Carriage House Third Floor

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read moreThe Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. This Space Originally Served as a Dormitory and Infirmary for the Edmonton Indian Residential School. It is Notable for the Large Amount of Children’s Graffiti Found on Various Walls. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room function

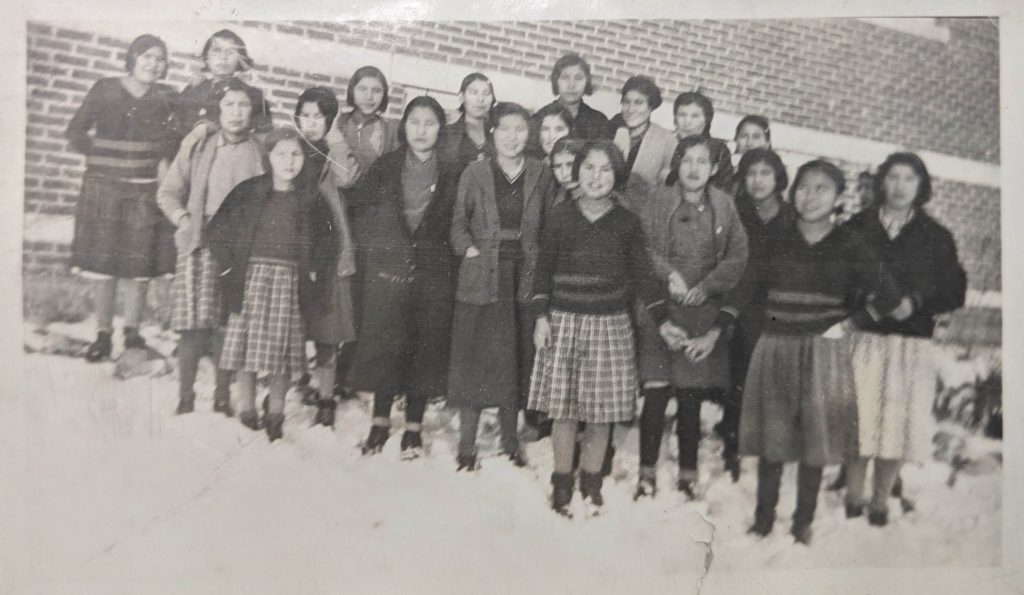

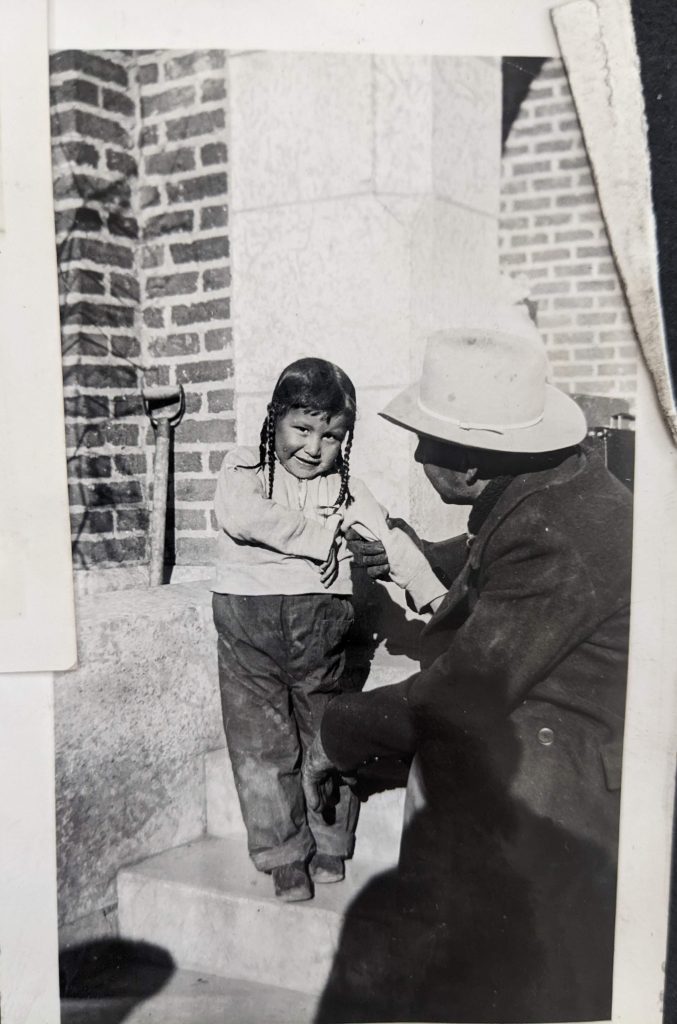

The third floor of the carriage house, which is an uninsulated attic, was used as extra room space for students. At different times, it was used as an infirmary to house sick students or as a dormitory for students who were about to leave the school. Emptied of the beds with their thin mattresses, this unfinished attic is left covered with pencilled on graffiti from former students. Some of these pieces date as far back as the 1930s, and many are from times during the Christmas holidays. Children were not only spending the break at the school, but winters in this room.

Students were intentionally kept apart from their families. A sense of alienation and isolation was built into the landscape of the schools which were constructed in remote locations, off-reserve, and frequently along unfinished roads. The school administration conveyed their frustration with being so alienated from towns and villages in various correspondence over the years. For example, more than two decades after it was constructed, Principal Woodsworth complained that EIRS remained nearly inaccessible as the road conditions made it “practically impossible” to move between school and the city after a decade of heated correspondence on the issue.

Due to respect out of family and community members of the former students who wrote their name here, we have omitted photos of graffiti from the public archive. These have, however, been photographed and preserved with this project. Community members interested may contact the Poundmaker’s IRS Advisory group via email.

Sanitation issues occurred at EIRS soon after opening. Water pressure was too low to allow toilets to properly flush. For a period of two weeks in 1924, students and staff had to carry pails of water into the bathroom in order to flush the toilets properly. Water pressure issues also prevented the use of laundry facilities during this period. A recommendation made to change the water tank system to address the issue was rejected by government officials because of the associated financial costs.

During an inspection seven years later, the boys’ washrooms were deemed unfit for use because of serious sewage backups caused by gravel in the septic tank which had clogged the syphon used to empty the tank. These problems stem from the fact that the septic system was poorly designed, resulting in sewage passing too quickly through the tanks and emptying into a pond roughly 100 yards from a barn, and 300 yards from the school. This resulted in frequent drain back ups – sometimes as many as four times in 15 months. Inspection reports indicate that septic system failure was a constant problem for 25 years at EIRS – yet at no time were long term repairs ever undertaken.

Residential school Survivors often speak of chronic medical conditions caused by attending residential school, the most common of which is respiratory illness or damage. All three schools had issues with dust particles from the unsealed cement floors and long histories of water seeping through walls, roofs and ceilings – often for months or longer – without being addressed. In the case of BQ IRS the school opened to students shortly after being built near St. Paul without having sealed its flooring. At his first inspection of the BQ IRS in August 1932, Inspector of Indian Agencies M. Christianson focused a great deal on the floors noting that dust rose continually off the floors, leaving dust particles in the air throughout the building.

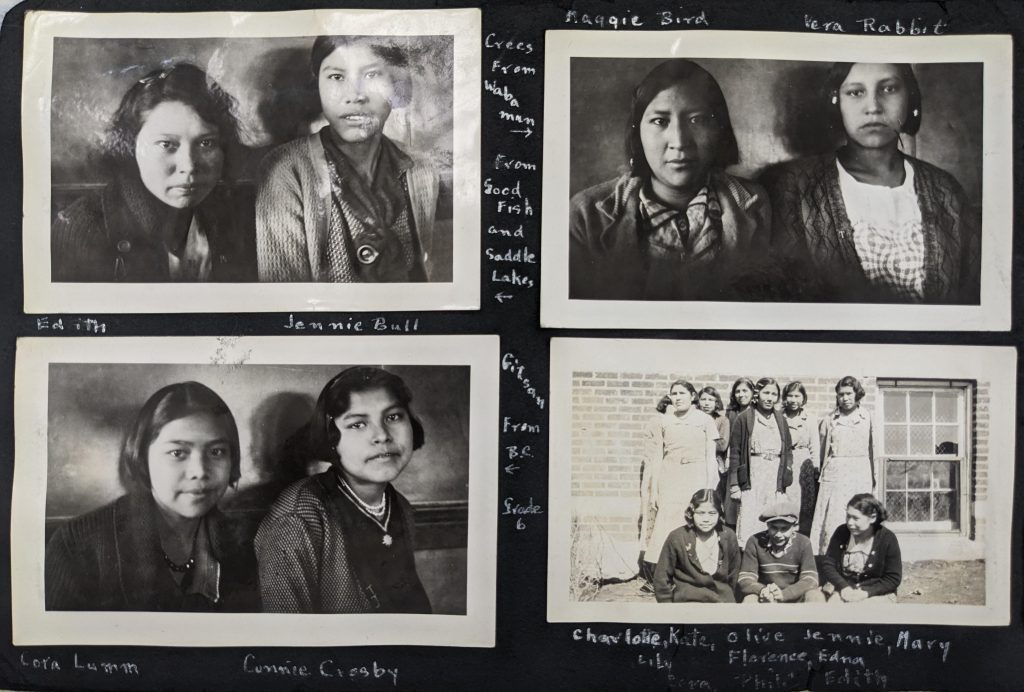

The Department of Indian Affairs was so committed to keeping students in the IRS that when a school with enrolled students needed to close or if a region had more First Nations youth than spaces at their local IRS, students would be shuttled across provinces. EIRS had students registered who came from as far away as Terrace Indian Agency in British Columbia (more than 1,300 kilometres away), and in 1929, the DIA transferred 83 students from an IRS in Brandon, Manitoba (1200 kilometers away) because that school was closed for one year (Edmonton Agency, Vol. 6350, Reel C-8707, 1929).

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

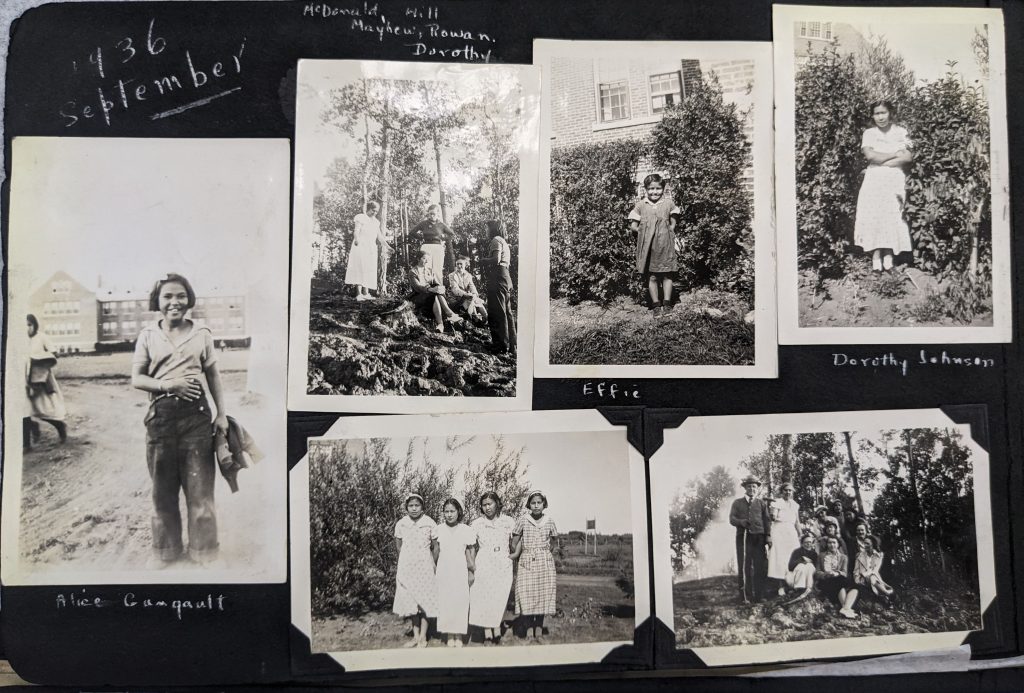

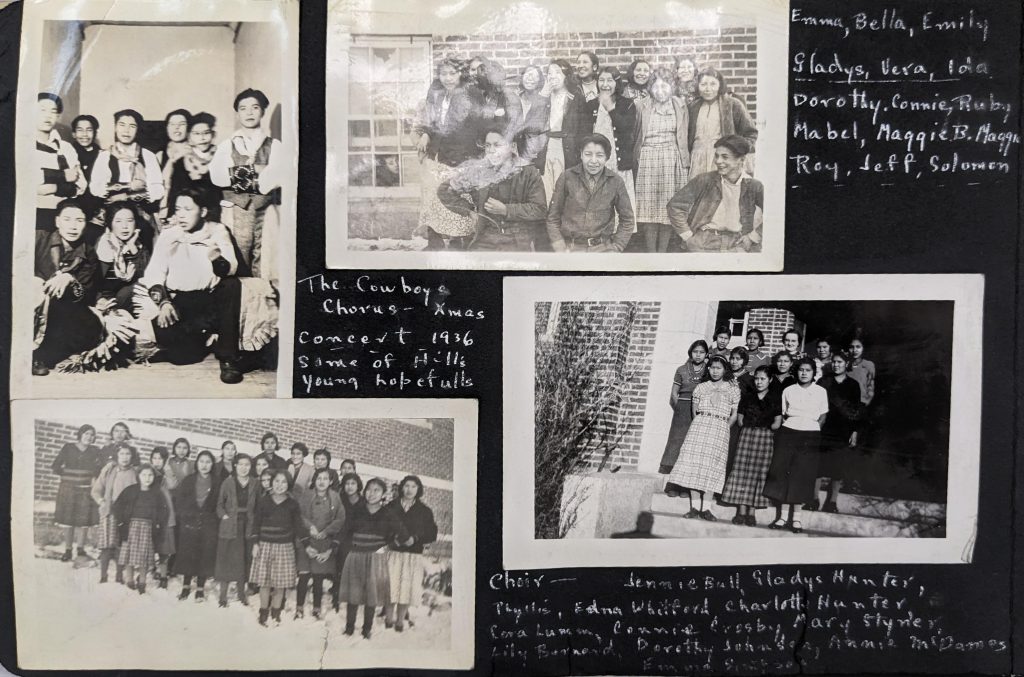

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos related to the third floor of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

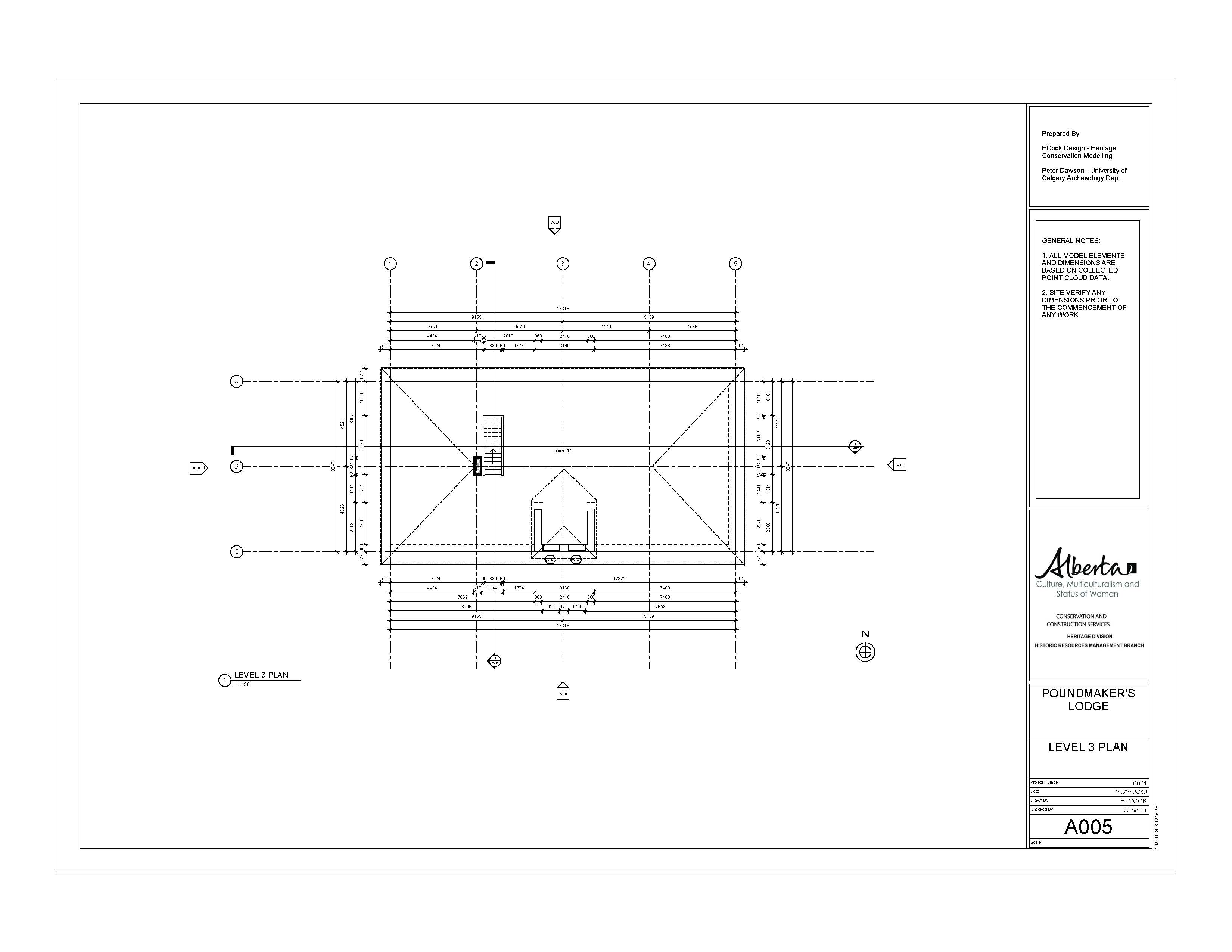

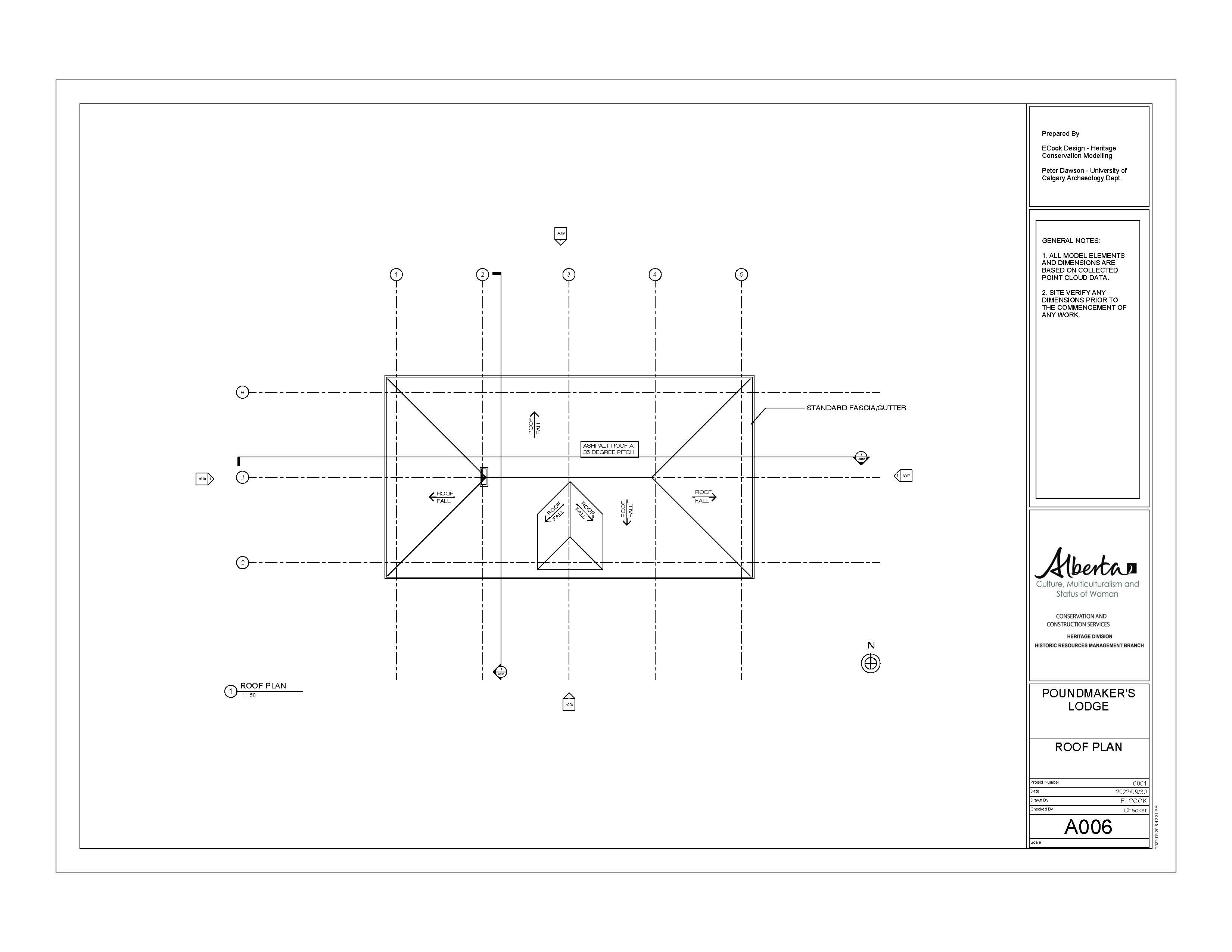

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

When it came dinnertime they hauled us to the bottom basement, that’s where the dinner quarters are. They served us “dinner,” I wouldn’t call it dinner right now. Something we didn’t like, they told you that “you gotta like it.” So what was there- because we’re so hungry even though we had a snack, we’re still hungry– we eat this stuff, I can’t remember what I ate. I know a lot of the diet here, what was here was that, Prem they call it. Prem or now they call Spam, and some potatoes and that was it.

We had our dinner, then it was almost time to bedtime. There was going to be one big meeting after breakfast at 10 o’clock or whatever. It was between the girls’ side, and the boys’ side getting all in one, under one room, still sort of segregated. Go on the same rules. Rules thing again. You know, “no talking to the girls.” Rules with, with girls, I guess. And that was kind of that how we settled what not to do. After that, it was like, I think on a Monday, we were told to “go into these classrooms.”

Even then I didn’t get to see my brother all that time. Maybe they brought him in later or different time or whatever… but it really hurts me to this day that, that four, four months passed, and I didn’t see him. Even though we were in the same dorm, not same dorm, but the same side of the building. I still didn’t see him four months, and that’s what really hurt me.

-Gary Williams

Oral interview with Gary Williams. Conducted by Peter Dawson at Poundmaker’s Lodge, St Albert, May 4, 2022. Transcribed by Erica Van Vugt and Madisen Hvidberg. University of Calgary, Jan 23, 2024.

Image: AB Archives, PR19910383412. Edmonton Indian Residential School, St. Albert, Title: [no names or description provided]. ND.

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more