Carriage House Fourth Floor

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read moreThe Second Floor/Main floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House. This Floor is Presently Used as an Equipment Storage Area by the Alberta Government. It likely Served a Similar Function While Part of the Edmonton Indian Residential School. Click on the triangle to load the point cloud. Labels on the point cloud indicate past room functions.

Now used for storage for Alberta Culture, the first floor of the carriage house used to be used for storing of equipment and supplies for the residential school, such as items used for labour around the grounds which was primarily conducted by students. While education was supposed to be a core goal of the residential school system, children who attended oftentimes spent a lot of their time on vocational “training” and undertaking activities for the running and maintained of the school itself. During the harvest, for example, older boys would often spend their entire day working on the farm [1]

Countless examples of the acceptance of student as labourers are peppered throughout the DIA records. When the DIA agreed to an EIRS request to build a farmer’s cottage in correspondence from May 18,1927, Deputy Superintendent Scott suggested keeping costs low by employing “as much of the school labour as possible” [1,2]

During the harvest, older boys often spent the entire day on the farm, which, by 1929, consisted of 500 acres under cultivation, including 110 acres of wheat, 125 acres of oats, and 40 acres of barley. The potato crop that year produced 3,000 bushels. By 1933, livestock consisted of 15 horses, 59 cattle (both beef and dairy), 135 pigs, 50 chickens and 25 turkeys.

Principal Woodsworth wrote of his students being pulled out of class to haul water into the school during the 10 days in April of 1929 that EIRS was without water, as well as using school labour to build a new shed in preparation for the arrival of additional students from the Brandon IRS [1,2]. Similarly, in preparation for students moving to the new school, Acting Deputy Superintendent General, A.S. Williams wrote in March of 1931 that “staff and older boys” would be responsible for setting up the furniture and supplies [4].

By 1949 it was suggested to the church that students should no longer be used for this kind of labour, but it was not until 1955 that the administration of the Edmonton IRS finally made changes that resulted in more classroom time for students.

The carriage house was used to accommodate students when there was not enough room in the main school building. Overcrowding was a consistent problem in many Indian Residential Schools. The cause appears to be two-fold. First, the per capita grant funding model used by the Department of Indian Affairs was flawed. It assigned a fixed allowance for each student registered. This funding model was the primary source of operational funds, following the construction of a school, and therefore, more students meant more money. Second, churches wanted to recruit and retain students within their denominational faith, a practice that is discussed below. Even with overcrowding, the funds did not leave enough to cover the cost of salaries, basic supplies, or food. Consequently, repairs, maintenance and capital projects were done poorly or not at all.

[1] United Church of Canada. 2022. Edmonton Indian Residential School. The Children Remembered. Electronic document, https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-histories/edmonton/, accessed February 23, 2022.

[2] Ma, K. 2018. The Red Road of Healing. St. Albert Today 13 July. Electronic document, https://www.stalberttoday.ca/local-news/the-red-road-of-healing-1299235, accessed on August 3, 2022.

[3] Poundmaker’s Lodge and Treatment Centre (PLTC). 2022. About. Electronic document, https://poundmakerslodge.ca/about/, accessed August 29, 2022.

[4] Wallace, R. and N. Pietrzykowski. 2022. Digital IRS Archival Research Unpublished report prepared by Collective Heritage Consulting for P. Dawson, University of Calgary. On file in Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

The following virtual tour was created using panospheres from the Z+F 5010X laser scanner. Use your mouse or arrow keys to explore each image. Click on an arrow to "jump" to the next location.

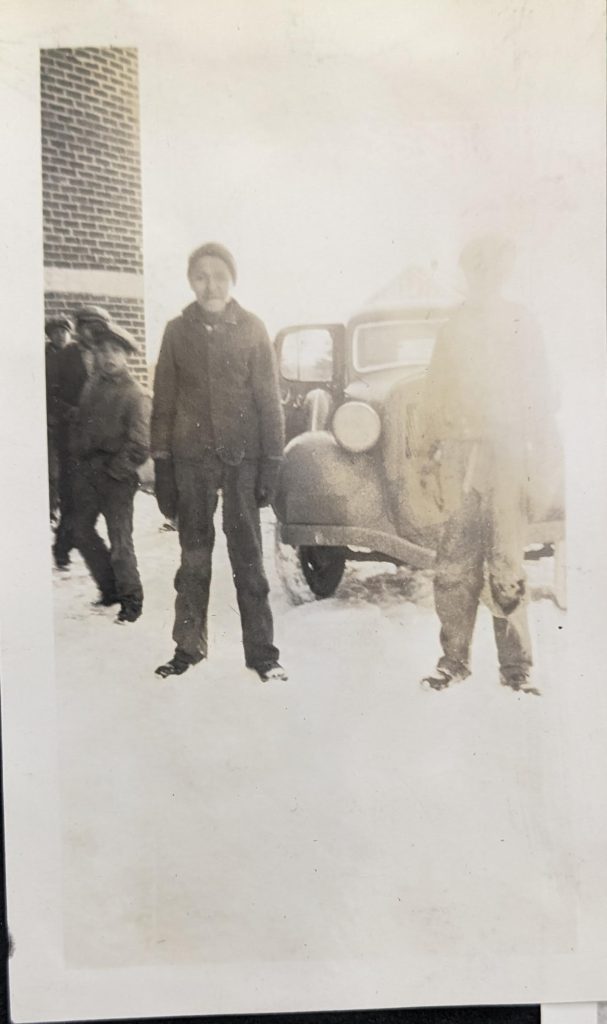

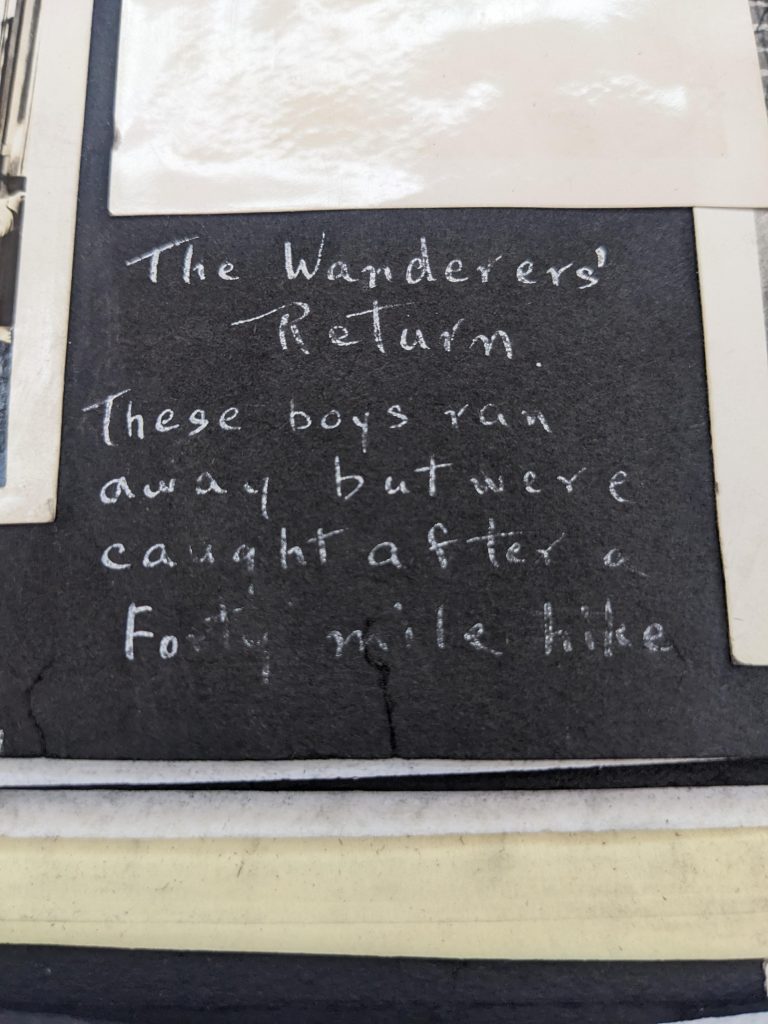

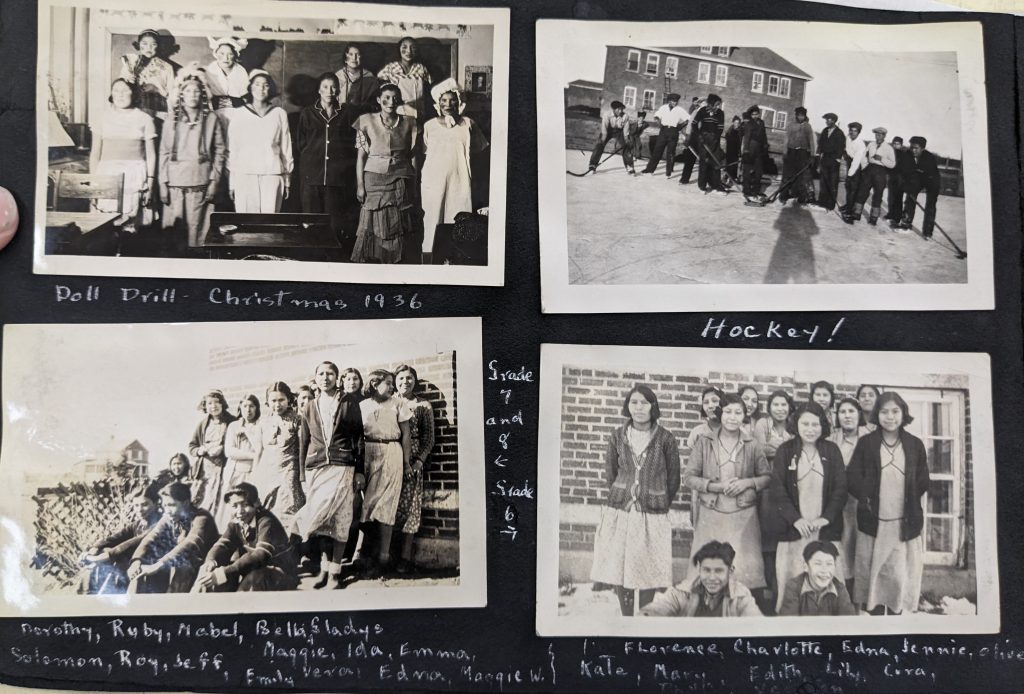

This image gallery shows historic and modern photos related to the first floor of the carriage house. Click on photos to expand and read their captions. If you have photos of the Edmonton IRS that you would like to submit to this archive, please contact us at irsdocumentationproject@gmail.com.

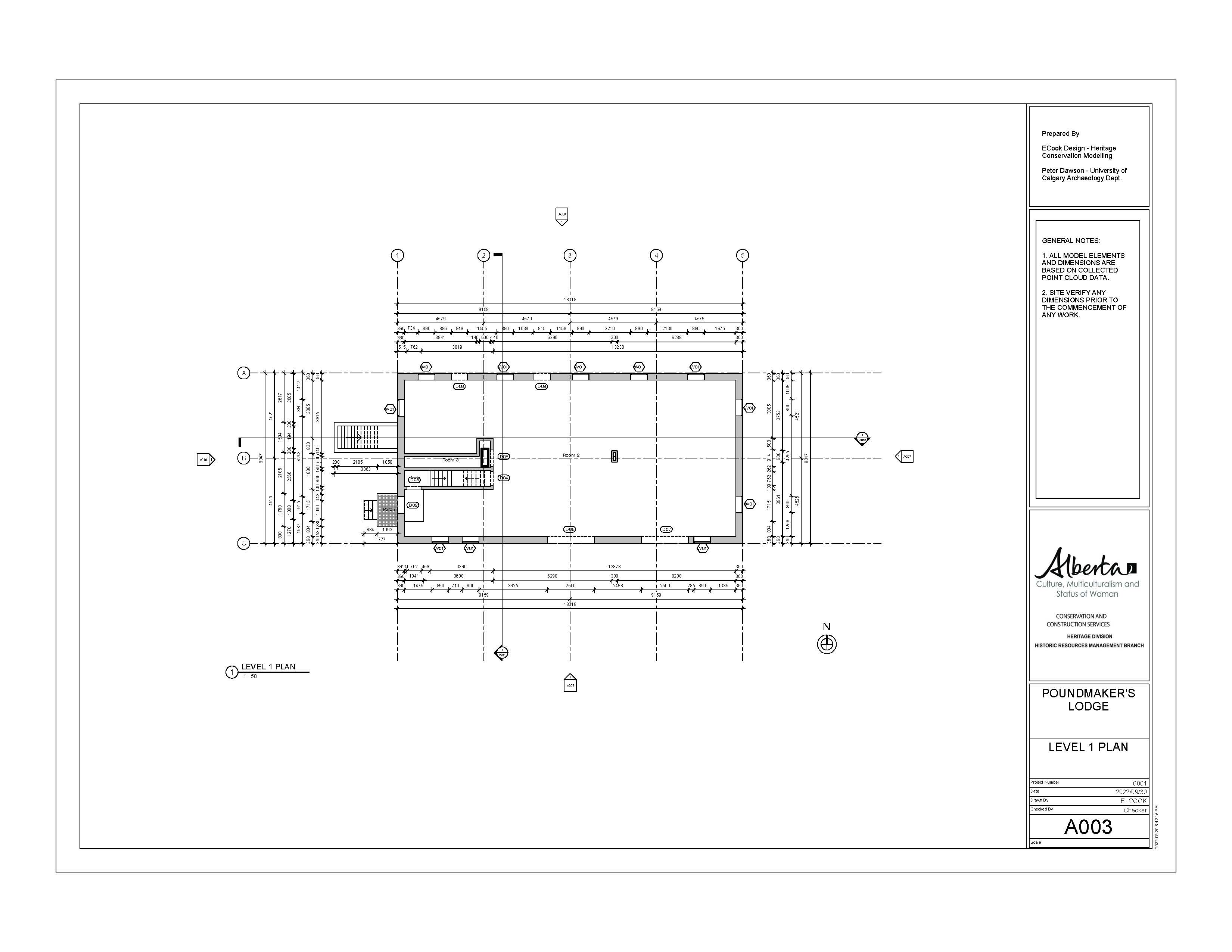

Laser scanning data can be used to create “as built” architectural plans which can support repair and restoration work to The Edmonton Indian Residential School Carriage House. The main school building was lost to fire in 2000. This plan was created using Autodesk Revit and forms part of a larger building information model (BIM) of the school. The Revit drawings and laser scanning data for this school are securely archived with access controlled by Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Center.

We’re from BC. Those of us that are sitting up here and there were many, many, many students from Haida Gwaii to the Gitxsan Nation that went to, that came to Edmonton to go to school here. I suppose we were brought here because the residential schools in British Columbia were full so they started shipping us out.

Our journey started from Prince Rupert, some of us were very, very young, and others were a bit older. We got on a train and this one supervisor that came from here to Edmonton on a train ride. He had boxes and boxes and boxes of lunch with him. In these big cardboard boxes, were our lunches. In this lunch were bologna sandwiches, peanut butter, and maybe an apple or an orange. Three days, he traveled from here to BC. to come and pick us up to be a supervisor on the train on the way back.

You know as well as I do that after three days, Bologna not sitting in a fridge turns green. That’s what was fed to us on a train, green bologna, and some of the children are hungry but I think that most, most of us probably ate just the peanut butter sandwich and got rid of the rest.

Some of us were fortunate enough to have money so whenever the train stopped somewhere, we’d jump off and go to a store if there was one close by. We buy a little bit of goodies and shared with those that didn’t, didn’t have money. The three-day train ride we didn’t have coaches to sleep in, back in those days in the early ‘50s. With the old trains they had these big luggage areas, they were so huge that you could actually climb up there and sleep there. And that’s where a lot of the young people and the older students slept, wherever you could see, we crowded in one, two boxes, two cars- the boys on one car and the girls on the other.

When we got to Edmonton, we were bused there from the train station, or no, actually, I think it might have been from Jasper. We were bused to the residential school. Again boys in one bus, and girls on the other, in another bus.

We got off in front of the school, we looked up at this big building, it was huge, because we were a little then. It was a huge building, you’ve seen pictures out there, and to us it was like we walked in there and we were just literally swallowed up in these buildings.

We got swallowed up and for the girls that’s where we stayed.

– Isabell Muldoe

Notes:

Isabell Muldoe Testimony. SP205_part06. Shared at Alberta National Event (ABNE) Sharing Panel. March 29, 2014. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation holds copyright. https://archives.nctr.ca/SP205_part06

The Fourth Floor/Attic of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carri…

Read more

The Third floor of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage Hou…

Read more

The First Floor/Basement of Poundmaker’s Lodge Car…

Read more

The Exterior of Poundmaker’s Lodge Carriage House….

Read more