Carriage House Fourth Floor

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read moreThe Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. The Third Floor is the Most Internally Divided Space in the Carriage House and Includes a Large Classroom. A Mural Depicting a Mountain Range Adorns the Wall on the Other Side of the Classroom and Can Be Seen in the Point Cloud. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud.

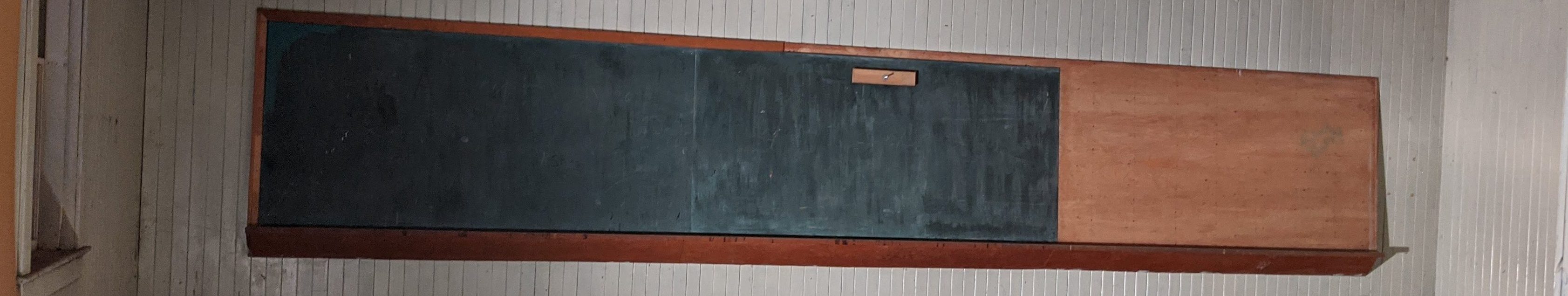

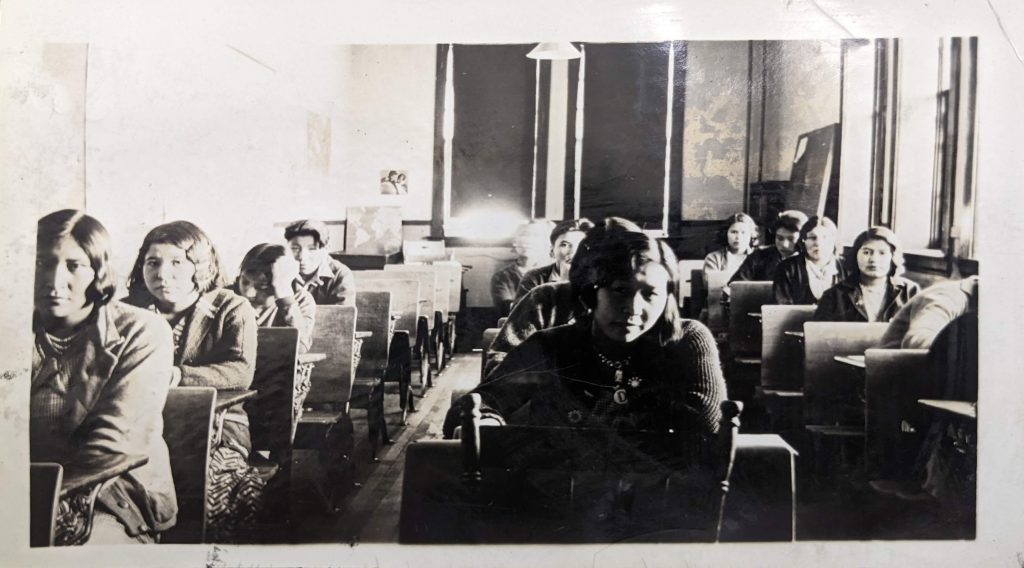

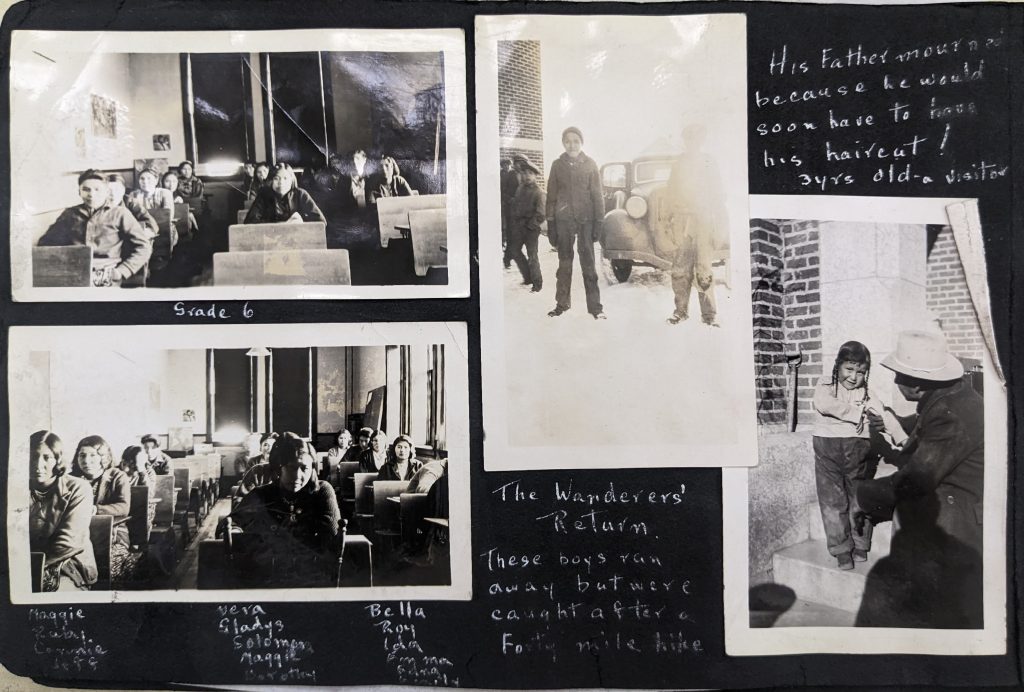

The third floor of the carriage house had a staff room, the coat room for students, and a teaching classroom. Today, this floor most resembles what the carriage house would have looked like when it was last in use; the staff’s quarters still feature a hand painted mural of the mountains; the classroom still has a chalkboard up with some writing from its last use visible; and the coatroom still features numbered hooks for students. When students came to the residential school, they were assigned a number which they would be referred to instead of a name. The students’ clothes from home, upon arrival, would be stuffed into a bag labelled with their number. In the playrooms of the main schoolhouse, there would also be a numbered hook for students’ coats and outside clothes to hang on when they were at the school. Many survivors today still remember the number they were assigned at their schools.

Staff stayed in this building because children lived on the top floor of the carriage house. Students attending residential schools were not given many freedoms and children were constantly supervised or kept under surveillance. Students would often be given severe punishments for any breach in what was deemed by a supervisor to be inappropriate behaviour, including staying up too late, being in the wrong place, and speaking out of turn or in their native languages.

Staffing issues during the war years restricted farming activities at each school, resulting in food shortages that affected the children. Many students attending Blue Quills and Old Sun remarked on the disparity between the meals they received verses those served to staff. Jerry Wood from Saddle Lake First Nation explains:

“we used to walk by the priests’ dining room. You know, they had a nice white table cloth, polished silver, two candles, two bottles of wine with great food while we ate the garbage” (NCTR, Alberta National Event, Edmonton Sharing Circle, 2014).

In addition to malnutrition, issues surrounding kitchen sanitation and unsafe food preparation also placed student health at risk. The repurposing of kitchen equipment, a lack of proper refrigeration, and a failure to enforce basic standards for health and safety were all to blame.

Students often came to residential schools around the age of 5 or 6, but sometimes even younger, and not speaking any English. Yet if they misspoke and tried to communicate in their own language, they would be often by physically punished. William McLean, a survivor who attended the Edmonton IRS starting in 1933, remembers that, “and we were never allowed to speak our own language inside the school building and inside the classroom. If we were caught speaking our language in the school or in the classroom we would get a strapping for it by the teachers or supervisors.”

In extreme circumstances, the students barricaded themselves into spaces together or individually at the school to protect themselves from abuse. Mel Buffalo recounted to the Commission a time when he and other students at EIRS collectively barred the dormitory doors with full dressers to block out the abusers at night [4].

For obvious reasons, the administrative records of the Department of Indian Affairs do not explicitly detail neglect or abuse of the children in the residential school system; however, this is implicit in the way that staffing, the availability of food, punishments, and labour are discussed throughout various documents.

Food insecurity plagued students at all three schools. The excessive expense of staple items like milk was often cited by officials in the Department of Indian Affairs as necessitating the farming of adjacent lands to offset the high costs of food. Such endeavors frequently relied on student labour even though every hour tending crops and livestock represented less time in the classroom. Outside of farming, children were often conscripted for hauling ice and water, constructing outbuildings, moving furniture, as well as performing other menial tasks.

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos related to the third floor of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

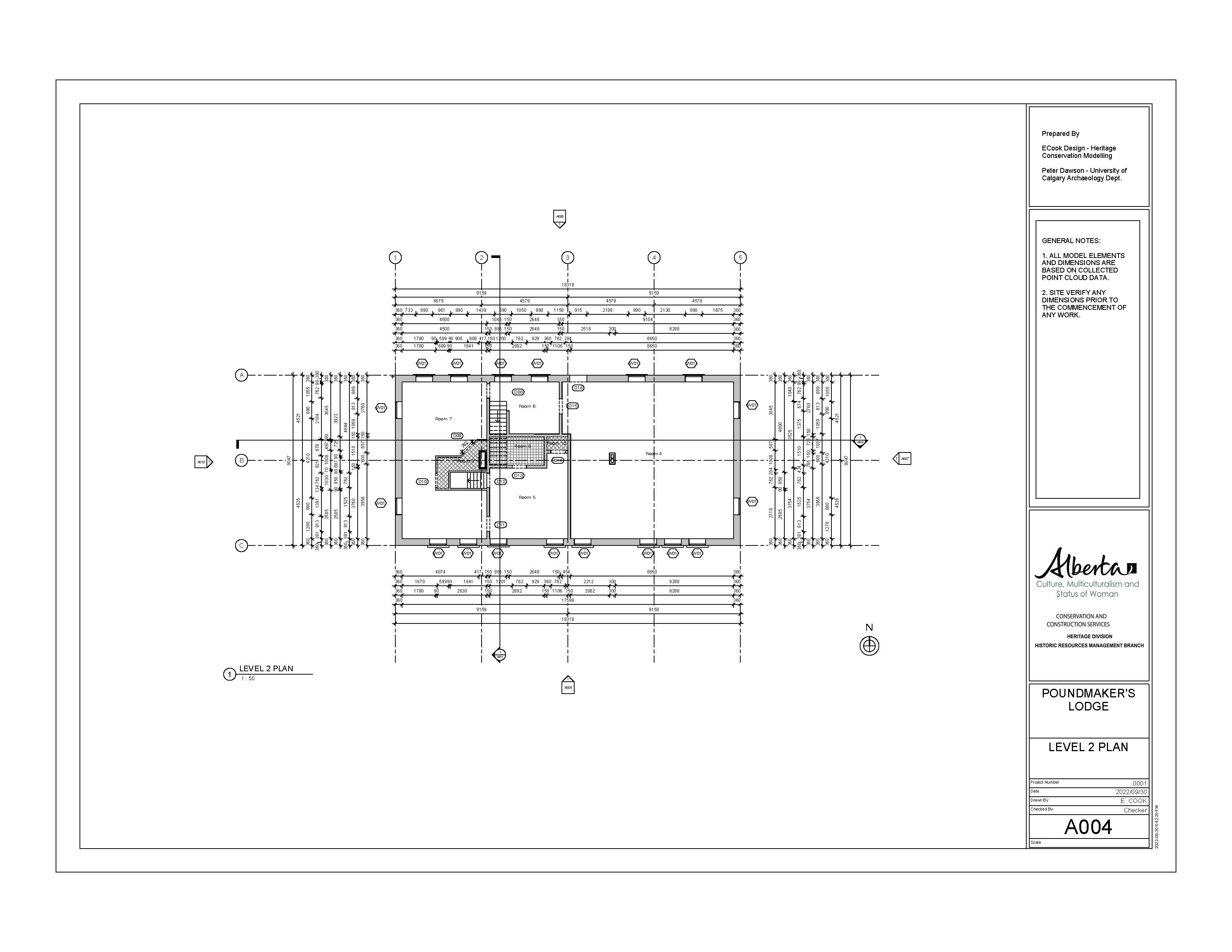

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

When it came dinnertime they hauled us to the bottom basement, that’s where the dinner quarters are. They served us “dinner,” I wouldn’t call it dinner right now. Something we didn’t like, they told you that “you gotta like it.” So what was there- because we’re so hungry even though we had a snack, we’re still hungry– we eat this stuff, I can’t remember what I ate. I know a lot of the diet here, what was here was that, Prem they call it. Prem or now they call Spam, and some potatoes and that was it.

We had our dinner, then it was almost time to bedtime. There was going to be one big meeting after breakfast at 10 o’clock or whatever. It was between the girls’ side, and the boys’ side getting all in one, under one room, still sort of segregated. Go on the same rules. Rules thing again. You know, “no talking to the girls.” Rules with, with girls, I guess. And that was kind of that how we settled what not to do. After that, it was like, I think on a Monday, we were told to “go into these classrooms.”

Even then I didn’t get to see my brother all that time. Maybe they brought him in later or different time or whatever… but it really hurts me to this day that, that four, four months passed, and I didn’t see him. Even though we were in the same dorm, not same dorm, but the same side of the building. I still didn’t see him four months, and that’s what really hurt me.

-Gary Williams

Oral interview with Gary Williams. Conducted by Peter Dawson at Poundmaker’s Lodge, St Albert, May 4, 2022. Transcribed by Erica Van Vugt and Madisen Hvidberg. University of Calgary, Jan 23, 2024.

Image: AB Archives, PR19910383412. Edmonton Indian Residential School, St. Albert, Title: [no names or description provided]. ND.

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read more

The Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more