy, legislation, court decisions. They’re members of churches, congregation. Beliefs are a form of that continuing control, indoctrination and other processes that are involved that had their origins in the Indian policy of assimilation and integration. These were actual policies.

And these are the ones that are recorded in documents, in archives, libraries, and will eventually be reformulated into books, articles, more research to be done.

So I guess to end on a positive note, I do favor education, public education, such as this forum here. It’s unfortunate there’s not more people here, Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people, because that’s the work that’s being called for, public education and information on the Indian residential school experience.

– Eric Large

Notes:

Eric Large Testimony. SP116_part20. Shared at Red Deer Hearing Sharing Panel. June 6, 2013. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SP116_part20

Explore Floors and Rooms

UnBQ Boiler Room

The boiler room and former coal shoot at Universit…

Read more

UnBQ Library

The Library at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į n…

Read more

UnBQ Third Floor/Dormitories

The 3rd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

UnBQ Second Floor

The 2nd Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

UnBQ First Floor

The 1st Floor of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more

UnBQ Basement

The basement of University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į…

Read more